The Battle of the Bulge, which took place between December 1944 and January ’45, was a turning point in the Allies’ fight against the Germans toward the end of the Second World War. Launched by the Germans, who’d hoped a surprise attack would turn the the conflict back in their favor, it wound up being a devastating campaign that led to insurmountable casualties and the Führer‘s forces running out of steam in Western Europe.

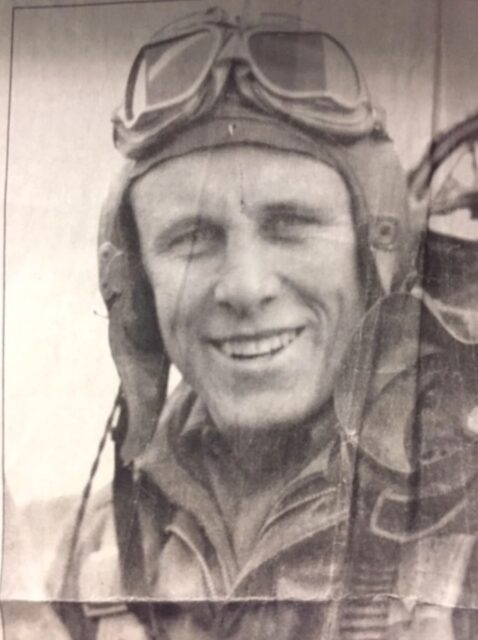

While much of the fighting took place on the ground, aerial engagements occurred in the skies over Belgium, with one of the men involved being American Lt. Edwin “Ed” Cottrell, who found himself escorted back to friendly lines by unexpected allies.

Ed Cottrell and the Battle of the Bulge

Ed Cottrell was a young airman serving with the US Army Air Forces’ (USAAF) 493rd Fighter Squadron, 48th Fighter Group at the time the Ardennes Offensive kicked off. He and his comrades were given one task that was to be repeated over the course of the battle: support the Allied ground forces by targeting German tanks and equipment from the sky.

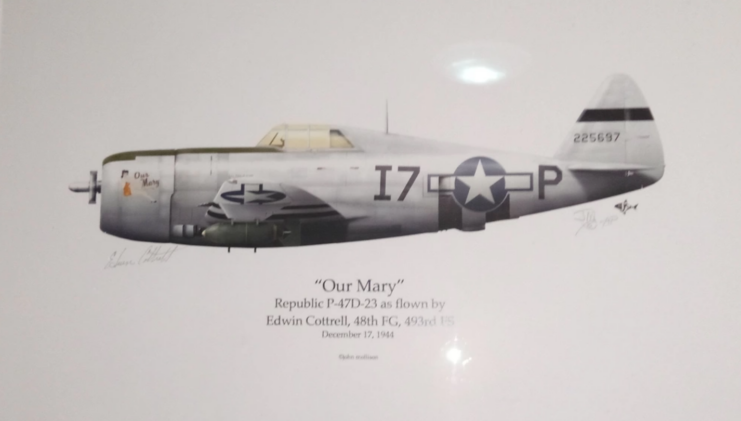

To do this, Cottrell piloted a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, which he’d nicknamed “Our Mary.”

On December 17, 1944, Cottrell and the 493rd took off from their snow-covered base. Each P-47 was carrying a payload of bombs, which would be dropped during a low-altitude strike against a convoy of Tiger tanks. As they flew over fields, forests and war-torn towns, they kept the importance of their mission at the forefront of their minds.

