The United States Coast Guard was founded on a tradition of taking small boats into dangerous conditions to save lives. This skill made Coast Guard coxswains an indispensable part of the Pacific Theater during World War 2. Combining with the US Navy during wartime, Coast Guardsmen proved their worth time and time again as they expertly handled small landing craft in and out of almost any situation. No man better exemplifies this prowess than Douglas A. Munro.

Born in Vancouver in 1919, Douglas Munro attended Cle Elum High School in Washington state and graduated in 1937. He attended the Central Washington College of Education for a year before enlisting in the Coast Guard in 1939. He spent his first two years on board the Cutter Spencer, a 327-foot Treasury-class cutter which patrolled out of New York, and later Boston.

While on the Spencer, Munro advanced quickly, making Signalman 2nd Class by the end of 1941. After the Spencer, he transferred to the Hunter Ligget, a Coast Guard-crewed landing craft patrolling in the Pacific. In 1942 he was made a part of Transport Division Seventeen, helping to coordinate, direct, and train other troops for amphibious assaults.

The United States’ first taste of this warfare was at Guadalcanal, a strategically located island in the Solomon Islands chain. After the initial Marine landings, a base was established at Lunga Point. Munro was assigned here along with other Coast Guard and Navy personnel to operate the small boats and assist with communications.

This small base, which served as a staging point for further troop movements, consisted of little more than a house, a signal tower and a number of small craft and supplies deposited from the larger troopships.

After the Marines had moved west of Lunga point, they encountered an entrenched Japanese position on the far side of the Manatikau river. It was clear that an attack across the river would be fruitless, and a plan was devised to bring men down the coast, to land west of the Japanese position, allowing it to be attacked from both sides. To achieve this goal Marine Lieutenant Colonel Lewis “Chesty” Puller placed men from the 7th Marine Division onto landing craft and began an assault on September 27th.

These landing craft were led by Douglas Munro, who took the men into a small bay just west of Point Cruz and delivered the entire 500 man force unopposed. Meanwhile, the destroyer USS Monssen laid down supporting fire and protected the Marines’ advance. The men advanced quickly up to a hill south of the landing zone and dug in.

Meanwhile, Munro and his crews returned to Lunga point to refit and refuel, leaving a single LCP(L) (a 36-foot landing craft, lightly armed and made mostly of plywood) to provide evacuation for any immediate casualties.

But less than an hour after the initial landing the operation began to deteriorate. First, a flight of Japanese bombers attacked the Monssen, forcing her to retreat and leaving the Marines without heavy fire support. Then the Japanese launched an infantry attack on the Marines. The Japanese had stayed to the north of the Marine landing force, near a rocky cliff known as Point Cruz. Their attack to the southwest was designed to cut the Marines off from their escape route, while also closing in on the bay where the Marines had landed.

There the single LCP(L) still sat, manned by Navy Coxswain Samuel Roberts and Coast Gaurd Petty Officer Ray Evans. The men had gotten close into shore for a speedy evacuation, but this left them vulnerable. A sudden burst of Japanese machine gun fire alerted them to the enemy’s presence and damaged their controls in the process. Roberts managed to jury rig the rudder but was fatally wounded in the process, Evans jammed the throttle forward, speeding back to Lunga Point to tell the men what was happening.

The trapped Marines hadn’t brought their cumbersome and heavy radios with them, and couldn’t signal back to their support. In desperation, they spelled out “HELP” by laying out their undershirts on a hillside. Luckily this was noticed by a Navy dive bomber pilot who reported it back to the sailors at Lunga. Because of this, by the time Evans’ LCP(L) made it back Munro and his men were already aware that something wasn’t going right.

Thanks to Evans they now had the detailed information needed to make a plan of action. It was determined that a group of small boats and troop transports would have to return, under fire, to get the men out of the combat zone. Munro immediately volunteered to lead the operation and got ten boats readied and underway as soon as possible.

