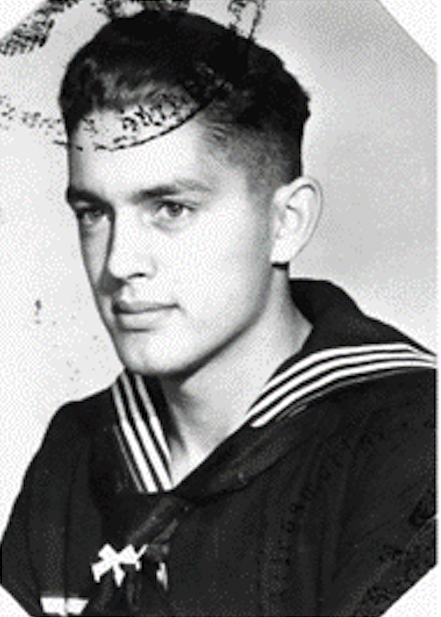

Here, we continue our eventful World War II story of Emanuel von König, when he arrives in the western suburbs of Berlin on April 20, 1945. He was sent there to defend his Führer and the German capital after the heavy cruiser Lützow, to which he had been assigned early in the year, was (falsely) considered lost to a Royal Air Force (RAF) raid of 18 heavy bombers.

Still wearing his Kriegsmarine blues, von König was attached as an infantryman to the northern brigades of the Wehrmacht’s 12th Army.

Emanuel von König joins the Battle of Berlin

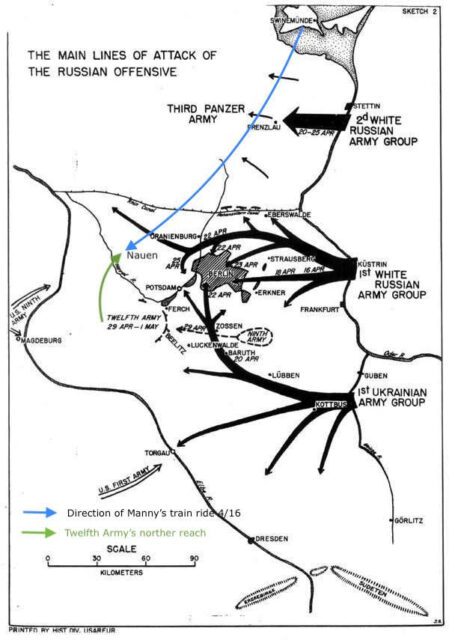

On the afternoon April 20, 1945, Emanuel von König joined General der Panzertruppe Walther Wenck‘s 12th Army northern detachment near Nauen, west of Berlin, after a long southwesterly train ride that had begun near the coast of the Baltic Sea.

Wenck’s was the only German Army left in marginally good shape (much better than the others). The reason was that, before the Red Army attacked, the 12th Army had purposely been positioned furthest west, close to the eastern banks of the Elbe, to defend against the advancing western Allies. In fact, Wenck’s troops had already taken a beating by the powerful pincer emerging from the across the Rhine.

His area of responsibility was vast, stretching all the way to Nauen.

Panic breaks out in the Führerbunker

Two days later, on April 22, 1945, the Führer absorbed two more pieces of news during a high-level midday conference with his staff. First, he had to admit that a (hopeless from the start) counterattack from the north he’d ordered the previous day had not, in fact, taken place. Second, and in a bold contrast, he learned the Red Army had breached the perimeter of Berlin from that very same cardinal direction.

These crushing updates caused him to burst into a loud fit of rage as never before witnessed, ranting, among other things, about being betrayed by both the Wehrmacht and the SS. He then recognized to his men for the first time that the war was lost. The shockwaves of that admission instantly hit everyone in the room. The Führer then added that he’d remain in the bunker until the time came. Everybody else present could leave as they chose.

