The hot Tunisian sun beat down on the steel of tanks and armoured personnel carriers, planes strafed the artillery positions and the tracks of tanks churned the ground to mud or filled the air with clouds of choking dust.From dawn until dusk on the 6th of March, 1943, the Axis armies of Nazi Germany and her allies in North Africa hammered against an impenetrable wall of allied artillery fire.

The Axis forces were, by now, poorly supplied. Food was scarce, fuel was in short supply and the lack of water was a constant torment. They had been engaged in a creeping retreat for months as the allies pushed them back toward the Mareth line. This was a line of forts and bunkers which had been built by the French before the outbreak of World War Two.

It now formed a key position for the Axis forces, whose engineers had reinforced it further, creating a tortuous network of barbed wire, concrete walls, machine gun nests and infantry bunkers. There were anti-tank and anti-aircraft emplacements, and minefields containing hundreds of thousands of anti-tank and anti-personnel mines. The Mareth line stretched for miles, from the coast of the Mediterranean in the North-East to the Matmata hills at the South-West.

South of the line lay the city of Medenine, occupied by the Allies. Around the city, facing the Mareth line, but still some distance away stretched the Allied positions. The Allied commanders knew that the Mareth line would have to be taken if the combined Axis powers of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy were to be driven out of the North African theatre once and for all. To this end, and following intercepted communications indicating that a counter-attack was imminent, the Allied positions had been heavily reinforced. They now comfortably outnumbered the enemy armour, and they sat tight, awaiting the Axis attempt to pre-empt the inevitable assault on the Mareth line.

When the blow fell, it was not without warning. The top secret code-breaking operation at Bletchley Park in England had intercepted and decoded communications which allowed the Allies to anticipate their enemy’s plans. At 5.36 am on the morning on March 6th, the code-breakers informed the British General Montgomery that the attack was about to begin.

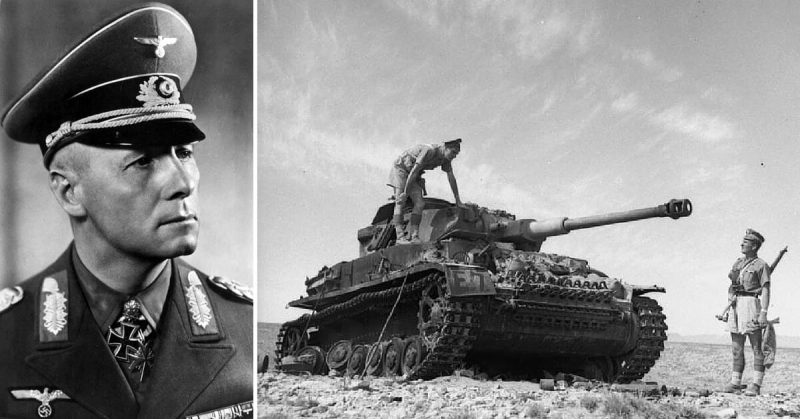

Montgomery was in charge of the Allied forces in North Africa at the time. The Axis army – called the ‘army group Africa’- was under the command of the infamous Erwin Rommel. Again and again, these two men had faced each other in the North African theatre of World War Two, and time and again Montgomery’s command had prevailed.

Across the rest of the world, too, the forces of Nazi Germany and her allies were losing ground. February of 1943 had seen the surrender of what remained of the German 6th army, after the prolonged and bloody campaign against Stalingrad.

The United States had entered the conflict and was fighting hard against the Japanese far to the East. Allied bombers were carrying out raids on Berlin, and Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, was discussing plans for an eventual full-scale invasion of Nazi-occupied territory in Europe, with the American President Franklin Roosevelt.

The landscape was swathed in a thick, cold sea mist when the attack on the Allied lines around Medenine began. Under cover of the fog, mobile field artillery units advanced into range all along the line. These were small, fast moving gun platforms mounted on wheels or tracks and delivering an impressive weight of fire for their size.

They opened up against the Allied positions while heavy tanks from the 15th Panzer division rumbled forward from their positions in the foothills to the south of the Mareth line.

In the fog, a unit of Allied Bren carriers – small armoured vehicles armed with light machine guns and 2-inch mortars – stumbled upon a column of track mounted anti-tank guns and several trucks of infantry. There was a short, sharp engagement, but the Axis vehicles were taken by surprise. The Bren guns roared. The gun crews scrambled to bring their weapons to bear and return fire, the truck mounted infantry were thrown from their vehicles and pinned under a hail of machine gun fire.

One Bren carrier crumpled under a direct hit. A wall of sound filled the air as the few surviving attackers withdrew, but the Bren gunners did not pursue. On all sides could be heard scattered bursts of gunfire punctuating the deeper explosions from the attacking field artillery. As the sun rose higher the fog began to clear, and the Bren gunners returned to their line.

Now the attack could be clearly seen. All along the great curve of the defences around Medenine, men looked out and saw columns of tanks approaching, screening trucks packed with infantry. The Axis artillery went stilled, and for a long moment, all seemed almost quiet. Then the Luftwaffe came, small planes buzzing toward the lines, flying low. The Allied anti-aircraft guns boomed, machine guns screamed, and the planes were beaten back.

The first tank screens engaged the line at several different points. The tanks suffered losses everywhere they went, and as the infantry deployed from their transports the full weight of the Allied firepower was unleashed at last. The enemy was now close. As planned, artillery, mortars and machine guns were simply devastating at this range. The suddenness of the assault caused the enemy to fall back. Their losses were heavy.

There were casualties on the Allied side, and more than one gun emplacement was knocked out, but at no point were the attackers able to penetrate the defences. By the time morning had waned into afternoon their infantry had retreated and dug in four miles away from the Allied positions.

The Allies kept up a constant rain of shells. They fired anywhere the enemy armour showed itself, and their anti-aircraft positions kept any attacks from the air at bay. In a last desperate attempt, the surviving infantry, more than a thousand strong, grouped together with the remaining tanks and attempted a frontal assault. They disappeared under a relentless wall of shell, bullet and mortar fire. There was no hope of success.

It was approaching evening when the order was at last given to withdraw back to the Mareth line. The attackers had lost seven hundred men and more than fifty tanks and had achieved almost nothing in return.

The Allies recorded a hundred and thirty men killed or wounded, but their plans for a full-scale attack on the Mareth line remained unchanged and proceeded successfully at the end of the month. Rommel did not command another battle in the North African Theatre. Instead, he returned to Europe to attempt to convince an increasingly unstable Adolf Hitler of the disastrous reality on the ground in North Africa.

In the North African theatre, fighting dragged on for another two months after Medenine, but the Axis army group Africa was doomed to failure. Exhausted, ragged and utterly defeated, they surrendered to the advancing Allies on May 13th, 1943.