In December 1941, Japan invaded the Philippines. American forces there carried out a fighting retreat. Holding out as long as they could, they retreated into the Bataan Peninsula. Then after four months of fighting, the last troops in Bataan were forced to surrender on April 10, 1942.

All that remained was the island of Corregidor.

An Island Fortress

Corregidor is an island at the mouth of Manila Bay. Shaped like a tadpole, its geography is dominated by three hills – Malinta Hill, Middleside, and Topside.

The whole area was set up to serve the batteries of coastal artillery with which it dominated the approach to Manila Bay. There were docks, warehouses, barracks, a power station, a hospital, and even a recreational club.

Topside, the steepest hill, dominates the tadpole’s head. It contained over 50 artillery pieces, ranging from three to twelve inches in diameter. Mines and anti-aircraft guns helped to protect the batteries.

At the start of May 1942, 11,000 troops were on the island.

Under Siege

The first Japanese attack on Corregidor was a bombing run on December 29, 1942. With most of the fighting previously contained to the mainland, it was a surprise to the troops on the island.

Bombing continued until the middle of January when the attacks stopped. In early February, it was replaced by shell fire from enemy artillery.

Shelling was a grimmer prospect than the bomb attacks. The sound of approaching bombers could be heard from a long way off. It gave troops on the island time to take cover before the bombs fell. The weather limited the bombing – pilots preferred to fly in good conditions, and there was little preventing them from doing so. Night time and rain provided a relatively safe time to walk around the island.

The shelling was different. The whistle of incoming fire could be heard only seconds before it hit. The bombardment continued regardless of day or night or what the weather was doing.

Life under siege was harder for some troops than others. Most of the infantry had packed themselves into Malinta Tunnel, giving them strong protection from the explosions. The Marines, barracked on the surface, had a tougher time. They dug caves and shoveled dirt into the walls of Middleside Barracks in the hope of better protection.

Meanwhile, the flaws in the island’s defenses were starting to show. Some guns sat in emplacements that were exposed to the sky and so were easily hit by bombers. Others, mounted to point out to sea, could not be turned to return fire against the Japanese artillery. Also, the power plant lay in an exposed position.

The Japanese bombers took heavy casualties from the anti-aircraft batteries, but it did not stop them doing their work. Almost all the shore guns were destroyed.

The need to be prepared for an invasion meant not everyone could stay safely under shelter. Men stood watch, looking out across the sea, ready to raise the alarm. Troops were prepared at all times in case an invasion occurred.

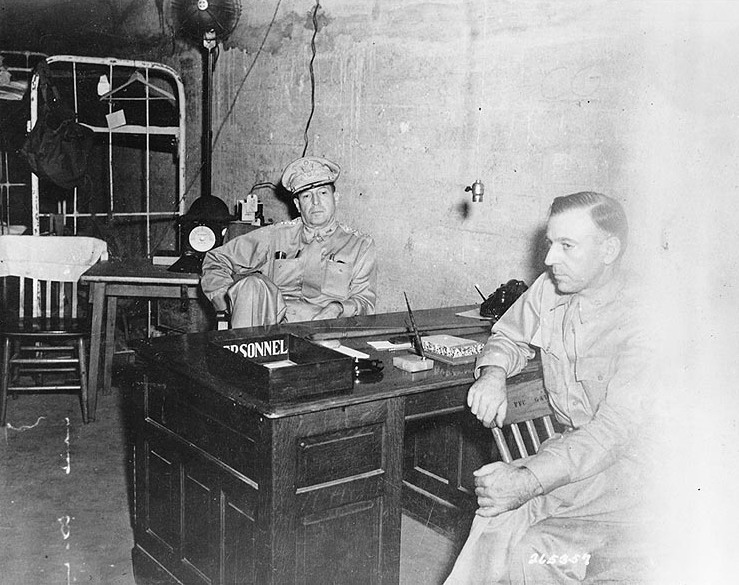

General MacArthur had promised that help was on its way from the United States. As the weeks passed and no support came, the situation looked increasingly bleak. When MacArthur left the Philippines to create a new headquarters in Australia, it was a sensible move. It was also a sign to the troops on the island they were in real trouble.