Finally, he ended his tantrum by saying that, since he was too old and weak to fight, he would end his life in the bunker, so as to never be grabbed by the Soviets; the wheel of history had just completed a full turn. This news, except his decision to remain in Berlin, wasn’t broadcast by the regime’s propaganda machine; it was kept a tight secret.

Later that afternoon, then somewhat calmed down, the Führer endorsed a new delusional suggestion made by Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, issuing an order for Walther Wenck to turn his 12th Army around immediately and rush northeast expeditiously to “save Berlin.”

This was one more display of full denial in the face of the enormous power of the vast and well-equipped Red Army force aligned around his capital city and aimed at the bunker, in particular. Wenck knew he didn’t stand a chance, but to make sure this order would be followed, the Führer asked that Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel, another pliable sycophant, make a visit Wenck’s headquarters the next morning and emphasize the critical and urgent nature of his order.

Emanuel von König was already thrust into the chaos

On that same dramatic day, Emanuel von König and his small infantry unit, having no idea of the desperate shenanigans going on between generals in the field and their waning Führer in his bunker, were confronted with the chaos the latter still stubbornly refused to acknowledge. He recalled in 2005 (text slightly modified for chronological clarity):

“A few days after joining my unit, we were on patrol and stopped for a short rest in a wooded area. I noticed the body of a dead German soldier, lying face down. Since we were short on ammo and food, I went on to inspect his knapsack. No ammo but a piece of sausage and a pair of red and black knitted mittens. Since the nights were still pretty cold, I kept the mittens – and shared the sausage.

“The next day [April 23rd] we held a position along a ridge and were strung out relatively thin. In the late afternoon, our unit was apparently pulled back – but the order did not reach us at the end of the line. It became dark and there was the four of us, isolated. From our location we could see a few burning farm houses, and they were giving enough light to be able to see Russian columns moving along a road.

“We decided on the direction to go and after a few hours, we came to an abandoned village. We were exhausted, went to a farm house, went upstairs and found a place to sleep.”

Red Army troops close in on the 12th Army’s position

They were in the vicinity of Nauen, Germany, which was also the site of a major National Socialist German Workers’ Party radio transmission station broadcasting to the rest of the country. The farming town was captured by the Soviets later that day.

With Nauen taken, April 24, 1945, marked the formal completion of the Red Army’s encirclement of greater Berlin. Emanuel von König continued his story on what was certainly the morning of that compelling day:

“What woke us up in the morning was the unmistakable sound of moving tracks. Then it suddenly dawned on us that there was no German armor anywhere near. Russian tanks and infantry were moving through the village and we noticed patrols working their way down the road going from house to house. It was not long before one entered the house we were in.

“We heard, in German, the question if there was anybody there? I answered: Yes. How many? Four. Come down with your hands up. I learned from experience that in confrontation, it is best to project a very positive attitude and positive thoughts.”

Of note here, von König had just recently turned 18 at that dramatic life-and-death moment. He continued:

“I was the first one and as I came around the landing to the staircase, at the bottom of the stairs were three Russian soldiers with three machine guns pointing at my belly. All went well. They treated us kindly and even shared some food. We were taken to a collection point which was the fenced-in yard of a farm. During the day, more prisoners were brought in.”

Discovering the miseries of being a prisoner of war (POW)

The best way to describe what happened next is through Emanuel von König’s own words:

“Late afternoon, we were taken to the back of the barn. Standing there were a Russian soldier and a [servile] German officer. His first order was for me to turn over any valuables – coins, wristwatch, rings and any other jewelry.

“When I opened my knapsack, the the Russian became very agitated and released the safety catch on his rifle. The officer told him to calm down and asked me how I came to have the mittens. It turned out that they were Russian Army-issue. After I explained how I got them and this was explained to the Russian, the safety went back on. Of course he kept the mittens.

“The next morning, we started marching and during the day the ranks of our column swelled. At about noon, we had a short break. We were allowed to drink from a creek that was adjacent to the road. We all flopped down to fill up on water. When I had enough, I looked up on the other side of the creek, I saw the bloated bodies of two dead cows in the water. Too late to worry.