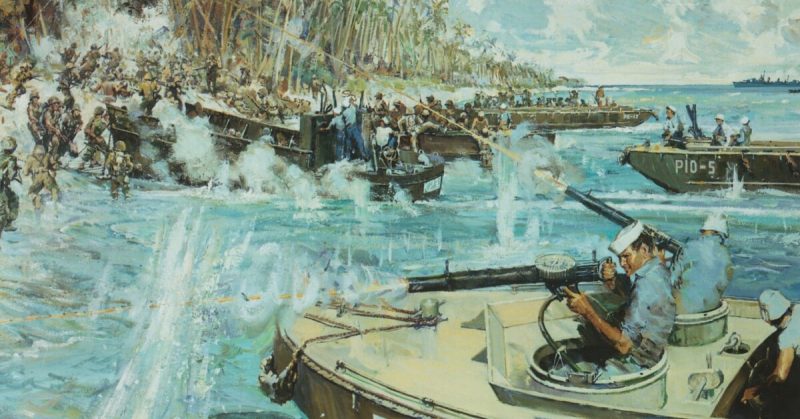

This small flotilla came into the bay under fire, a stark difference to the peacefulness of the first landing. Thanks to fire support from USS Monssen, which had returned to combat after the bombing raid earlier, a path was cleared for the entrapped Marines to rush to the beach. Munro directed his landing craft to begin ferrying the men back to the Monssen, while he and the other LCP(L)s provided fire support.

By this time the Japanese had taken up positions on all three sides of the bay, and were able to coordinate a devastating barrage of fire on the retreating men. Seeing this, Munro positioned his own craft between the enemy and the landing crafts to provide support by fire.

The evacuation was going smoothly, but after the last men were coming off the beach, a landing craft became grounded, and couldn’t pull away. Munro ordered another craft to tow it free while he provided support, again putting his own boat in harm’s way to help save as many men as possible. While Munro’s boat was taking position to do this, a Japanese machine gun crew was setting up on the beach.

Petty Officer Evans, who was Munro’s coxswain, saw this and called out for him to get down, but either from the sound of the engine or his own machine gun fire Munro couldn’t hear him. The Japanese machine gunners were able to hit Munro, fatally wounding him. Evans pulled away, and along with the rest of landing craft, headed back to Lunga Point; with all of the Marines saved their job now was to survive and get back in one piece.

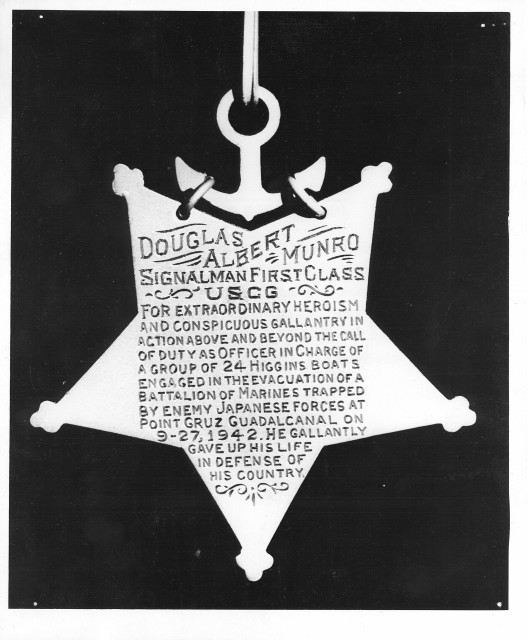

Thanks to Munro’s heroism, his swiftness of action, and excellent leadership, 500 Marines made it off the beach that day, and for this, Signalman 1st Class Douglas A. Munro was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal Of Honor, the highest military award available to United States Servicemen. The 500 men he saved went on to help capture the Matanikau River early in October, which meant the beginning of the end for Japanese forces on Guadalcanal, who never fully recovered from that defeat.

Munro’s body is interred in his hometown of Cle Elum, Washington, and his Medal of Honor is on display at United States Coast Guard Training Center Cape May, New Jersey, where it serves an everlasting example to new recruits about what it means to truly be a United States Coast Guardsmen.