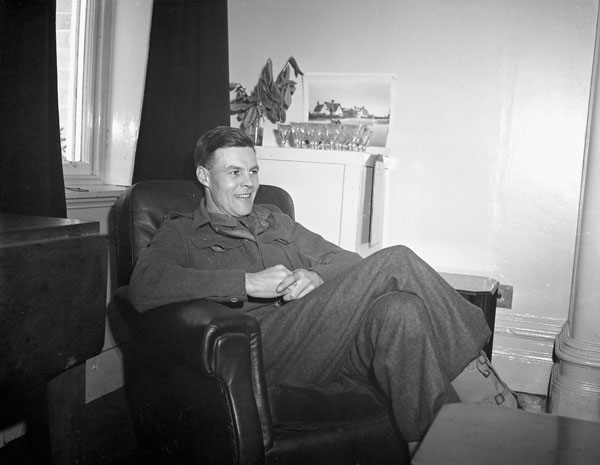

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Merritt, who would one day go on to be a Victoria Cross recipient, spent three years in German captivity. However, by that point he had seen only six hours of combat. Upon finding out that he had been granted the great honor of the Victoria Cross after his release, he described his time as a prisoner of war as “enforced idleness”, adding, “It cannot be translated into virtue.”

Fortunately for Merritt and the history of war, his conduct during his six hours of combat were enough to demonstrate inexplicable gallantry in the face of the enemy. Merritt’s bravery was truly outstanding. During the fighting he charged across an enemy bridge zeroed in by mortars and machine guns. As he charged, he waved his helmet in the air and screamed:

“Come on boys – there’s nothing to it!”

As a Lieutenant Colonel, Merritt would personally cover the withdrawal of his men, leading to his subsequent capture and the end of his time in the war’s active combat. While nearly three years of hard captivity awaited him, he endured without any inkling that he would one day be known as one of Canada’s great war heroes.

A Hero’s Upbringing

Charles Merritt was born in Vancouver British Columbia in 1908. Charles would spend most of his youth growing up without his father who died at the Ypres in the First World War. Despite this tragic loss at an early age, Merritt would settle on having his own experience in the military. He attended the Royal Military College of Canada where he graduated with honors. He would go on to receive a commission with the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada in 1929. He went on to practice law in Vancouver until his unit was mobilized at the beginning of the war in 1939.

Given the rank of Major, he shipped out to England where he would spend the next two year’s training for the day he would lead men into combat. Promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1942, he was given command of the South Saskatchewan Regiment as they awaited a rendezvous with history at the famed Dieppe raid.

The raid at Dieppe was an attempt to test and prove that an invasion of continental Europe was possible. They would also use the raid to destroy enemy gun positions, collect intelligence, and give the Allies a much needed victory. Unfortunately for the Allies, they would indeed learn hard lessons about an invasion, but they would learn out of what could only be described as an unmitigated disaster.

Gallantry in a Failed Raid

As Merritt’s Regiment approached under the cover of darkness, he was set to be one of the first allied soldiers to set foot in conquered Europe for quite some time. In keeping with the theme of the Dieppe raid, almost nothing went right as the majority of the regiment landed on the wrong side of the river Scie estuary. As a result, Merritt and the bulk of his men would be forced to cross a narrow bridge after landing in order to reach their objectives. However, by this time the element of surprise was long gone and the Germans had the bridge zeroed in with whatever machine guns and mortars they could bring to bear.

The first wave across the bridge was wildly unsuccessful leading in mass casualties strewn about the bridge. Meanwhile, the only company of Merritt’s regiment to land on the right side of the river had reached their objective and sent what would become for the entire invasion force one of only two success signals ever sent.

Realizing that time was of the essence and his men were without proper combat experience and in need of a spark, he set out across the bridge alone. Wildly waving his helmet in the air, he shouted, “Come on boys – there’s nothing to it!” and rushed forward. Lt. Col Merritt took the enemy by surprise with his audacity and made it across the bridge along with a contingent of his men.

Inspired by his leadership, additional men poured across many using the bridge’s rafters as cover. With the majority of his surviving men across, Merritt looked to press the attack but was hindered by a lack of available ammunition and communication with the destroyers off the coast for additional fire support.

Despite his best efforts, the Dieppe raid had left him with less than a battalion of 300 fighting men and no hope of securing their objectives. He took his men and established a modified perimeter in order to hold out against the counterattack from a numerically superior enemy. Just a few hours into the war, Merritt would be as far into Europe as he would ever go with a rifle in his hand.

A Short War

When the order was given to retreat back to the beaches for withdrawal, Lt. Col Merritt led the rear guard personally in order to ensure the exit of as many of his men as possible. As the ammunition ran out and the enemy closed in with heavy arms, Merritt and other Allied forces were forced to surrender in an effort to cover the continued retreat of the main force. Over a decade of military training and it would take but 6 hours for Merritt’s war to come to an end. This was a tough pill for him to swallow, but he took solace in the fact that he helped many men escape for home.

He was initially taken to a prison camp in Bavaria where he would help lead an escape attempt of 64 men through a 120 ft tunnel. After a massive manhunt, they were eventually captured and he was sent to the “escape proof” POW camp at Colditz Castle. There he would remain until his release in 1945. It was upon his release that he was informed of his Victoria Cross.

He would eventually return to Canada a national hero and go on to serve as a Member of Parliament. However, if you were to ask Merritt what he wanted to achieve he would have told you that it was to see what he had accomplished for his country had he been able to serve more than 6 hours in combat.

Meanwhile, the rest of Canada and the Allies would argue he had served enough to prove he was worthy of the highest military honor.