Brest Fortress and the town of Brest are located in modern day Belarus. In 1939 the town was conquered by the Germans during the invasion of Poland. The Fortress was handed over to the Soviets as part of the secret agreement on the division of Poland made between the USSR and Nazi Germany.

Little did the Soviet occupiers know that their then-allies would turn into bitter foes just two years later. When the Germans invaded the USSR on June 22, 1941, the Fortress became one of the biggest battles in the early days of Operation Barbarossa.

The siege of the Fortress was part of the initial wave of attacks on the Soviet Union, so it came without prior warning. Hitler, in his familiar fashion, commenced the invasion without a formal declaration of war.

The Red Army garrison was unprepared. A fierce battle led to a siege that lasted for seven days. The garrison was comprised of 9,000 men who represented a combined force of regular soldiers, border guards and NKVD operatives. Apart from the military personnel, the Fortress was inhabited by approximately 300 families belonging to the servicemen.

They were faced by a 20,000 strong Wehrmacht force under the command of the famous tank tactician, General Heinz Guderian. Elements of the 2nd Panzer Army, also known as Panzer Group Guderian, were at the time the vanguard of the German armored forces. Comprised of advanced tanks manned by skilled crews, they had conquered both Poland and France in the earlier years of the war.

The 2nd Panzer Army was at the time equipped with a variety of light and medium tanks which stormed the eastern flatlands in their rapid advance.

Nevertheless, they were held at Brest, to their great surprise, as the siege was predicted to last not more than 12 hours.

The Fortress was shelled without any warning, and the casualties were high. The artillery fire managed to destroy a lot of supplies and equipment. The bombardment was followed by an infantry attack, sent in to finish the job. Even though the Soviets were unable to stage a proper line of defense, they managed to create pockets of resistance which forced the Germans into a game of attrition.

Isolated strong points were defended fiercely, which left the attackers in awe. They had expected to overrun the defending Soviet troops in a matter of hours. The level of determination by the Soviet defenders was at its peak. They were aware that a full-scale attack had been launched all along the border, and their role would be pivotal in delaying the enemy advance towards Moscow.

Having sampled Soviet stubbornness the hard way, the German command decided to go around the Fortress. That way they could continue with the objective of gaining control over the Panzerrollbahn I ― the railway that led to Moscow.

Also, bridges over the River Bug had all been taken on the first day of the invasion, so the Fortress lost its strategic importance. The contingent of troops left to seize control of the Fortress had, therefore, time to force its defenders out.

The Brest Fortress became completely isolated, encircled by Germans who called on its defenders to step down and surrender. They, however, were not giving up. The women tended the wounded, while children scavenged equipment, delivered messages, and scouted enemy movements.

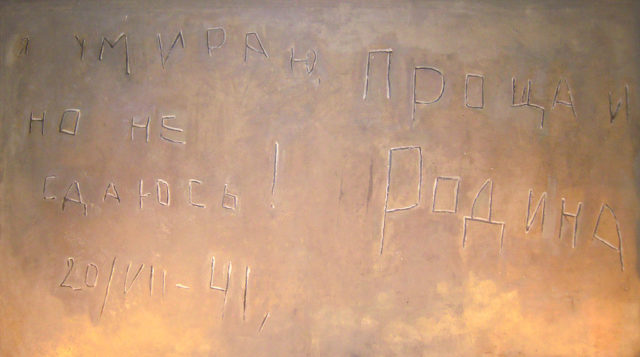

Even though the situation was apparently desperate, the garrison was determined to hold their ground and show the enemy that surrender was not an option.

The fighting was concentrated mostly around the Fortress and its citadel. On June 24, the Soviets, under the command of Captain Ivan Zubachyov, managed to organize a coordinated attempt to break the siege. Zubachyov’s second in command was Regimental Commissar Yefim Fomin. Together they launched a night attack on German positions. It was an infantry charge supported by several Maxim light machine guns.

Even though the attack was well coordinated, the Germans were prepared. Having cut off the defenders’ water supplies, they knew such an attack was imminent. They employed machine-gun nests and concentrated their mortars to suppress this last attempt to break the encirclement. Casualties were high for the Soviet troops. The failure of this counter-attack severely crippled them from staging another offensive, as around 4,000 men had fallen into captivity.

The Germans wanted to minimize their casualties so employed a variety of heavy artillery guns. Also, they brought in rocket mortars ― the 15 cm Nebelwerfer 41 – and resorted to flamethrowers to clear out the buildings occupied by defenders.

On the Soviet side, equipment was scarce apart from their standard-issue Mosin-Nagant rifles. They had to rely on what they captured. They tried to seize as many MG-34 machine guns and MP-40 submachine guns as they could find, to complete their arsenal.

On June 26, most of the citadel had fallen. All remaining defenses were concentrated in the East Fort. The commander of the German 45th Infantry Division, Generalmajor Fritz Schlieper, wrote to the High Command in his detailed report:

“It was impossible to advance here with only infantry at our disposal because the highly-organised rifle and machine-gun fire from the deep gun emplacements and horse-shoe-shaped yard cut down anyone who approached. There was only one solution – to force the Soviets to capitulate through hunger and thirst. We were ready to use any means available to exhaust them… Our offers to give themselves up were unsuccessful…”

The Germans decided to call in the Luftwaffe. After the bombardment, the last 360 defenders surrendered. The siege ended on June 29, 1941. Some historians claim there was continued resistance throughout the next two months by guerrilla soldiers who were well hidden. They harassed the enemy continuously. One such incident was registered to have happened on July 23, when a shootout occurred, after which a Soviet officer was captured.