“A few hours later, we came to a small village. There was a knoll with a number of Russians standing around. We were ordered into a single file formation and led to a spot where there were many baskets full of scissors; anything from nail scissors to garden shears. A Russian would call two of us, take the next scissors and go through the game of pointing motions meaning ‘cut each others’ hair. We recognized that this was the beginning of a delousing operation.

“To one side were picnic tables staffed by mean-looking Russian women soldiers. Once sheared, we had to strip, put our clothing in a net-type bag and submit to being sudsed and close-shaved over every part of our body. Then into a mobile unit to be sprayed with some awful-smelling stuff, followed by a cold shower. We spent the night in a fenced field.”

Emanuel von König’s first interrogation by a Soviet officer

Emanuel von König wrote about what came next:

“The next morning, I was called by name to be taken to interrogation. I wondered how they knew my name and then I noticed all my papers were gone. I was still in Navy Blues and I figured that because of that they wanted to take a closer look at me. I was taken into a house where, behind a table in the interrogation room, sat a Russian officer.

“He spoke perfect German: ‘Sit down, your name is Emanuel von König?’ ‘Yes, Sir.’ ‘The von in your name indicates nobility; therefore, your father is a Junker and Junkers have large land holdings. What I want to know from you right now is where those holdings are located.’ ‘My father works for the State Railroad. He is a surveyor. We live in a rented apartment in Munich and I have never heard of any properties.’

“He changed the subject for a while and then came back to the same question. I gave the same answer. He then advised me of the penalties for lying to an interrogating officer. He repeated the question; I gave the same answer. Then he made me an offer: ‘We will take you behind the German lines. If you can convince some German soldiers to surrender and come back with you, we will release you and you can go home.’ I saw that as just two more chances to get shot. I declined.

“Then, more questions. This went on for about 20 minutes before he handed me my papers and terminated the interview. At the door, I was reprimanded because I had not saluted the officer upon departure.

“I rejoined the column of prisoners and the next afternoon, we arrived at our first camp. Inside a large fenced-in area, several very large storage sheds became our quarters. The place must have been some commercial enterprise. In the building were some low platforms for storing something. There was no straw and we slept on the wood.”

German soldiers held in Soviet prisoner of war (POW) camps

Emanuel von König went on explain the Machiavellian cascading methodology driving the Soviet prison camp assignments in the summer of 1945. He wrote:

“The system in the Russian camp administration was such that if you became sufficiently ill you were transferred to another camp which had only ill people.“

He next described the regime he faced in the first camp at which he’d just arrived, only three days after his early morning capture, with these words:

“The food was terrible. Once a day, some thin soup, thickened with some starch and floating around were some kernels of barley. The bread was awful, very black and the center not baked though. It was not very long before I, among others, developed problems with stomach and intestines.”

He was soon moved to a second camp, ‘one with only sick people.'” He then wrote:

“In the first of such camps I got the upper bunk and I noticed the wall smeared with blood. Squashed bedbugs!“

In a gloomy new kind of Russian roulette, the methodology indeed dictated the next turn. von König recalled:

“As my situation deteriorated I was moved again to another camp. It had buildings with three stories and I learned that each building housed prisoners who had different infectious diseases. My building was for non-infectious people like me, but even so, the death rate was appreciable. We slept on straw on the floor next to each other. On some mornings you would wake up and find that your neighbor had died during the night.“

A strong spirit was needed for Emanuel von König to survive

Under the circumstances, Emanuel von König’s following sentence is simply amazing:

“The idea that I could die never occurred to me. I was no longer in combat and there were no longer any bullets which had my name on them.”

By the time that life-sustaining reflection crossed his mind, the calendar must have approached mid-May. The war was over in Europe after a final push of maneuvers contemporaneous with mass-“everything:” -destruction, -starvation, vile betrayals, assaults and worse. von König couldn’t have had any inkling of the infernal situation in which his beloved Vaterland found itself; for the better, as his own predicament was hard enough to bear.

