The following is an excerpt from a 40,000-word manuscript written by Philippe Defechereux about Manny’s life, from growing up in an autocratic environment, to the democracy he enjoyed after becoming an American citizen following the war. This particular part examines his service aboard Lützow and his transfer to Berlin toward the end of the conflict.

Emmanuel von König’s parents met in the aftermath of World War I

Emanuel von König’s parents were introduced to one another in Munich in late 1921. Both had been involved in World War I, though each in a quite different manner. When they met, Ludwig, then 27, was a land surveyor with the Bavarian state. Élise Jadoul, born in Liège, Belgium, in 1892, had found herself in southern Germany shortly before the conflict ended in November 1918.

From the summer of that year to the day she met Ludwig, Élise went through a life experience almost beyond belief, although it hardly affected her great beauty and excellent upbringing.

The pair got along well in Munich – both were Catholic, matching the majority of Bavarians – and [they] married in October 1922. They lived on the top level of a multi-unit five-floor street building. Theirs was relatively comfortable multi-room apartment with a view of the Isar. [While] the neighborhood was modest, it was conveniently not far from the city center.

Growing the family

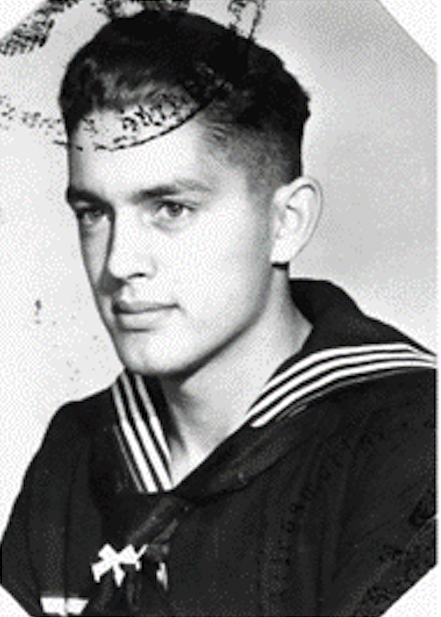

Ludwig and Èlise von König’s first child, a girl, was born on November 8, 1925. She was named Wolfhilde, [for] her grandmother. A little brother was born on March 16, 1927 and named Emanuel.

Munich was known for its excellent schools and both children benefit from that. In January 1933, however, a new chancellor, soon to be known as “der Führer,” was elected. Within a year, he and his party, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, began to bring major changes to the interior and exterior policies of Germany.

The von König family appears to have adapted to this seamlessly, although Emanuel, called “Manny” by all, would be enrolled in the Military Youth program, ordered by the regime after age 10. He soon learned paramilitary skills and, at 16, gradually became involved in direct combat as an anti-aircraft gunner.

As he’d always dream to be part of the Kriegsmarine, he twice attended the prestigious Flensburg-Mürwik Naval Academy, including in late 1944. That’s how we found him aboard the pocket battleship KMS Lützow in mid-April 1945.

Emanuel von König needed to undergo a minor surgery

Shortly after dawn on April 16, 1945, young sailor Emanuel von König awoke in his Kriegsmarine warship bunk, apprehensive about the day ahead.

This feeling was not born out of any fear of the war dangers that might spring upon his mighty vessel at a moment’s notice. To the contrary, the dedicated anti-aircraft gunner felt thwarted for having to take a short leave from his duty for a surgical appointment at 10:00 AM. A slight combat wound he had incurred the day before required him to have minor surgery in a hospital.

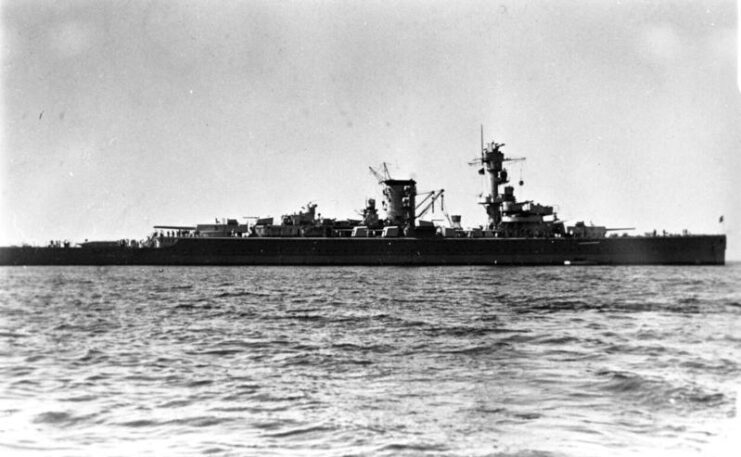

The nearest one stood five miles to the north in the main German port of Swinemünde (today Poland’s Świnoujście) on the Baltic coast of Pomerania. That was, in fact, the current port of call of the KMS Lützow, the heavy cruiser von König had served aboard since January 5, in his first and long-desired Kriegsmarine assignment.

Assigned to the KMS Lützow

Emanuel von Köning had arrived aboard when Lützow was in action along the Soviet-besieged coast of East Prussia, not far from its capital of Königsberg (today Russia’s Kaliningrad). Although he would be back on the ship by evening, the potent cruiser upon which he had, by now, served through long hellish moments since his first day of duty was being readied that morning for another intense day of action.

