“Why, hell, it was just like an old-time turkey shoot down home!”

This comment from a pilot from the USS Lexington refers to the Battle of the Philippine Sea, when the US Navy won a major victory, neutralizing the Japanese naval capacity to the point when Japan was no longer able to launch any large-scale operations. This was one of the final turning points of the war in the Pacific and the largest carrier to carrier battle in history.

The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot happened during the amphibious assault on the Mariana Islands. The archipelago is located in the western part of the North Pacific Ocean, and it held great strategic importance during the war, for it was a suitable spot for Allied airstrips to launch raids on the Japanese mainland.

The Japanese Army had already lost the bulk of its skilled pilots who were able to perform aircraft carrier take-offs, during campaigns such as the Midway and the Solomon Islands. Since the death of Admiral Yamamoto, the man behind the Pearl Harbor attack, Admiral Mineichi Koga took his place. Koga relied on the doctrine established in the Russo-Japanese War, called the Kantai Kessen. The Kantai Kessen or the “decisive battle” was intended to even the odds against the technologically, numerically and industrially superior enemy. By 1944, all hopes of winning the war had nearly vanished.

The initial plan of the Japanese in early 1944 was to attack the US Navy Pacific Fleet, whenever it was on the offensive, thus achieving the conditions for the “decisive battle”. The US offensive was delayed, as the Americans focused mainly on raids and supply line disruptions. The Japanese were losing their patience, while the USA was seizing power in the Pacific with a constant flow of well-trained men and advanced war technology. The Fast Carrier Task Force under the command of Admiral Marc Mitscher was the vanguard of the American Navy, conducting raids and missions intended to weaken the Japanese land-based airstrips on numerous islands in the Pacific. The Task Force 58, as it was called, achieved great success, after it effectively neutralized the primary central Pacific war base of the Imperial Japanese Navy at Truk Lagoon.

The Japanese saw the Task Force as their main threat. As the preparations for the Marianas Islands invasion were well under way, the Imperial Army decided that the Kantai Kessen was going to take place there. Guam, Tinian, and Saipan, all part of the Mariana Islands, were considered to be the main defense lines by the Japanese commanders.

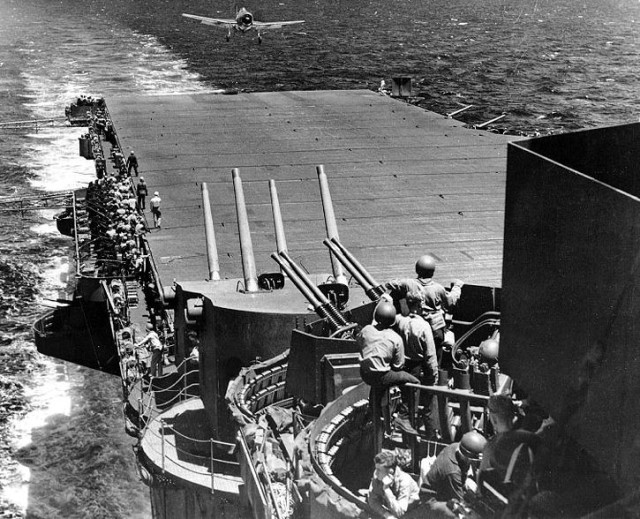

When the amphibious invasion, followed by the Task Force 58 under the guidance of Admiral Mitscher started, the Japanese counter-attack included everything that they could muster. Even though the Americans had a slight advantage in the number of aircraft available, the Japanese had a developed network of airfields on the islands that were intended to support the three aircraft carriers ― Taiho, Shokaku, and Zuikaku. The fleet also included two slower carriers that were converted from ocean liners and two light carriers. They were defended by five battleships, 13 heavy cruisers, six light cruisers, 27 destroyers, six oilers and 24 submarines. The Japanese Navy had 90 warships at its disposal for the “decisive battle”. In addition, they had 450 carrier aircraft and 300 land based planes.

On the other side, the TF-58 was made up of five task groups, 129 warships in total. The carrier groups operated with 956 aircraft. At their disposal were seven battleships supported by 13 light cruisers, 58 destroyers, and 28 submarines.

With the first contact in the early morning of 19th of June, it became apparent that the Japanese pilots were no match for the American fighters and advanced anti-aircraft guns. Within minutes a group of 68 Japanese carrier aircraft was decimated ― 25 planes were shot down, while the US lost only one aircraft. The Task Force launched its Hellcats, which did most of the job, keeping the Japanese 70 miles away from the ships. Out of 42 fighters that were left, 16 were shot down by the US fighters that relieved the initial Hellcats. The Japanese squadron tried to reorganize and charged with 27 remaining planes, causing damage to the USS South Dakota, killing 50 of its crew members. The USS South Dakota remained the only damaged US ship during the battle.

The score continued to rise. The Japanese became impatient and angry. The second wave consisted of 107 aircraft, lost 70 of its planes in the dogfights alone. The rest had some very limited success with taking on two carriers under the command of Rear Admiral Montgomery but were easily repelled. The USS Princeton and USS Enterprise were attacked by torpedo bombers, but their torpedoes failed to hit the targets. Out of 107, 97 aircraft were shot down.

The third wave that was intended to attack the USS Enterprise task group went with fewer casualties for the Japanese, but the attack was highly ineffective.

The fourth Japanese raid was given incorrect coordinates and was forced to abort.

The Great Turkey Shoot went down in history as the day when the Japanese lost 350 planes opposed to the American casualties which were around 30.

On the following day, the US submarines located the Japanese carriers Taiho and Shokaku. A torpedo spread was fired on Taiho, which was in the midst of launching an air raid. The planes that were in air spotted the torpedoes approaching and one of the pilots, Sakio Komatsu, decided to dive in with his aircraft. He collided with the incoming torpedo, which resulted in a premature detonation. Nevertheless, one of the torpedoes managed to hit Taiho, which caused seemingly small damage to the ship. The torpedo ruptured the fuel tanks which lead to a series of explosions. Due to poor damage maintenance, the ship needed to be evacuated.

Another submarine attack was conducted on the Shokaku which resulted in three hits on the starboard side. Ammunition was ignited from the blast, and the ship was heavily damaged and unable to continue operating.

After the US counterattack which sealed the result of the battle, the Japanese casualties were still much higher than American. They lost 645 aircraft through the course of the battle, out of 750 available. The US had 123 planes shot down.

The loss of the two main aircraft carriers was a serious blow to the Japanese Imperial Navy. The decisive battle had ended as a decisive defeat, for it became more than obvious that it was just a matter of time before the US took full control over the Pacific. Nevertheless, the war lasted for one more bloody year, claiming many lives on both sides.