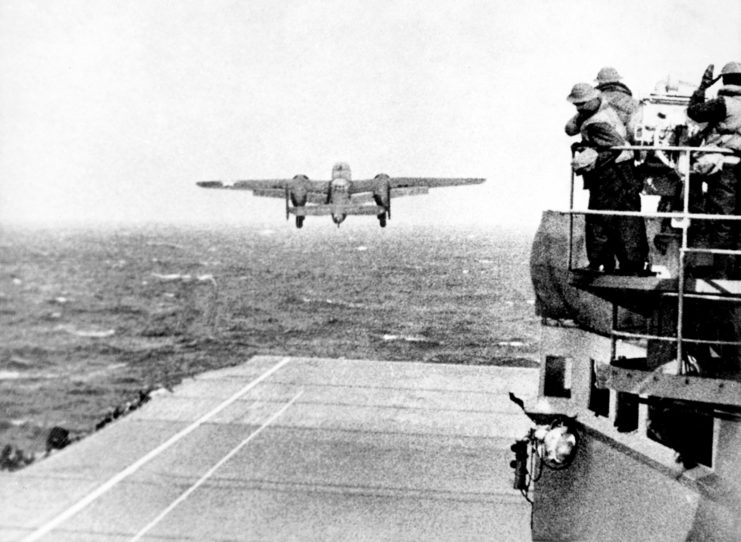

On April 18, 1942, the United States responded to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor by doing something that had never been done before: launching bombers from an aircraft carrier. There were hurdles to overcome, and the plan was forced to adapt, but once the mission was set in motion, the US Navy and Air Force were able to collaborate and successfully bomb Japan.

Franklin Roosevelt’s response to Pearl Harbor

Casualties were calculated following Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, and the whooping 2,400 dead made US President Franklin Roosevelt want to retaliate. His hopes were not only for revenge, but that a counterattack may raise morale in America during what felt like some of the darkest days of the war.

At the time, it didn’t seem fathomable to do an air raid over Japan – that is, until Navy Capt. Francis S. Low, an expert in submarine warfare on Adm. Ernest J. King’s staff, came up with an innovative idea.

Low asked King if it would be possible to launch bombers off of the deck of an aircraft carrier. The idea was passed around quietly to see if it were possible, and Lt. Col. James Doolittle was approached with the ambiguous question of which bomber was most feasible.

Unaware of the purpose of the question, Doolittle determined that, with modifications, the North American B-25 Mitchell was the most suitable option to successfully take off from an aircraft carrier, despite having not yet seen combat. It was only after he came to this conclusion that he was filled in on the mission’s intentions.

A top-secret mission

The mission was to include 16 B-25s brought within 450 miles of Tokyo by the USS Hornet (CV-8). From there, the crews would takeoff in the bombers and maintain treetop level until they were over their target. Once overtop, they would rise in altitude, drop their bombs and return to treetop level, after which they would fly off the rest of their fuel before landing in unoccupied China.

The mission was so top secret that the call for pilots from the 17th Bombardment Group described nothing about the mission, except that it was highly dangerous. This didn’t stop a plethora of volunteers from pouring in. Even in training, the men were not made abreast of what they were training for.

Of course, given the nature of training, which included cross-country flying, low-altitude bombing, low-level and night flying, navigation and learning to takeoff from a runway as short as a flight deck on an aircraft carrier, the men could make their own conclusions.

Modified B-25 Mitchell bombers included broomsticks for tail guns

The B-25s were deemed best for the job, but with the stipulation that they be heavily modified for the specific task at hand. The bombers needed to significantly decrease in weight if the mission was to be pulled off, so everything deemed “non-essential” was stripped. The heavy radios were removed, as were the lower gun turrets. The Norden bombsight, which was notably bulky and heavy, was replaced with a much lighter version made from 20-cent aluminum.

Additionally, the B-25s were not readily equipped for long-range flying and needed to be modified. Each was given extra fuel tanks that nearly doubled the 646 gallons originally equipped on the aircraft to 1,140 gallons.

Notably, the tail guns on the aircraft were removed, but in an effort to try and fool Japanese pilots into thinking they were still equipped, they were replaced with broomstick handles that were painted black. They actually looked like tail guns, as long as the enemy didn’t fly too close.

The Doolittle Raid didn’t go exactly as planned

Originally, the plan was to take off at dusk, approximately 400-600 miles from Tokyo. The pilots would then bomb the Japanese targets at night and proceed toward unoccupied China in the morning.

When two Japanese picket boats were detected by the Navy, the mission had to be sped up. They’d spotted the aircraft carrier, and the Navy had heard the radio transmission they’d made to warn of the presence of the Americans. This forced Vice Adm. William Halsey Jr. to make the call to launch the bombers earlier than planned.

Of the 16 bombers that were launched, 14 hit their targets – including in Tokyo, Yokosuka, Kobe, Yokohama and Nagoya – and made their way to the Chinese coast. One came under attack by Japanese fighter aircraft and dropped its munitions into Tokyo Bay. The alternative plan, if the crews were unable to make it, was to fly as far west as possible, ditch their aircraft at sea and use the rubber boats provided to make their way to shore.

Most of the crews were successful in making it to China, but one was forced to land in the Soviet Union, where they were interned at various locations, until their escape a year later. Two others were captured by the Japanese. There were only a few fatalities during the mission, caused by accidents during bail-outs, crash landings or execution by the Japanese.

A turning point for the Allies in the war

It’s estimated that nearly 14 tons of explosive and incendiary bombs were dropped on the Japanese mainland on April 18, 1942. While they did comparatively little damage than other raids, the psychological effect was immense.

While the Japanese had not entirely ruled out the possibility of an American air raid on the home islands following the attack on Pearl Harbor, they weren’t expecting it, so the US had the element of surprise. When the reality set in that American bombers could fly over Japan, the country’s military was forced to accelerate the expansion of its defensive perimeter, thinning defences over a wider area.

More from us: Why the Battle of Ortona Was Nicknamed the ‘Italian Stalingrad’

The success of the Doolittle Raid did exactly what Roosevelt had intended: lift morale in America. The Japanese were forced to slow their forces in the Pacific Theater, and the mission became one of many turning points for the US and Allied forces.