In early April, the defense of Bataan collapsed. Those on Corregidor saw men in boats desperately trying to reach them, under fire from Japanese artillery. Only a few hundred made it.

The Assault

On May 1, a heavy bombardment was launched. Around 16,000 shells fell in 24 hours. On the 2nd, the Japanese hit the magazine of Battery Geary, one of the few left on the island. The ammunition explosion shook the whole of Corregidor.

The main assault on the island was approaching.

On the night of May 5, two battalions of Japanese infantry sailed for the island. Strong currents made it difficult for them to land in the right place and bring their equipment onto the shore.

One Japanese force landed on beaches between North Point and Calvary Point. They faced stiff opposition but managed to drive back the defenders and establish a beachhead.

The second Japanese formation faced the toughest opposition in the form of the 4th Marines Regiment and their strong defensive positions. The Japanese remained trapped in their landing zone, and most of their officers were killed. A few Japanese soldiers linked up with the first force, but many remained stuck and under fire.

As the Japanese moved inland, fierce fighting broke out around Denver Battery. Snipers, grenades, and brutal close combat all played an important part.

Japanese reinforcements trickled into the landing zone. Around 09:30 in the morning, three tanks arrived. The men from Denver Battery retreated to the mouth of Malinta Tunnel just as a massive artillery barrage struck.

Surrender

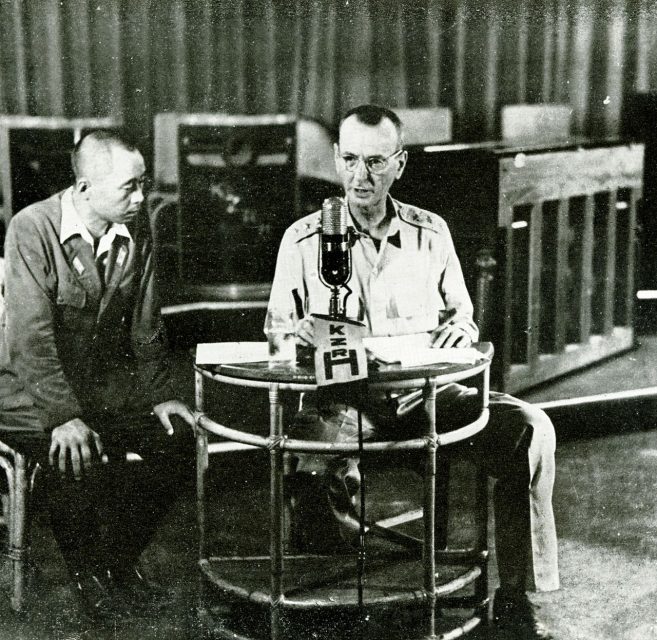

The Americans had nowhere left to go. The American Lieutenant General Wainwright weighed up the situation and realized surrender was the only option. He could perhaps have held out for one more day, but it would be at the cost of thousands of lives and bring little benefit.

On the afternoon of May 6, less than 24 hours after the Japanese landings started, he sent two officers with a white flag to talk terms.

The Americans burned flags and broke ceremonial swords rather than let them fall into enemy hands. They disabled their weapons. Then they surrendered to the Japanese.

800 Americans and Filipinos had died defending the island. 11,000 more were in captivity and would spend the remainder of the war suffering horrendous conditions on Japanese prison boats or in labor camps. The Philippines had fallen.

The courage of those men would not be forgotten. As Wainwright’s troops became POWs, MacArthur was preparing for the fight that would eventually bring American forces back to Corregidor.

Sources:

Hugh Ambrose (2010), The Pacific