Moored deep into the greater Oder estuary since April 10, Lützow’s six powerful, long-range 11-inch guns, whose high-explosive shells could destroy targets as far as 22 miles away, were in wait for wreaking more havoc upon the Soviet tank columns already advancing on the mainland further south and that were soon expected to rush westward en masse toward Berlin.

“Manny,” as everyone had called him since his toddler years in Munich, served a crew member for one of the 14 anti-aircraft gun turrets protecting his ship. [While] the Soviet Air Force was, by now, in full control of the skies, its impact on large well-defended structures was limited by a lack of four-engined, high-altitude bombers, the only aircraft type that could carry the large ordnance capable of severely damaging Lützow’s thick armor.

Still, the small but aggressive swarms of strafing MiGs and Yakovlevs that often flew overhead had to be kept away from inflicting any damage on the cruiser’s crew, or [the] soldiers guarding nearby support infrastructure.

While he was in the hospital, would Manny miss such action, a task he so cherished and was so good at? He already knew of a different precious occasion he would miss: a special dinner planned by Kapitän Bodo-Heinrich Knoke that very day for 5:00 PM. [In] his mind, this made his medical appointment even more ill-timed. Manny, who had just turned 18 a month earlier, much enjoyed good food and crew camaraderie.

Enjoying a hearty breakfast aboard the KMS Lützow

By 8:00 AM, proudly wearing his stylish dark blue uniform, sporting a white stripe-trimmed collar, the handsome, dark-haired sailor wolfed down a hearty breakfast- and such they were on Lützow, as he had described from his ship in a letter to his mother and sister, still in Munich, on February 10:

“The provisions are great. The cook is good enough to compete with you. For breakfast, 40 grams of butter and 40 grams of pork fat … Forty grams of butter! Like God in France. We eat well because the work, especially while out at sea, is hard.”

Großadmiral Karl Dönitz, head of the Kriegsmarine, obviously took the best of care for his men.

Emanuel von König was indoctrinated from a young age

One hour later, as Emanuel von König looked up from the ship’s deck while waiting for a vehicle to take him to the hospital, he stared in wonder at a pure blue sky made brilliant by a bright sun, while a soft wind ruffled the large [symbol]-struck flag on the warship’s stern mast. Perhaps this vision triggered in his mind the lyrics and tune of the “Banner Song” (Fahnen Lied in German) he had sung hundreds of time during his countless but craftily organized Youth meetings:

“Our banner leads us forward / Our banner is the new times / Our banner guides us into eternity / Yes, our banner means more to us than death.”

That banner, of course, was the red and white [National Socialist German Workers’ Party] flag. Cunningly, those basic colors were borrowed from the German Empire’s flag of 1914-19. [The Führer] had himself adapted the [symbol] from related [ones] that had come to his his attention in 1920.

Right at this moment, [in] mid-April 1945, that banner seemed to the outside world to be leading the entire [regime] into its final extinction, but not yet for most Germans, especially the fighting men, for whom a steady flow of propaganda lies over the years had [turned] a hallucination of objective facts into a maddeningly twisted reality broadcast to them daily from on-high. A perfect example is this war diary entry from Manny’s sister, dated April 1:

“Easter. The festival of joy and of spring. Festival of the children. … Today is also April 1st. Yet no one is in the mood for pranks. The Russians have penetrated the Viennese Neustadt. One sees no holding of the line and turning the tide. But the heart tells us, ‘Stick it out.’ … I put my faith in the Führer. He will continue to guide us; he knows what he’s doing.”

It was the same for Manny, who, while aware that a massive Soviet onslaught toward Berlin was, at some point, going to rage further south, still kept faith in eventual victory, as did most of his shipmates. In fact, he thought the warship aboard which he crewed was in [her] new position to help achieve just that.

In a February 5 letter to his family, he had written, “The terror is just beginning: the great offensives from the East and West. But we will hold out. … We wait for them and will show our sharp teeth. … We all have our hopes for victory.”

Let the reader keep in mind his tender age and degree of indoctrination before forming a judgment.

Assessing the damage caused by RAF bombers

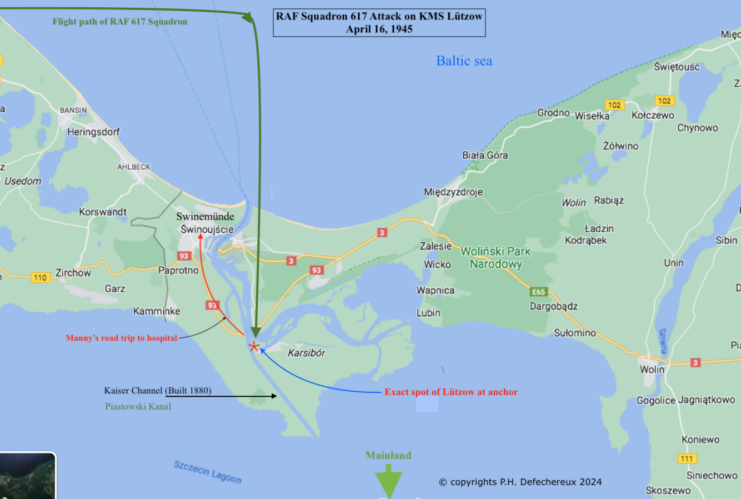

At 9:30 AM, a small motorboat took him across the canal to its west bank, where a Kübelwagen (the German equivalent of the Jeep) soon appeared across from his ship and stopped by the jetty. In two minutes, Emanuel von König was [in] the passenger seat, greeted by the driver. The latter quickly started on the short drive north, toward the port city of Swinnemünde, [along] the Swine river (Polish Świna) that empties into the Baltic Sea.

