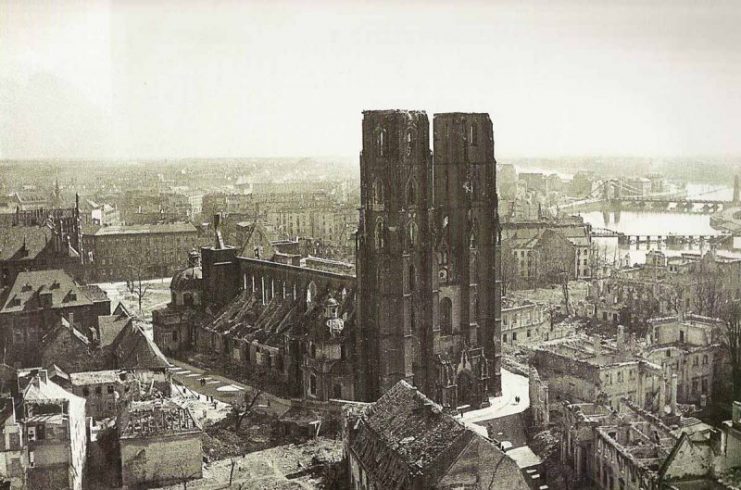

The German town of Breslau – now Wrocław in western Poland – lay untouched by combat for most of the Second World War. But as the Soviet Union pushed west into Germany in early 1945, things changed.

The Fortress City

Breslau was an important focal point for communications in eastern Germany. Recognizing its value, Hitler declared the city to be a fortress in September 1944 and ordered the troops there to hold it to the bitter end.

However, these bold words were not backed up with the resources needed to make them a reality. High command had planned to send three divisions of regular troops to defend each of the fortress cities, but the late war made this impossible.

Strategic bombing had worn away at Germany’s ability to manufacture weapons and ammunition, while years of casualties had chewed up the pool of potential recruits. Fighting the Allies across three fronts – Eastern, Western, and Italian – stretched the available forces thin.

General Hanke, the commandant responsible for defending Breslau, was left reliant on the very old and the very young. Battalions of local volunteers and men past military age made up much of his garrison. A company of engineers, another of signals, and six batteries of artillery were all he initially had by way of professional troops.

To overcome this, Hanke scoured other Silesian units for troops he could use, as well as enforcing rigorous conscription. He pulled together four regiments and an infantry division in this way, and the 269th Infantry Division became the main defensive force for the city. Two trainloads of radio controlled explosive tanks, called Goliaths, were sent to help with the defense.

The Russians Arrive

Since September 1944, Hanke had resisted calls to evacuate Breslau. But as the Russians advanced, he finally relented. From the 19th of January, thousands of refugees started to flee into the depths of winter. But many more were still in the city when the Russians arrived.

The Germans tried to halt the Russians approaching Breslau. SS Fortress Battalion Besselein destroyed a Soviet bridgehead on the Oder on the 8th of February. But another attack out of Liegnitz failed to stop the Russians.

By the 14th of February 1945, Breslau was surrounded by Soviet troops.

The Red Army began attacking the city, testing both the defenders’ morale and the state of the defenses. A direct assault by four divisions broke through the outer defenses and into the city.

Dogged Resistance

As the Russians advanced, they met the sort of desperate resistance also seen in Berlin.

Members of the Hitler Youth took to the streets with Panzerfausts, one-shot anti-tank weapons. With these, they destroyed dozens of Russian vehicles – 76 in a single three-day period.

The SS battalion, together with No. 311 Assault Gun Brigade, managed to drive the Soviets out of the suburbs, through bitter street fighting that saw the combat rage from house to house.

Not every act of resistance paid off. On the 20th of February, Captain Seiffert led the 55th Volkssturm battalion in an attack against the Soviets in a southern park. This formation of the very young and very old was driven back with heavy casualties.

Hanke used the city’s airport to bring in men and supplies, including two battalions of specialist soldiers. To stop this, the Soviets seized the airport, only for the Germans to turn a wide public road into a runway. From here, Red Cross planes took 6,000 of the most heavily wounded men out of the war zone.

Piling on the Pressure

By early March, the Germans were short of men, food, and ammunition. Lacking shells, their artillery could not answer Soviet barrages. Still, they fought on, with doctors working 18-hour shifts to deal with the growing hordes of wounded men.

The Soviets had broken through the outer defenses in several places. Street fighting was now taking place close to the heart of Breslau.

Soviet commanders wanted to free up troops to assault Berlin. From late March, they applied even more pressure in hopes of finishing off the city. Attacks grew fiercer and more frequent. The fighting spread into the sewers as the area held by the Germans shrank.

The situation for people living in German-held Breslau was dire. Many were starving thanks to shortages of food. Suicides rose. Civil unrest, virtually unknown under the brutal authority of the Nazis, began to break out.

Breslau Surrenders

On the 2nd of May, Berlin fell. The Soviet need to free up troops to storm the capital was over, but the pressure on Breslau continued.

On the 4th, a group of churchmen called upon the German leaders in the city to surrender, to save the people from further suffering.

Meanwhile, news arrived that Hanke had been appointed Chief of German Police and Reichsführer SS by Hitler. Though the Führer himself was dead and his empire in ruins, Hanke flew out of Breslau to take up his new roles. He left the city in the hands of General Niehoff.

Niehoff took responsibility for doing what Hanke would not – arranging a surrender. On the 5th of May, he briefed his officers on the situation. On the 6th, at two in the afternoon, he surrendered Breslau to the commander of the 6th Red Army.

On the 7th of May, as the rest of the German army was offering its surrender, the Soviets marched into Breslau. Many of them had seen the horrifying treatment the Nazis had inflicted on their homeland. They returned that brutality upon the poor civilians of Breslau.

Counting the Cost

Breslau had resisted the Soviets for over 70 days. 29,000 German soldiers and civilians were wounded or killed. In return, they inflicted 60,000 casualties on the Soviets.

Hanke disappeared, allegedly killed by the Czechs while trying to escape a POW march, dressed as an SS private. Niehoff spent ten years in a Soviet prison camp. The people of Breslau suffered through the Soviet sacking, before having their city handed over to Poland in the aftermath of the war.

The price for Breslau’s resistance had been high.