Built using an aniseed ball, a condom, and a bowl of porridge, the limpet mine quickly became a vital part of the Allied arsenal in World War Two.

Setting the Challenge

It was the spring of 1939, and the threat of war was hanging over Europe when Stuart Macrae, the editor of Britain’s Armchair Science magazine, received a mysterious phone call.

A man named Millis Jefferis, who Macrae had never met before, wanted to know more about the powerful magnets featured in an issue of the magazine. The gruff-sounding Jefferis wouldn’t tell Macrae why he needed the information, but he was insistent.

Two days later, Macrae met the mysterious Jefferis for lunch. There he learned that Jefferis worked for a secret branch of the War Office and was trying to develop a new weapon.

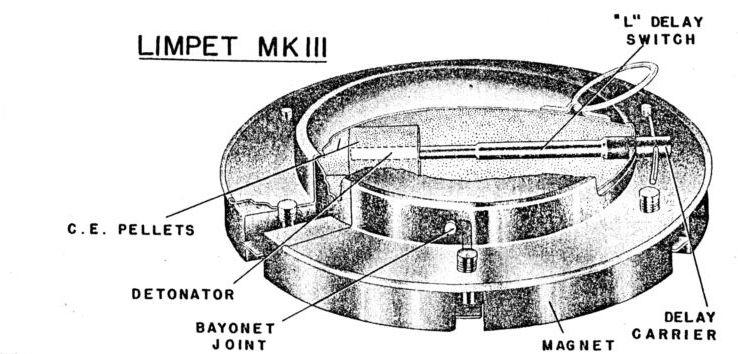

Jefferis wanted to create an explosive with a time delay and a magnetized shell. It would be attached by divers to the hulls of enemy ships, to breach them beneath the waterline and sink them. Jefferis had not been able to find a reliable enough trigger or a powerful enough magnet – hence the call about the magazine article.

Well fed and plied with alcohol at Jefferis’s expense, Macrae offered to take on the challenge. A former engineer, he was confident that he could make the weapon work.

But once he sobered up, he realized that he was going to need help.

The Caravan Maker

Fortunately, Macrae knew just the man for the job.

Cecil Clarke was an inventor and caravan maker from Bedfordshire. He was continually looking for ways to improve his caravans. Two years earlier, Macrae had met him while editing Caravan and Trailer magazine. He had seen Clarke’s workshop and witnessed his passion for creating novel solutions.

Macrae returned to Clarke’s home, where he was greeted with enthusiasm. Clarke was fascinated by the challenge Jefferis had presented. Together, he and Macrae set about trying to solve it.

After discussing their ideas for the mine, they went into Bedford. There, they bought large tin bowls from a Woolworths department store and high-powered magnets from a hardware store. They commissioned a custom-made grooved metal ring from a tinsmith.

Using these parts, they assembled their trial mine. The ring was screwed onto the bowl and bitumen fixed the magnets inside the ring. The device was then filled with porridge in place of the blasting gelatine that would give the final version its explosive power. A watertight lid was fixed on top.

After several tries, they created a device that seemed light enough for the magnets to hold it in place. Now they needed to test it.

Sweets and Swimming Pools

The janitor at Bedford Public Baths might have been surprised when he was approached by two men claiming to be doing secret government work. Nevertheless, he agreed to let Clarke and Macrae use the baths after hours to test their top secret project.

The inventors placed a large steel plate in one end of the pool as a stand-in for the hull of a ship. Then Clarke strapped the porridge mine to himself and swam back and forth, playing at being a saboteur. Eventually, he removed the device from his belt, attached it to the plate, and swam away again.

The magnetic side of the mine was a success. Now came the second challenge: the trigger.

The bomb needed a reliable time detonator. If it exploded too late, it might be found before it could do its job. Too soon, and it could kill the diver.

Clarke created an ingenious trigger device. A striker would be driven into the explosives by a spring. Held back by a pellet, it would only trigger once that pellet had been dissolved by the surrounding water.

The problem was creating a pellet that would dissolve in a consistent amount of time. Some of the ones they made were too loose and dissolved too quickly. Others didn’t dissolve at all.

They found their solution in the candy being eaten by Clarke’s children, namely aniseed balls. Testing revealed that these slowly and reliably dissolved in water in just over half an hour, which was perfect for the device.

Clarke and Macrae bought every aniseed ball in Bedford’s shops to make sure they had enough for their devices.

If that purchase raised questions from shopkeepers, Clarke and Macrae’s next shopping trip raised even more. Needing something to keep each aniseed ball dry until the mine was in place, they bought up the town’s supply of condoms to cover the trigger mechanisms.

Mass Production

Macrae and Clarke gave their invention the name “limpet” and presented it to Jefferis. He was deeply impressed. The two men had created a light, powerful weapon for only £6 per mine, including labor. It was exactly what the military needed. Soon, Jefferis had Clarke producing hundreds of limpet mines at his caravan workshop.

After adding commission for Macrae, the inventors charged the government £8 per mine. Both men made around £500 for the first batch and £2,000 for the next, as Jefferis increased his demands.

Clarke had to start buying aniseed balls direct from the manufacturer. He also commissioned miniature condoms from a rubber company to cover a smaller firing mechanism.

The limpet mine was used throughout the war. Light and versatile, it was perfect for sabotage operations both on land and at sea. Clarke and Macrae ended up in government employ, significant players in Britain’s specialist armaments program that helped saboteurs set Europe ablaze.

From a bowl of porridge, a small candy, and a condom, the limpet mine went on to remarkable things.