During that trip, both men had no choice but to revisit the damage inflicted five weeks earlier (March 12) by a massive US Eighth Air Force raid of over 370 [Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses]. That attack had resulted in serious destruction within Swinemünde and its surrounding area; three anchored merchant ships (used to ferry refugees), the wharfs, the riverside parks and the port city itself were hit.

Quite unfortunately, it also caused incomprehensible collateral damage. Several thousand German refugees from eastern Baltic ports [that had been] overtaken by the Red Army all along the coast had recently disembarked, [crowded] the parks or [were] still [aboard] the merchant ships.

The number of casualties among these desperate people in a zone presumed safe from carpet bombing was enormous. While the hospital that was Manny’s destination had remained intact, the ruined buildings visible in the landscape and the fresh memory of so many German deaths must have been sobering for both driver and passenger.

Why had the devastating air raid occurred?

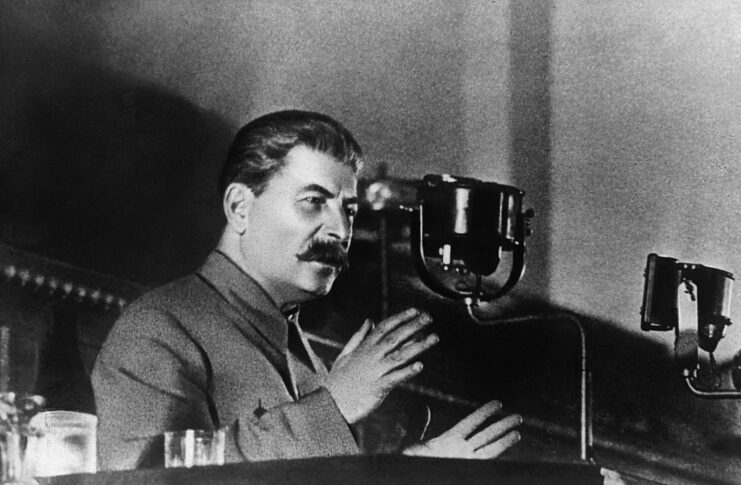

That raid had been the result of a pressing call by [Joseph Stalin] to his American allies, requesting a new and particularly hard hit on the port area of Swinnemünde.

The Soviet leader’s rationale was that this particular port was used frequently to resupply and re-provision the last remaining threats of the Kriegsmarine: Lützow, [her] sister ship Admiral Scheer and the slightly bigger Prinz Eugen, each equipped with batteries of highly destructive 11-inch guns that had been inflicting severe losses to Soviet tank brigades along the eastern Baltic coast since January.

With the final assault on Berlin due to begin soon from the starting line of the Oder river, they could seriously impede the Red Army’s massive attack on the [German] capital.

Whatever material damage the raid on March 12 had caused, the essential infrastructure had been quickly and sufficiently repaired by German crews to remain functional. None of the three German [warships] had been in port that day.

So when the KMS Lützow and Prinz Eugen docked at the port in early April, the replenishing with ammunitions and provisions was done in two days. After which, while Prinz Eugen stayed in port, Lützow’s captain was ordered to sail to a firing position some five miles further south and drop anchor at the entrance of the canal linking Swinemünde with the Stettin Lagoon (today Poland’s Szczecin Lagoon) – therefore, closer to the Red Army’s “tank highway to Berlin” on the mainland.

That spot was on the east bank by the village of Kaseburg (today Poland’s Karsibór), hence Emanuel von König having had to cross the canal by motorboat.

Emanuel von König undergoes surgery

By 10:00 AM sharp – punctuality being a near-genetic German trait – the driver dropped Emanuel von König in front of the hospital doors, through which he promptly walked.

We can imagine his minor surgery business following a standard procedure. After filling forms and submitting to an examination of his wound, he was taken to surgery and, once local anesthesia was administered, his wound was mended, after which he was sent to a quiet room to rest, recover and get some appropriate food.

At that moment, onboard Lützow, the mid-afternoon ambiance was almost festive. While the three long guns protruding from each of the ship’s two turrets kept dutifully firing on their inland targets, the special dinner was being prepared with gusto.

In the early afternoon, the [warship’s] radio operator had received word that a British bombing raid with fighter escort was on its way east, but that was not unusual. Several port cities all along the Baltic coast [that were] still in German hands had received visits from the [Royal Air Force] all the way to Königsberg, beyond the Vistula estuary. After the devastating US raid of March 12, their port of call was unlikely to be hit again – or so thought Lützow‘s officers.

This was, ironically, greatly underestimating the impact their ship and [her] two companion cruisers had inflicted on the Soviet westward advance since February. In fact, on or about April 8, Joseph Stalin was quite rankled by the news that Lützow and Prinz Eugen had just been spotted replenishing with ammunitions and provisions in Swinemünde.

Then, on April 11, he was told of the even more ominous repositioning of this nightmarish [warship] five miles further south, closer to the path of his tank brigades. “That ship must be sunk,” he vowed! But by whom? The all-powerful Soviet dictator knew he did not have the means, while the Americans had already been tapped once.

