US Coast Guard Cutter Comanche left Boston in January 1943. She made contact with her convoy on the 29th and proceeded as scheduled. It was a routine escort, three troopships, and three Coast Guard cutters. They sailed into the frigid waters of the North Atlantic, hoping and praying they would return home again.

They were following Convoy Route “SG,” from St. John’s, Newfoundland, to Greenland. They knew these waters well, but the men on board were cautious, two ships had been sunk on this patrol just five months ago. Despite the possible danger, they knew these troopships needed to continue their journey. The men on board were required in Europe, to help win the war so they could all finally get back home.

The first three days of escort went smoothly. They made it past the site where the two ships had been sunk and steamed calmly into the North Atlantic. The cold air made life above deck almost unbearable, with the wind, snow, and ocean spray whipping around. The men huddled down below, hoping their thin steel walls would keep the cold seas out.

At 0102 on the 3rd of February, going into the fourth day of their voyage, the watch spotted a white flash from the steamer Dorchester. The general alarm echoed through the Comanche. Her crew jumped out of bed and sprinted to their posts. Dorchester’s lights began flashing, and the ship began to sink.

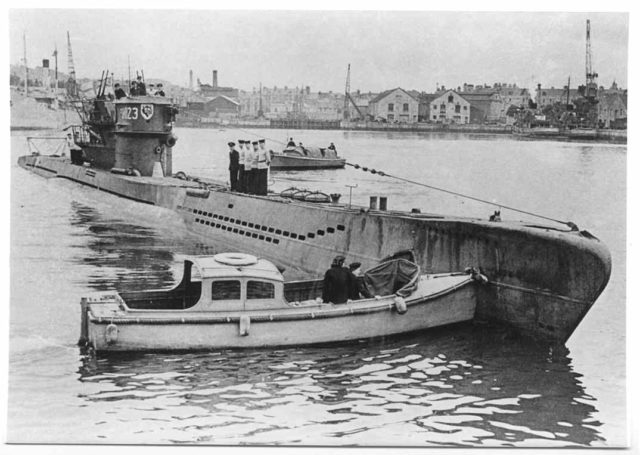

By 0112 Comanche had moved to intercept the submarine whose torpedo had just found its mark. However, it was to no avail as the deadly attacker had submerged, hiding in the murky waters of the North Atlantic. The Dorchester sank 8 minutes later.

For the next hour Comanche searched for any sign of the submarine, but at 0226 was recalled to aid the survivors of the Dorchester. The operation took on an even more urgent need. The Dorchester had 904 men on board, who had been thrown into the cold ocean. Comanche found lifeboats full of barely conscious people, who had to be helped on board by the Comanche’s crew. They also found men still alive, floating in their life jackets, hypothermic, and almost completely paralyzed by the cold.

Three officers and nine enlisted crew from Comanche went over the side of their ship, plunging into the frigid waters to pull out survivors. This was a new technique but had already been proven effective, especially when the men were too numb to climb aboard themselves.

The Coastguardsmen had rescued a total of 97 men that night when a call went out around the ship: their Executive Officer, Lieutenant Anderson was still in the water, and unresponsive. He was floating limp in his lifejacket, and everyone on board knew he had only a short amount of time before he would die.

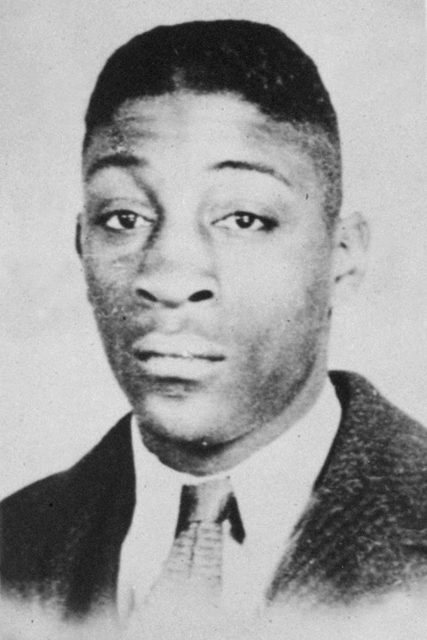

The Steward’s Mate, 1st Class Charles W. David Jr., who had just spent what probably felt like an eternity rescuing survivors from the Dorchester, volunteered to jump back in. He dove off the side of the ship, with nothing more than a lifeline around his waist to protect him. Fighting the rough seas and extreme cold he made it out to the Lieutenant and brought him back to the ship, where others were able to haul him on board.

David succumbed to hypothermia and collapsed on deck. His shipmates rushed him down to the medics bay, where he was wrapped in fresh clothes and warm blankets. Despite these measures StM1c, Charles W. David Jr. passed away two months later, after a desperate fight against pneumonia.

For his actions, he was posthumously awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, given to his widow, and young son. His sacrifice of self to save the lives of others exemplifies the ideals of the United States Coast Guard. In further recognition of this, USCGC Charles David Jr. was commissioned on November 13th, 2013, 70 years and ten days after that tragic night off Greenland’s coast.