The infantry was one of the largest elements of the United States Army during the Second World War. Sadly, it was also one of the weakest. Though many infantrymen fought with skill and courage, the infantry as an institution didn’t meet their commanders’ expectations.

What caused this problem? And what did high command do to try to fix it?

The Recruitment System

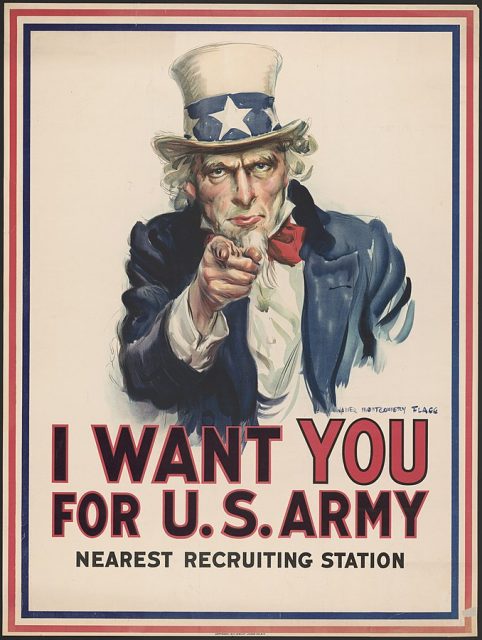

Every army has to decide how to prioritize its human resources. During the Second World War, the fighting nations all followed a similar pattern, turning their best recruits into specialists. In particular, many of the best-educated and fittest men were siphoned off into the technical branches and air forces.

The United States took this to extremes. Recruits could choose their specialty and very few chose the not so glamorous, yet still extremely dangerous work of the ordinary fighting infantryman. Those who wanted to carry a rifle and face the enemy up close were better off applying to be marines or paratroopers, which were far more prestigious roles. Only 5% of the men who volunteered in 1942 chose the infantry or armor.

The result was a severe shortage of quality infantry recruits. Prioritizing specialist services was good for other parts of the armed forces, but even the official histories of the US Armed Forces acknowledged that this led to a dangerously low proportion of effective infantry.

https://youtu.be/TjUU6961HEQ

Crippling Casualties

The situation was exacerbated by high casualties. Statistics compiled in March 1944, before the army had even engaged in the great campaign to reconquer Western Europe, showed that the infantry had suffered 53% of army casualties, despite making up only 6% of its personnel. The figure rose even higher during the Normandy campaign.

These losses meant that the infantry constantly had to bring in replacement troops. An alarming proportion of the men lacked combat experience, and units lacked the experience of working together.

It was a vicious circle. High casualties limited the buildup of experience and competence within units, leading to higher casualties.

Unit Building

Though the Americans were happy to prioritize specialist services, they took a more egalitarian approach within the infantry. Every effort was made to bring all infantry formations to the same level of quality so that all could serve equally well wherever they were needed.

This was the opposite of the German approach, and when the two armies faced each other in Normandy, it proved to be a mistake. The Germans had built up elite and low-grade units, to be used in different circumstances. The elite units let them achieve significant victories, while the low-grade ones did their job of filling lines and soaking up casualties. Egalitarianism put the American infantry at a disadvantage.

Results

Just as the problem of the infantry had several causes, it also had several symptoms. Most of these men were the leftovers, the ones no other service had wanted, and that showed.

These troops were of relatively poor quality compared with the rest. The average infantryman was an inch shorter than men in the rest of the army. Height was a reliable indicator of general physique, meaning that they were not as strong and tough as others.

Standards of leadership were poor. Again and again, the critical men called upon to lead others into battle did not live up to their roles.

A failure of training meant that coordination was weak. In particular, the infantry was not trained or equipped to work with tanks. Joint operations involving these two forces were central to the fighting in Europe, where tanks and infantry covered for each other’s weaknesses and benefited from each other’s strengths. Both the Americans and the British struggled to make this work.

Fighting Spirit

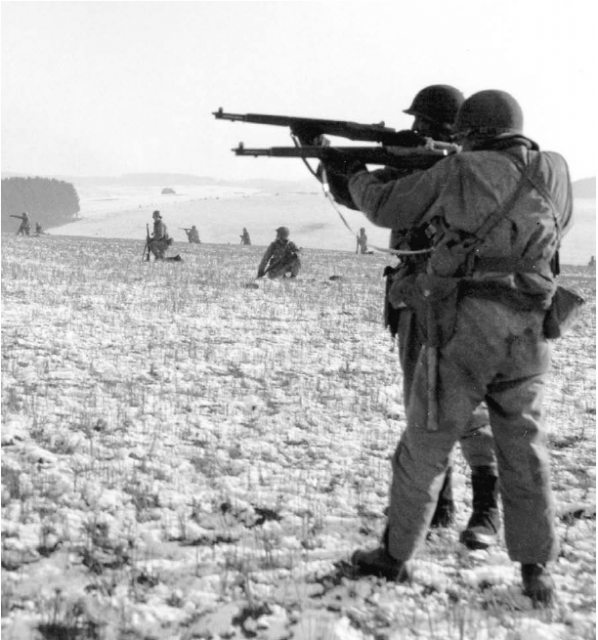

The worst symptom was a poor fighting spirit. Many infantrymen lacked the boldness and self-belief needed to make them into effective soldiers. They relied on the artillery to take out enemies and so allow them to advance unhindered. When faced with serious opposition, they faltered, unable to believe that they could overcome a foe.

Despite being trained to fire as they advanced, and so to suppress enemy activity, these men were reluctant to shoot if they couldn’t see a target. When targets were visible, many American infantrymen were busy taking cover or pressing themselves against the ground, trying to avoid being shot at.

A report from General Clark, reflecting on operations in Italy, said that infantry suffered heavy casualties and that to be effective they had to have the courage to advance despite the danger and losses. On far too many occasions, the American infantry lacked the aggressive spirit to do this.

Fixing the Problem

By the spring of 1944, the problem had been identified. Official reports within the army shocked commanders into action.

To counter the recruitment problem, a hunt began for both officers and men who could be diverted from other forces. Among those deprived of their promised choice of service were 30,000 aviation cadets transferred into the army in March 1944, mostly into the infantry.

It was the beginning of a solution, but it brought its own problems. Of the men transferred to infantry units in Normandy that summer, only 37% had training in using a rifle. Recruitment needed to be paired with effective training and unit building.

General Bradley and his commanders effectively undid the lack of a fighting elite, as they came to rely on such effective units as the 1st and 4th divisions. These units had the experience of fighting in war forged divisions and thus had a stronger spirit, on which commanders could rely for the tough tasks.

The infantry remained a relatively weak feature the US Army throughout World War Two. This is reflected in how little attention it has since been given compared with other forces. But despite their failings, the infantry endured through heavy casualties and grew stronger as a fighting force, helping the Allies to emerge triumphant from the war.

The failings of the infantry lay not in the character of the individual soldiers, but in the way the force was forged.