Then someone in the Stavka, a select group of Kremlin-dwelling senior military experts, reminded Stalin how the previous November his strange-bedfellow ally Winston Churchill had helped eliminate a similar threat beckoning both leaders.

Sinking of the German battleship KMS Tirpitz

The mighty 52,000-ton German battleship KMS Tirpitz had been hiding in a Norwegian fjord for months, posing a constant threat to British convoys loaded with Allied weapons [traveling] past the North Cape of Norway to the Soviet port of Murmansk, in the Barents Sea. The USSR could not win without massive Allied support.

After multiple failed attempts to sink the formidable threat in the previous six months, Winston Churchill agreed to unleash the ultimate British weapons system at his disposal: the special No. 617 Squadron RAF of The Dam Buster’s fame, made up of four-engined Avro Lancasters, but now uniquely modified to carry the phenomenal five-ton “Tallboy” bomb to get the job done.

On November 12, 1944, a formation of 32 special Lancasters had finally dispatched the mighty Tirpitz in a single raid. Two direct hits had, in minutes, caused the 823-foot battleship to capsize, drowning a majority of [her] estimated crew of 1,300 men.

The “Tallboy” was also aptly called the “earthquake bomb.” Its cataclysmic detonation created mightily destructive seismic waves in rapid succession, similar to those of a strong earthquake. Few man-made structures could resist such impact, even those made of steel-reinforced concrete.

Their huge success against Tirpitz had finally removed the biggest looming threat to Allied convoys on their way to Murmansk, to both leaders’ relief. Murmansk, situated east of Finland and north of the Arctic Circle, is the only northern Russian port that does not freeze in winter.

Joseph Stalin was preparing for his own ‘D-Day’

That is why, five months after that British triumph, Joseph Stalin faced the unpleasant task of asking Winston Churchill, again, for a difficult favor: would he, again, unleash the unique battleship-killing power of his No. 617 Squadron RAF, this time on Lützow? [The Soviet dictator] wished the job to be done “before the middle of April.”

This makes it clear how serious Lützow’s threat was to the Red Army, since [she] alone triggered serious concerns and tough decisions at the highest Allied level. The urgent timing part of the request was not an impatient add-on either.

Indeed, what even Churchill did not know then, nor General [Dwight D. Eisenhower] in Paris, let alone anybody in Berlin, is that Stalin had chosen April 16 as his own “D-Day” – the start of the massive assault on Berlin and all of East Germany. The Red Army forces would be overwhelming: 2.5 million men, 6,250 tanks and armored vehicles, 45,000 guns and four air armies. This had been decided the preceding December, based on long discussions with his generals and the Stavka.

Starting from bridgeheads already established all along the south to north flowing Oder river, the front would extend from Dresden in the south to Stettin in the north, a breadth of over 200 miles. Stalin also set the target date for the capture of central Berlin: April 22. That would prove a little optimistic, but not by much.

Winston Churchill agreed to Joseph Stalin’s request

Whatever arguments or false promises Joseph Stalin used, Winston Churchill agreed to the Soviet ruler’s request and promised a No. 617 Squadron RAF raid on April 13. Only he would send a smaller force than that used to sink the much bigger Tirpitz.

Thus, before sunrise on the promised day, a still-impressive special squadron of heavily-laden 24 Lancasters dutifully took off from their assigned airfield in Suffolk. Alas, eight hours later, when the group flying at 22,000 feet at last approached the Oder estuary, all they could see beneath them was an uninterrupted heavy cloud cover, making precision visual bombing impossible; they had no choice, but to turn back.

Another attempt was made on April 15, but this second raid was also aborted, this time even before reaching the Danish coast, because the weather over the target was, again, called mission-adverse. While the next day’s forecast looked safely more promising, by that afternoon it became known to the British – through their famous “Ultra” code breakers – that Prinz Eugen had left port.

The actual raid’s date would then correspond exactly with Stalin’s own “D-Day,” but the squadron’s size was reduced to 18 Lancasters, enough to destroy a single battle cruiser.

Attacking the KMS Lützow

At 4:45 PM on April 16, 1945, flying in perfect formation, this time at 15,000 feet in a clear blue sky over the western Baltic Sea, they soon caught sight of their prey in the distance. Squadron Leader R.M. Horsley then ordered his escorting [North American] P-51 Mustangs to return to base and leave them alone to execute their deadly business – no need to expose more aircraft to German flak, especially Kriegsmarine flak, renowned for the deadly accuracy of its gun crews.

Emanuel von Köning was one of those.

For this exclusive mission, 14 of the large bombers carried a “Tallboy” bomb, the other four [carrying] 12 explosive bombs weighing 1,000 pounds each. The next step of the mission was a planned deception for the crew of the targeted ship. The RAF raiders continued their straight eastward flight some 25 miles north of the coast, until they arrived nearly dead-north of the spot where the hapless Lützow was moored.

At that point, they effected a sharp 90-degree right turn to the south in perfect formation, three abreast in six rows. Now, they could aim straight for their suddenly obvious target, solidly anchored a mere 20 miles directly in front of their cockpits. The next task for the 18 pilots was just a matter of steadying their wide-spanned warplanes at the required attack speed, then let their highly-trained bombardiers call the bomb drop, intended to hit at exactly 5:00 PM.