Things were going smoothly… at first

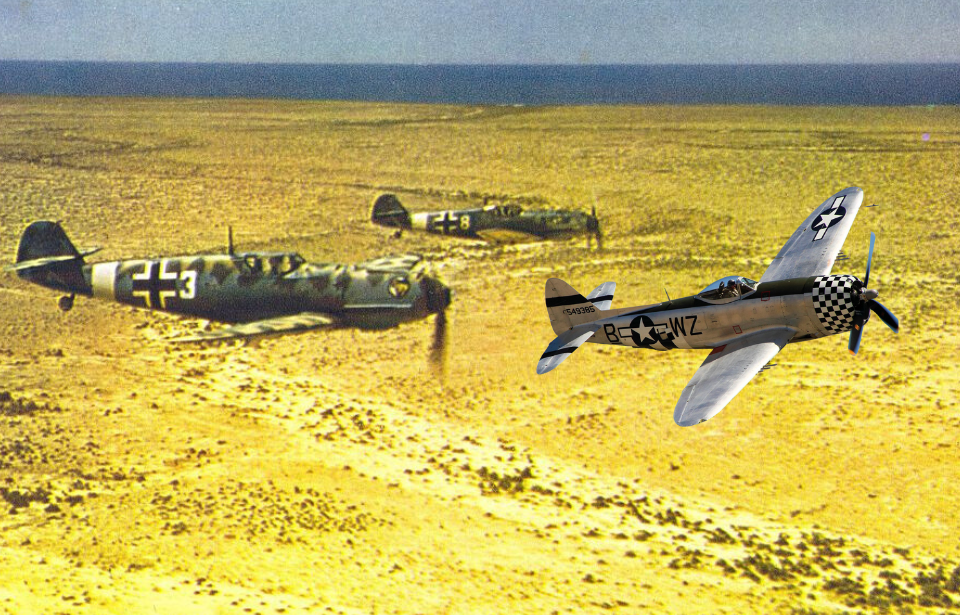

The first portion of the mission went off without a hitch, with Ed Cottrell and the other P-47 Thunderbolt pilots flying toward the convoy of German tanks and vehicles. However, things quickly took a turn when Luftwaffe-flown Messerschmitt Bf 109s made an appearance on the horizon; the Americans had been ambushed.

Amid the chaos and gunfire, Cottrell kept his cool. His squadron leader had already dropped his payload and left the scene, and the lieutenant made an attempt to follow him. However, his aircraft took a direct hit from an enemy 20 mm cannon, taking out eight cylinders of his Pratt & Whitney engine. The damage caused oil to spray across the P-47’s cockpit, obscuring the aviator’s vision. Before he knew it, Cottrell was losing altitude – and fast.

“I opened the canopy, got on the radio to my commander and said I’d been hit and was heading west and going to fly the plane as far as I could,” he told the Veterans History Museum of the Carolinas. “The plane sort of kicked out but it chugged along at about 120 miles an hour with oil flying out all over my windshield.”

Catching Ed Cottrell off-guard

Aware he was, essentially, a sitting duck, Ed Cottrell braced himself for the worst. However, something unexpected happened. Instead of delivering what would have undoubtedly been the final blow, two German pilots pulled up alongside Cottrell’s P-47 Thunderbolt and escorted him out of the combat zone.

Once out of imminent danger, the two Bf 109s peeled off, leaving Cottrell to make a solo emergency landing at a nearby air field. While his aircraft was damaged, he was, to his relief, unharmed – and, most importantly, alive. Astounded at his luck, he exited the P-47 and immediately kissed the ground.

It was a remarkable act of mercy that left the American airman bewildered and relieved. Understandably, the experience changed his view of the war and those involved. It served as a reminder that, despite the horrors both sides were experiencing, compassion could still appear.

What happened to Ed Cottrell after World War II?

Ed Cottrell continued to serve for the remainder of the Battle of the Bulge, and over the course of World War II flew 65 missions. In the decades following the conflict, he remained with the military, enlisting in the US Air Force Reserve. “I joined the Air Force Reserves to make a little extra money and still serve the country,” he told the Veterans History Museum of the Carolinas.

“When the Air Force Academy was being developed in Colorado Springs, I was assigned to go around to high schools and explain to kids and guidance counselors what the academy was about, what it was like to go to the academy, and get them interested in becoming cadets,” he continued. “I told them how difficult it was and the discipline that was required, so that if they came to the academy, they didn’t wash out. I stayed in the reserves for 28 years and retired.”

Upon his retirement, Cottrell had reached the rank of colonel.

While initially hesitant to talk about his wartime experiences, Cottrell eventually changed his tune and began relaying his story to those willing to listen. “For a long time, I didn’t talk about the war,” he said. “I wanted to forget it. Then about 15 years ago, at one of our squadron reunions, we talked about how the country was different now.”

More from us: Aaron Bank: The ‘Father of the Green Berets’ Who Revolutionized Special Warfare

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!