The closing of the Falaise gap was one of the most dramatic moments in the Second World War. Allied troops cut off a large part of the German army, removing it from the conflict. It was a remarkable achievement, sealed by the efforts of Polish and Canadian troops. But ever since, a question has hung over this operation – could more have been achieved?

The Falaise Pocket

Following the D-Day landings in June 1944, German forces tried to contain the Allies in a beachhead against the Normandy coast. Weeks of fierce fighting ensued, with Allied troops slowly pushing back their opponents.

In late July, the situation changed. On the western flank, the Americans launched Operation Cobra. This smashed a hole in the German lines, through which an armored column poured. American forces swept south and east, getting into the Germans’ rear.

As that American advance turned back north, a large force of Germans became contained in a pocket of ground west of the town of Falaise. Tens of thousands of soldiers, many retreating from the Allied offensives, were crammed together in a shrinking space.

Operation Totalize

The Allied commanders realized that they had been presented with a huge opportunity. The Germans were surrounded on three sides. If the Allies could complete this encirclement, then all the Germans in the Falaise pocket would be forced to surrender.

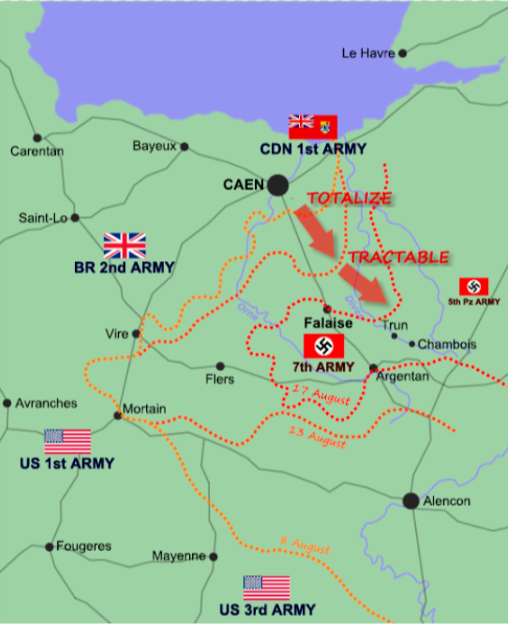

The first attempt to cut off the Germans was Operation Totalize, launched by II Canadian Corps on the night of the 7th of August. Following a swift and effective aerial bombardment, Canadian, British, and Polish troops advanced out of the north towards Falaise.

At first, Totalize seemed to go well. A night attack by mobile troops led to significant advances against vulnerable German forces.

But the Germans, many of them fanatical SS troopers, swiftly pulled together. Their 88mm guns, one of the most effective weapons in Normandy, took a toll on Allied armor. Canadian morale wavered, undermined by the inconsistency of their leaders, who varied from highly effective to what the official Canadian historian referred to as “not fully competent”.

By the 11th of August, the advance had ground to a halt, still a dozen miles from Falaise. Totalize drew to a close.

Operation Tractable

The more time passed, the more of the Germans might slip out to continue the war elsewhere. The Americans were impatient to get the job done but faced their own internal divisions. General Patton wanted to ride in and close the pocket in a pincer movement. Bradley overrode him, conserving resources.

And so, on the 14th of August, another offensive was launched by the First Canadian Army, a force which included Polish troops. This time, the Canadians used smoke instead of the night to conceal their advance. They again used tactical bombing to disrupt German formations as the ground troops moved in.

From early on, Operation Tractable was beset by problems. The Laison River proved harder to cross than expected, slowing the advance. A failure of communication between army and air force led to ground units using yellow smoke to identify themselves while pilots were using it to mark targets, leading Allied planes to attack their own side. The Germans continued to use the terrain and their superior equipment to their advantage, making the Allies pay in blood for every step forward.

Despite these setbacks, Tractable increased the pressure on the Germans. By the end of the 15th, the Canadians were a mile from the edge of Falaise, while Canadian and Polish divisions were pushing south around Trun.

Only a narrow gap separated the Canadian Army in the north from the Americans in the south.

Closing the Gap

The writing was on the wall for the Germans west of Falaise. They began efforts in earnest to escape through the gap so that they could continue the war further east. Field Marshal von Kluge ordered a retreat, for which he was relieved of command by an enraged Hitler, who was unwilling to accept the reality of their difficulties.

As Germans streamed through the gap, Allied planes rained carnage down upon them, trying to destroy as many of these easy targets as they could.

Meanwhile, the Poles and Canadians were ordered to close the gap. Their experiences with friendly fire made them even more cautious of advancing with so many planes in the air. They faced counter-attacks from SS forces and continuing resistance from those Germans fighting to keep the gap open. It took until the 19th for the Poles to link up with the Americans at Chambois. Even then, the gap was not yet sealed, as Germans were still fighting their way past hills held by Canadian and Polish forces.

At last, on the evening of the 21st, the Poles and Canadians linked their formations into a complete line, cutting off the gap. The Germans still in the pocket were completely surrounded. The survivors soon surrendered and the tide of war moved east.

Great Achievement or Missed Opportunity?

The Germans lost an estimated 60,000 men in the Falaise pocket – 10,000 dead and 50,000 captured. Hundreds of tanks and assault guns were taken. It was a huge victory for the Allies.

On the other hand, 20-50,000 Germans had escaped from the pocket while the Allies struggled to close the gap. Many historians have criticized the generals for not completing the encirclement sooner. If Montgomery had thrown more British forces behind the faltering Canadians or Bradley had risked American troops in a push north, could they have achieved even more?

Closing the Falaise gap faster would have meant greater losses for the Allies, particularly the Poles and Canadians who bore the brunt of the fighting. If it had inflicted more casualties than it cost, it might have been worth the price. But so much uncertainty hangs over the numbers that this is impossible to calculate.

For the men who fought in the gap, it was a great achievement, and a relief when the fighting was done.