Emanuel von König watched the attack from his hospital room

Emmanuel von König began to hear the first rumblings of the fiendish swarm from the hospital room where he was recovering. His earlier apprehension instantly turned into dread. Before joining the Kriegsmarine, he had spent the previous 16 months serving actively with land-based flak batteries – first around Munich, then in Prague, Czechoslovakia.

He could tell Allied aircraft types just by the noise of their engines. He ran out in horror to check what kind of mayhem was aimed at what target. These were British Lancasters!

As he watched the ominous formation approaching overhead in the bright sky, he did not see any bombs drop – at first. A storm of deep relief and high anxiety instantly burst inside his brain. Relief; the hospital from which he stared upward was safe. Dread; the enemy aircraft were going after “his” ship. Manny’s stomach tightened to the point of piercing pain.

By then, the crew of Lützow, having also heard the roar of the 72 mighty Merlin engines coming at them, had begun to panic. They all knew about Tirpitz and [her] drowned sailors.

Manning their posts aboard the KMS Lützow

Their “special dinner” instantly forgotten, the flak gunners ran to their turrets. One crew found success almost instantly; a Lancaster from the first row of three was hit on close approach directly amidship.

Its left wing instantly caught fire, then quickly folded. It went down fast. Leaving behind a dark trail of smoke, the large bomber exploded in a massive ball of flames inside the Kaseburg woods, not far from Lützow’s starboard side. Fatefully, it would be the last Lancaster to be shot down before the war ended.

By now, all the bombs were in mid-air, on their way to the target, while the 17 remaining Lancasters, already beyond reach, were about to veer quietly 90 degrees westward. There [were] very little Luftwaffe [aircraft] left for them to fear on the way back to eastern England – one more eight-hour flight, [and] the sixth in just four days for No. 617 Squadron RAF on the same mission!

Reports that the heavy cruiser had been lost

Emanuel von König, having witnessed the first flak success with a degree of hope, had his early optimism quickly punctured as he watched the British bombers turn away. From the detonations, he could tell the British bombs had really hit hard, even though no funereal black column of smoke had appeared, other than the one created by the downed RAF bomber.

About a half hour later, the medical staff had heard by telephone [that] Lützow had sunk into the channel. That was rushed, unverified information. It was finite enough, [however], for Manny’s future as a fighting sailor. This was a duty he had dreamed of since [the] age [of] 10. He had, by now, heartily fulfilled it for a mere four months. What was going to happen to him next?

The morning after the raid, Kriegsmarine officials in Swinemünde were officially informed that Lützow, further south, was “wrecked.” We will find out later that the post-bombing fate of [the ship] proved far less “final” to [her] mission than at first imagined. Meanwhile, based on current information, there was Manny without a ship to serve on.

Local officials did not hesitate long about where to send him next.

Emanuel von König was to be sent to Berlin

Only days earlier, they had received a formal order from [the Führer‘s] bunker in Berlin. In fierce language, [he] had declared all of the the [regime’s] still-free cities must be turned into “fortresses,” to be defended to the last – foremost came Berlin, of course.

The head of the Kriegsmarine, Großadmiral Karl Dönitz, also in the bunker at that time, had been quick to offer his leader any able-bodied sailors not essential to what little remained of naval operations, to be reassigned and moved to the defense of Berlin. Always eager to please [the Führer], he promised up to 20,000 men. That order had been quickly forwarded to all Kriegsmarine offices still functioning.

So it happened that Emanuel von König, early on April 17, barely a month into his 18th year, became one of the “non-essential” sailors available to his Führer. By now, he surely was able-bodied, having reached a not yet final height of six feet, and been richly fed and intensely exercised by his job on Lützow for the past four months. In addition, as a fully indoctrinated “Youth,” he still believed in the Führer’s strategic genius. Having sworn a personal oath to him, he would determinedly follow his next orders.

When, in the spring of 1937, having just turned 10, he had been inducted by state law into the junior level of the Youth [organization], he and his entire age group from all [of] Germany were first prompted to take a solemn oath to their absolute leader.

In front of their senior local members, right hand raised, they willingly recited these words, “I swear to devote all my energies and strengths to the savior of our country, [the Führer]. I am willing and ready to give up my life for him. So help me God.” Parents had no say in their children joining. There was a separate organization for girls. Objecting to the authorities carried severe risks, even the possibility of being sent to a camp.

From then on, and until age 17, Manny had, on frequent occasions, assimilated plenty of paramilitary training and propaganda disinformation in equal dosage, mostly on weekends away from home. From July 1943 onward, he had served proudly and heartily in flak units defending the [regime] against constant Allied mass-formation bombing runs. He was never seriously wounded, while gaining extensive experience with gunnery practice and integrating military discipline.

Assigned to the western suburbs of Berlin

As a result, on the day of the RAF raid on his warship was mistakenly reported, Emanuel von König followed his transfer orders to an infantry division defending Berlin without question, thoroughly unaware that the [regime’s] capital city was about to become a lethal cauldron from hell, defended by overstretched Wehrmacht units attacked from all cardinal directions.

Yet, from the start, his remarkable good fortune came into play again. Young Manny was assigned to a Wehrmacht division located in the western suburbs of Berlin. That sector would end up being the relatively quietest within the giant pincers of the enormous Soviet assault.