Now is a good time to recall key moments that took place in Germany, further enlightened on by the war diary kept by von König’s sister, Wolfhilde, in Munich. We’ll start at dawn on April 23, 1945, the day he and three fellow soldiers lost contact with their unit, eventually taking refuge in a farm at dusk.

Twilight of the Gods starts to set in Berlin

On the morning of April 23, 1945, Wilhelm Keitel, having been present during the Führer’s moment of utter despair, followed by deadly fatalism the previous afternoon, dutifully appeared by train at Walther Wenck’s 12th Army headquarters. Delivered in a woodsy area southwest of Berlin, his speech was standard, cold, mindless and threatening fare, fully detached from the facts on the ground.

After Keitel’s departure, Wenck and his staff, realizing the utter unreality reigning in the Führerbunker, decided, instead, to turn their force around, straight toward the east, in order to rescue the German 9th Army caught south of Berlin. “It’s not about Berlin anymore, it’s not about the [regime] anymore,” Wenck told his troops.

Saving their fellow soldiers and the thousands of civilians accompanying them was the more noble and achievable task.

Western and Eastern Allies shake hands at the Elbe

On April 24, 1945, Walther Wenck’s 12th Army thus duly began to turn 180 degrees east, flaunting the Führer’s’ direct order, and left Berlin to its inevitable fate, which, at any rate, he could never have “saved.” His troops executed the turn with an enthusiasm they hadn’t felt for a very long time.

Emanuel von König and the three soldiers with him couldn’t be part of this; they’d just been captured by Soviet infantrymen.

On April 25, Soviet and American troops famously shook hands for the first time at the town of Torgau, on the higher Elbe. What was left of the German regime, already amputated forever from its large eastern states (East Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia) was now pitifully also divided in two: northern and southern regions.

On April 26, Tempelhof Airport, closest to central Berlin, was finally captured by the Red Army, after a days-long battle. Escape by aircraft for the German top brass – besieged Berliners called them “the golden pheasants” – stopped being an option. Joseph Stalin was relieved when he heard the news; he’d dearly wished to capture as many of those “pheasants” as possible.

American troops capture Munich

On April 28, 1945, the American forces much further south closed in on Munich. Emanuel von König’s sister wrote in her war diary on this date:

“Munich is becoming more and more a frontline city. The Fronts close in. The food and clothing warehouses are being disbanded, with all materials being distributed. […] We wait to see what time will bring.”

The dismantlement of the Führer’s state was proceeding countrywide, only 12 years after it began. He’d vowed it would last 1,000 years. The next day, April 29, Wolfhilde went further in her war diary, writing:

“I sit here writing as the earth shudders from the thunder of gunfire. They [the Americans] are thought to be in Ismaning already. One volley after the other is shot through the barrels. In between, one feels the detonations of the bombs. It is all so unique.

“Another hit. Each one seems to be closer. The street cars continue to run; the traffic goes on in the frontline city of Munich. What must Vati and Manny be thinking? For weeks we have not received any news from them. […] I want to know how the Führer is doing. Is everything supposed to be over, everything we believed in and everything that we lived for? Should all the sacrifices have been in vain? I cannot believe it.”

This was the beginning of the self-pity that a great majority of Germans were increasingly expressing. That same day, Dachau, just north of Munich, was liberated.

Portraying the Führer‘s death as ‘heroic’

On April 30, 1945, in the early afternoon, the Führer took his own life in his bunker, as did his mistress-recently-turned-wife, Eva Braun. Before that final act, he had nominated as his successor Großadmiral Karl Dönitz. Other leading henchmen had long lost his trust.

Dönitz, on May 1, made the solemn public announcement at 9:30 PM. Preceded by appropriately somber Wagner pieces of music, a male voice announced: “It is reported from the Führer’s headquarters that our Führer, fighting to the last breath against Bolshevism, fell for Germany this afternoon in his operational headquarters in the [regime] Chancellery. On April 30, the Führer appointed Admiral Dönitz as his successor.”

