During the Second World War, Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) reinvented the art of covert warfare.

The organization recruited, trained, and equipped both secret agents and commandos, launched daring missions against enemy targets, and maintained intelligence networks across Europe for nearly the whole length of the war.

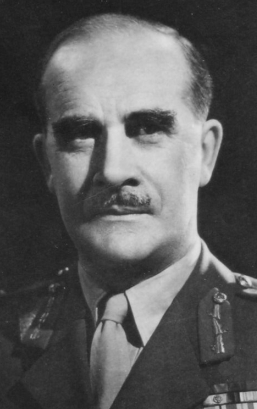

The man who did the most to shape these operations was Colin Gubbins.

The Impeccable Scotsman

Gubbins was a distinctive and sometimes intimidating figure. A short, impeccably dressed Scotsman with neatly kept hair and mustache, his penetrating gaze made some acquaintances uneasy while reassuring others of the strength of his character.

His was the sort of mind that Britain badly needed to lead its covert operations. Military intelligence had been neglected between the wars, and covert warfare was frowned upon as an ungentlemanly activity.

But Gubbins had the strength of character to cut through such concerns. Behind his soft speech lay a personality of determination, efficiency, energy, and imagination. He was the sort of man who could deliver unconventional solutions.

Background and Early Career

Gubbins was born in 1897 in Tokyo, where his father was working. Sent home to Scotland at an early age, he was raised by puritanical aunts who encouraged toughness of character and discouraged such frivolous pastimes as games and laughter.

At the age of sixteen, young Colin moved from one sort of discipline to another when he joined the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. There, he gained an image for recklessness and determination.

Commissioned into the artillery, Gubbins spent most of the First World War on the Western Front. He was repeatedly wounded, including being shot through the neck. He was awarded the Military Cross after digging comrades out of the mud under fire following a German artillery attack.

While many of his comrades left the military after the armistice, Gubbins stayed on. He served in Russia, India, and Ireland, seeing the new reality of irregular warfare, before becoming a desk officer in military intelligence.

The Start of the Other War

In the spring of 1939, with war clouds gathering over Europe, Gubbins was recruited to the small group of officers planning to fight Nazi Germany by covert means.

He started out by writing guides on irregular warfare, based on research and his own experiences. He drew on such diverse sources as Lawrence of Arabia, Sinn Fein, and Al Capone to create an instruction manual unlike any that had gone before. It covered such practical topics as blowing up transport links and poisoning enemy water supplies.

In the early days, Gubbins and his operatives always seemed to arrive just too late. They were on their way to Poland when the Germans invaded and so did little to help fend off the Nazis.

Sent to Norway as part of the British force there, they spent the short campaign on the retreat, damaging transport links ahead of the Germans, before being evacuated with the rest of the British expedition.

SOE

In the summer of 1940, the government amalgamated several covert organizations into a single department – the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Gubbins was made Director of Operations and in this role became the most important figure in shaping Britain’s covert operations.

In September 1943, he became director of the entire organization. By then, he had reached the rank of major-general, in recognition of his impressive service.

The SOE existed to fulfill Winston Churchill’s dream of setting Europe ablaze, making life impossible for the Nazi occupiers. But its work would eventually go beyond this.

Burning Through Europe

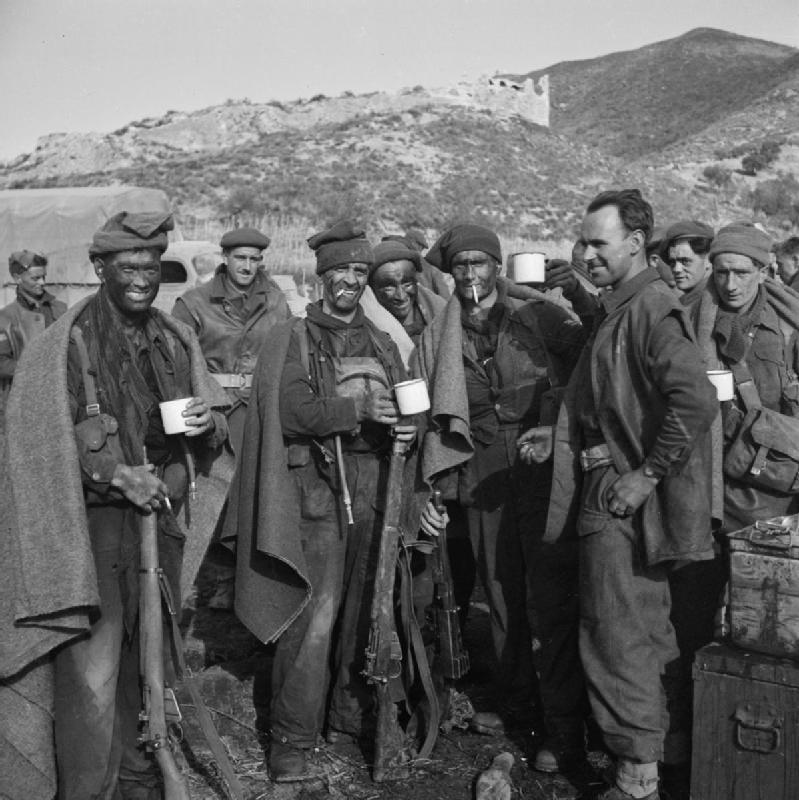

The work of the SOE in Europe was some of the most remarkable of the Second World War.

From the start, the SOE supported resistance movements across the continent. They encouraged the growth of the French Resistance, equipping them with both radios and weapons.

In Greece, they joined partisans in destroying transport links. In Poland, Gubbins’ old contacts helped them establish vital intelligence networks.

They also organized direct attacks by commando units of British and Allied soldiers. These included the sinking of German ships in harbors and the destruction of a Norwegian hydroelectric plant vital to atomic weapons research.

Weapons and Training

The SOE prepared its agents through a unique program of training and weapons design. Gubbins oversaw the specialist facilities for both these activities, recruiting remarkable and unconventional minds to ensure success.

He was willing to look beyond the military establishment and recruited colonial policemen, inventors, and journalists. He was concerned not with connections or careers but with skills and experience.

The results were amazing. Men and women trained to hide behind German lines, to precisely place explosives, and to kill with their bare hands. Weapons ranging from limpet mines to anti-tank missiles to the specialist grenade that killed the brutal Nazi commander of Czechoslovakia, Reinhard Heydrich.

The Wider World

Gubbins commissioned operations that reached beyond Europe. On one occasion, he sent commandos to act as pirates off the coast of West Africa, stealing three German ships from a Spanish colonial port without anyone knowing who was behind it.

On another occasion, operatives in Greece stalled the flow of Axis supplies to the vital fighting in North Africa.

When America entered the war, it learned many lessons from the British example. The techniques Gubbins had developed were carried over into operations against the Japanese in Asia.

War’s End

By the end of the Second World War, Gubbins had created a slickly running machine of which he was immensely proud. But there was no place for the SOE in the post-war world. The executive was shut down.

With its closure, Gubbins finally left the military life after more than 30 years.

Civilian life didn’t suit Gubbins. He worked for a rubber company and then a textile firm, but found neither rewarding after the thrill of running a covert war.

Instead, he found satisfaction in founding the Special Forces Club in London where he kept in contact with old colleagues and, in the belated recognition his work could openly receive at last, with accolades from leaders around the world.

He died in February 1976 in the Outer Hebrides, where he had retired with his second wife, Anna.