By geographic necessity, in executing its envelopment of [Germany’s] capital, the Red Army was attacking from the east. As a result, its planned grand assault prioritized the seizure of the eastern, northern and southern suburbs. Next would come pouncing inside the [city’s] vital center, where the most-prized and, therefore, [the] most heavily defended targets stood: the Chancellery and [the Führer‘s] bunker.

Those were naturally the areas where the fiercest house-to-house [engagements] were expected to take place.

Taking a train to Berlin

Understandably, then, the western suburbs would be attacked last, and with exhausted fury. That is precisely where Emanuel von König was sent, as told in his 2005 recollections. Studying a map, his train itinerary from Swinemünde was likely directed first for the town of Neustrelitz, in the state of Mecklenburg, some 60 miles southwest of its starting point by the Oder estuary and almost straight north the same distance from Berlin.

His had most likely been a slow ride, as plentiful strafing Russian aircrafts were prone to attack any convoys. By the time his train reached that town, possibly on April 19, the enormity of [the] Red Army offensive was, at last, becoming clear to the German field generals subjected to it, even if not yet to [the Führer] himself. It is, therefore, likely that his train was rerouted further southwest from that first stop.

Across the open plains of the state of Brandenburg, Manny and his cohort of young sailors (soon-to-be-infantrymen) eventually disembarked in the region of Nauen, in that same state.

This ancient town, located on the main road crossing Germany from east to west, stands 24 miles due west from Berlin and 17 miles northwest of Potsdam. Within a close radius from its central square, 14 small farming villages are scattered around the rich plain. This matches well with Manny’s recollected description of the area where he took his own last stand. That would have placed him with the the German 12th Army, led by General der Panzertruppe Walther Wenck and still relatively functional.

A clear-minded leader, Wenck would become one of only three generals who would shortly deny desperate final orders from their Führer during the last week of his life. Those three were seeing with their own eyes the dreadful reality surrounding them only too clearly to feel obliged to heed the phantasmagoric orders still issuing from the famous bunker.

The Führer himself, now well ensconced inside it, was protected from knowing how bad the news was by his fawning senior generals and his own delusions. The latter were not new, only much worse than ever before.

Four months earlier, when warned by a well-informed official German Intelligence report revealing that a massive assembly of Red Army forces along the length of the Vistula river signaled a pending major Soviet offensive, [he] had instantly discounted that information as “the greatest imposture since Genghis-Khan!”

The Soviet Red Army outnumbered its German foe

By late April, when the predicted Soviet assault had succeeded [in] crushing all defending German forces on the far Eastern Front and advanced 200 miles westward to reach the Oder river, the Führer’s mind had turned ostensibly further away from the dreadful reality in the field. In no way could he and his senior staff envision that the Soviet forces attacking Berlin, now from much closer, outnumbered their German foes approximately 11 to one in infantry, seven to one in tanks and 20 to one in artillery.

Their quest for revenge for the atrocities the [Germans] had committed in Russia was heinous. No quarters would be given.

Emanuel von König’s chances of survival in these last weeks of April 1945, were, therefore, slim, even in the somewhat quieter sector in which he had just arrived. By April 20, all remaining German forces around the capital city found themselves severely depleted in manpower, weaponry and munitions.

Their commander-in-chief fiercely remained in complete denial not only of the stupefying superiority of assaulting Soviet forces, but also of the capacity of his remaining shredded Army units to stage breakthrough counter-attacks. His only correct insight on that day was that the fighting spirit of nearly all German defenders was still strong and committed. This would only last for about another week.

Remembering Emanuel von König’s trip to the KMS Lützow

Emanuel von König left no records of his thoughts during the presumably harrowing train ride that brought him to his assigned infantry brigade near Nauen. One can, however, make a safe guess, based on an earlier train ride he experienced during the four days bridging the end of 1944 with the beginning of of 1945.

That ride had started on December 30, 1944, from Mürwik-Flensburg (western Baltic), home of the Kriegsmarine Naval Academy from which Manny and dozens of like-minded young students had just graduated; its destination was the important military port of Pillau (today Russia’s Baltiysk), on a long spit of land just outside the Vistula river’s estuary.

In that very port, Manny and his fellow graduates would, for the first time in their lives, board a fighting [warship] awaiting them as [her] replacement crew: the KMS Lützow.

The total distance of the railroad trip being about 800 miles, it would, under peaceful circumstances, take a German train less than 10 hours to cover it. Instead, wrote Manny in 2005, “It took us four days. Many stops, much retracing and finding new routes to avoid contact with advancing Russian troops. Several times strafed by Russian aircraft, casualties. Many times within range of Russian artillery.”

The survivors boarded Lützow on January 2, 1945, welcomed by their newly assigned skipper, Kapitän Heinrich Knoke.

A mere 100 days later, with his seaman’s career now well behind him, the train ride to the west of Berlin must surely have been as calamitous. As in his earlier ride to rejoin Lützow, Manny most likely also lost several comrades who would never make it to the enormous battlefield surrounding Berlin. But he did.

Emanuel von König’s family must have been worried

What we also know is that, by the time he got to his newly assigned infantry unit near Nauen, probably late on April 20, Emanuel von König was still wearing his navy-blue uniform. It did not matter in the least to the lieutenant [who] greeted him. Any extra man was welcome, especially one looking healthy, well-fed and [standing] six-foot tall.

Would his luck hold in the titanic battle the whole world was following?

Ironically, in Munich, at this very moment, Manny’s mother and sister still knew very little about the fate of the two men who had long been indivisible units of the von König family: Ludwig, husband/father, and Manny, son/brother.

The level of worry for both women was acute. From a friend who dared listen to a Swiss radio station – under penalty of execution, if caught – they had just learned that Lützow had been “sunk in the Oder estuary.” Nothing more specific. Might Manny have survived? As to Vati, they had last heard that he was stationed on the barrier island of Sylt, just off the east coast of the lower Danish peninsula – seemingly a quiet place, but who could tell how safe in these days of despairingly stunning upheavals?

Yet, even then, Wolfhilde still held a strong faith in her Führer. In a diary entry entered on the likely day her brother joined the infantry “to defend Berlin,” she wrote:

“Munich, April 20, 1945

“Today is the Führer’s 56th birthday. Today, in the tensest of times, we all think of him. It is he who had led us imperturbably and steadfastly, faithful and true through three hard years of wars and who will continue to lead us forward. May he keep his strength and good health and be able to ward off any challenges.”

The disconnect between the deep faith of his mesmerized devotees who had been deceived by enormous lies for over a decade in order to stay inarguably committed to the cause and the reality of the state of their idol in the bunker was never so vast. In the violent autocracy where individual rights had been eliminated since 1933, such fanaticism was bound to meet a catastrophic end.

What really happened to the KMS Lützow after the RAF raid?

As described earlier, the British crews on duty inside each Lancaster during the April 16 attack against Lützow had experienced two lengthy round-trip flights to and from the target in the previous three days. Both attacks were aborted, due to unfavorable weather conditions.

When the weather finally cleared for a third attempt on the 16th, the aircraft crews, including the bombardiers under the cockpit, faced yet another eight-hour flight before reaching Swinemünde. Fatigue must have been a serious factor, indeed. Of the 13 “Tallboy” bombs dropped, only one struck close enough to the moored German [warship] to inflict grievous damage.

All the others went wide. Of the forty-eight 1,000-pound bombs, only three hit Lützow’s main deck. Of those, two were duds – not the bombardiers’ fault – so that only one caused serious damage! That bomb exploded on or near the large front turret, putting it out of action.

How damaged was the KMS Lützow?

The most devastating destruction was caused by the lone “Tallboy” that came very close to hitting the hull mid-ship on the starboard side. It struck right between the bank and the ship, plunging inside the narrow channel of water between the two before exploding with enormous brutality. While the “earthquake” effects of the bomb did their job on the thick armor, they could not match what a direct hit would have, [which was] destroying much of Lützow’s superstructure.

This near-miss would prove critical and allow Lützow and [her] final crew of just 200 Kriegsmarine volunteers to have their last hurrah.

What the huge bomb did achieve was splitting the starboard side of the hull longitudinally over a length of about 60 feet. At sea, this would have immediately been fatal, but the targeted ship was moored in a shallow canal, only about 16 feet deep, whereas the draft was 23 feet.

So Lützow did “sink,” but soon settled on the seafloor, [her] main deck almost seven feet above the water’s surface!

From warship to stationary gun platform

While no longer navigable, [she] could still be used as a stationary gun platform and remain effective. All depended on damage assessment the next morning by Kapitän Heinrich Knoke and crew. No wonder the German officials at Swinemünde drew the wrong conclusion.

For the rest of his life, Emanuel von König would never know of that long ending, nor how bravely his beloved [warship] fought on to the last.

On the morning of April 17, as our feisty young sailor was oddly reassigned to the Battle of Berlin, the volunteer crew of about 200 men, under the command of their kapitän, managed to steady the ship using bilge pumps to even out the ballasts. Next, his men made electric repairs, allowing the rear turret and its three 11-inch barrels, as well as some of the six-inch twin guns and a few [anti-aircraft] stations, to be operational again.

By the next day, loud booms marked the moment the big guns started firing again, completely surprising and thoroughly scaring the Russian tank crews approaching in the distance.

The fanatical unit remaining aboard Lützow would keep firing their still-capable guns on Soviet targets until the evening of May 3, when they ran out of ammunition. At that point, with Soviet tank brigades now approaching the right bank of the Swine river from the north, they quickly proceeded to implement the pre-arranged final act: fully destroying the ship before capture by means of high-explosive charges.

But the brave [warship] would give them a hard time. The harried men quickly ran into technical problems, accidentally starting a fire, which caused the charges to explode without serious harm to their vessel. The remaining men then fled to shore midday on May 4, lest they become Soviet prisoners of war (POWs).

The Red Army soon captured what was left of [the] now helpless Lützow, four days before Germany surrendered to the Allied forces on May 8.

Detailing the final days of the KMS Lützow

What exactly happened after that to the “battleship that wouldn’t die” remained murky and contested for years.

When the relevant Soviet archives became accessible early in the current century, Lützow’s story could, at last, be completed. That tale [was] first recreated by three historians, and, more recently, in [a] very thoroughly detailed article of over 33 color-illustrated pages by the French Navy magazine, LOS! (March-April 2019, Issue #43). It adds more surprises to the saga.

The Soviet authorities, after paying little heed to the ship resting on the seafloor of the “Kaiser Way” – soon renamed [the] Piast Canal by the Poles – ordered in early June 1947 that the rusty hulk of Lützow be re-floated. This took an enormous amount of work, beginning with [an] elaborate underwater sealing of the hull’s many breaches, then the lengthy use of powerful pumps to expel thousands of tons of sea water from the ship back into the canal. It took weeks.

Once the fateful [warship] was re-floated, the same authorities ordered that [she] be packed with a large number of high explosive ordnance, seemingly “borrowed” from the RAF at [the] war’s end. At least three 1,000 pound- and two 500-pound bombs were placed around [her] deck, all connected to a master switch.

At last, on July 20, Lützow’s hull was then painstakingly towed a dozen miles out from port and into the Baltic sea. The “drag factor” of the heavy hull was such that the powerful icebreaker Wollynets had been called to do the job. It took two days to get Lützow in the right spot, officially at 8:25 AM of July 22.

After one more inspection, Soviet naval officials finally and ignominiously ordered the triggering of the multiple explosive devices. Several explosions were heard, causing damage and a loud and fiery show. To everyone’s embarrassed and stunning surprise, however, “the battleship that would not die,” once more failed to slink below sea level! Several bombs had failed to explode!

After a reset of connections, a second attempt was made at 12:45 PM. One 1,000-pounder positioned upper mid-ship exploded, causing terrible damage to the superstructure, without affecting [her] float-ability. Emanuel von König would have been proud!

The officials in charge then decided to take more drastic measures. The water pumps were to be removed, while all the reserve ordnance was to be used for the third try. As extra insurance against another miss, a 1,000-pound bomb was to be placed on the rear deck. After an unknown number of [the] Soviets in charge of this operation were removed, if not shot, a contingent of highly stressed survivors gratefully skipped lunch and dutifully executed the new orders.

The new set up was declared “ready for final use” by mid-afternoon. The third command to “fire the charges” came at around 4:23 PM. Hundreds of hearts from the assembly of men in charge were likely pounding with high anxiety.

This time, to their immense relief, it was the coup de grâce; the first German [warship] built post-World War I finally disappeared under the waves by 4:24 PM, local time. Since then, [she] has laid on the sea floor, 370 feet down.

Coming to conclusions

One obvious question comes to mind here: why [wasn’t] a submarine used to accomplish this task, instead? Two torpedoes would surely have destroyed the patched-up hull in an instant. We will leave the answer to this puzzle to dedicated Sovietologists.

This rambunctious finale makes a few things clear that still resonate loudly today. First, the Soviets [were] masters of botching what would be simple operations for most militaries. They only succeeded when operating in giant masses, from which they’d tolerate unspeakably heavy losses.

Second, their “all powerful leaders” actually [had] such weak self-confidence that they thoroughly [erased] all traces of their failures, when such happened, which they often [did]. Joseph Stalin obviously felt greatly embarrassed by the serious slowing effect Lützow’s bombardments had caused to [the] advancing armies during their first rush into the northern frontiers from February to April 16, 1945.

He, therefore. could not tolerate the remaining presence, even of [her] hull, in Polish waters near the Baltic coast after the war ended. He ordered the enormous expense of re-floating the ship, only so he could have [her] sunk deep into the Baltic Sea, never to be seen again.

KMS Lützow‘s history

Lützow was a worthy scarecrow. Originally christened Deutschland, the [warship] made [her] maiden voyage in May 1933, four months after the Führer was named chancellor of Germany.

In mid-November 1939, as the ship was in in [her] homeport of Kiel for a brief refitting, he and Generaladmiral Erich Raeder, made the decision to change [her] name. Their motivation for such a change was principally to avoid humiliation, in case the Allies succeeded in sinking a ship carrying their nation’s name.

As a replacement, they chose that of a Prussian general who had become famous for his highly-effective leadership of volunteer groups – Freikorps – during the Napoleonic Wars: Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm von Lützow (1792-1834).

Remembering the KMS Lützow

Most notably, “the battleship that wouldn’t die” still causes noise in the 21st century.

On the island of Karsibór, a museum stands today to memorialize the crew of the Lancaster that was shot down, who died fighting the German foe. The main memorial is a flowerbed from which the bomber’s wingtip carrying the British tricolor roundel proudly emerges.

In October of 2020, while conducting dredging work in the Piast Canal and, to their wary stupefaction, a Polish crew discovered an unexploded “Tallboy” bomb near the canal’s bank. The state quickly called an emergency that led to the evacuation of almost 1,000 civilians.

More from us: Phantom: The Innovative and Unique Self-Propelled Concrete Tank Vessel

A remote deactivation attempt occurred, resulting in the massive bomb finally exploding! Such good precautions had been taken that not a single person was hurt.

Philippe Defechereux earned a Masters Degree in Business from Manhattan’s Columbia University in 1972. Over the next 25 years, he became a successful New York and Detroit advertising executive, a published author in both English and French, a History buff and a car racing fan.

In the mid-1990s, he decided to try his hand at authoring his first book. He opted to focus on the history of car racing. His first opus would be devoted to the birth of European road racing in America after World War II. That first book came out in 1998.

It quickly sold out its run and generated acclaim from racing clubs and veterans. So strong was its halo that it got the attention of automotive publisher Dalton Watson Fine Books. In 2011, a much enhanced and expanded second edition came out, retitled, Watkins Glen 1948-1952 – Glory, Drama and the Birth of American Road Racing.