More lies, even then. Dönitz then went on, expressing his grief and outlining his plans for the future – whatever of it he had left.

On that same day, but before the formal radio announcement, Wolfhilde von König wrote these words in her war diary:

“Memories of the past hold me prisoner. May 1st is National Day of the German people. Those times will probably never return. In the city [Munich], all the stores are being looted by the rabble. […] The enemy tanks and vehicles roll unceasingly through our city. They are made of such poor material that one cannot believe we had to capitulate before these weapons.”

She was describing the 3rd Brigade, 157th Infantry Regiment, US 45th Infantry Division, commanded by Lt. Col. Felix Sparks. The 45th had fought from the beaches of Normandy almost one year earlier, all the way into Bavaria. Their winning equipment was the best America had produced.

Both von König men are still missing in action (MIA)

In a May 2, 1945, war diary entry, as well as in 49 further entries Wolfhilde von König later wrote, she never once mentioned, let alone commented, on the Führer’s death and how it affected her. The “strong man” who’d guided her life and dazzled her mind over the previous 12 years no longer deserved any ink.

Meanwhile, she and her mother still had no idea what fate the two men they loved had met. It was best they didn’t know Emanuel was still a captive of firm Soviet hands and in declining health. He, of course, knew nothing about any of these cataclysmic events. All he could do was to keep his indomitable faith in his survival.

It would be put to more tests. He wrote in 2005:

“I had one more camp transfer. I was in Poland [actually western Czechoslovakia] not too far from the German border. In this camp, once a week, there was a lineup of those prisoners where it was questionable whether or not they [would] make it to next week.

“If the judgment was a NO, the prisoner received his release papers, a railroad ticket to his hometown, a piece of sausage and one and a half loaf of bread. Once you walked through the gate of the camp, you were considered a free man and the Russians could care less what happened to you then. You were no longer their problem. If you died, the locals had to bury you.”

One would think that maintaining a life-positive attitude in those circumstances was an impossible act of will. von König doesn’t say, but somewhere in his mind might have been the sense that fate would once more favor him. We will never know, but how his life story unfolded next is genuinely astounding.

Fate and Lady Luck come together to grant a longer life

Emanuel von König wrote about what happened next:

“One week it was my turn in the lineup. We had little tags and a description of what was wrong. The person who made the inspection that day was a German Army Doctor, also a prisoner. When he came to me he looked at my name and started asking a few questions.

“It turned out that he and my father, at the beginning of the war, served in the same unit and used to play cards together. I will never forget his last words to me; ‘Son, I will never get out of here, but you will.’

“He signed me off and I was released. Thank you, God. It was early July, 1945.”

Now, all he had to do was to make his way home through a ravaged, defeated country, whose remaining eastern states were quickly passing under Soviet control. It would take a lot longer than he probably imagined after the brief thrill of his release.

Meanwhile, in Munich, there’d come some some reflections in the von Königs’ apartment. Wolfhilde’s war diary tells us her thoughts on May 12, 1945:

“For three days now there is peace in Europe. Peace? Like a mockery it rings in our ears. In America and England, the bells resound for a victory that, even according to Churchill was won continuously though air raids on the civilian population. To me, that is not a victory. On a strictly military basis, we would not have been defeated. Now, we have to bite into our sour apple and follow the orders of the Military Occupation.

“What are Vati and Manny doing? The cruiser Lützow was sunk by the English. We do not know whether or not Manny was still on it. This uncertainty is awful.”

Propaganda lies contrast a stark reality

Wolfhilde was a much better daughter and sister than a fair military analyst or open-eyed witness to the responsibilities of regime’s war policies.

To begin with, the bombings of largely-civilian cities were first ordered by the Fascist regimes of the Führer and Benito Mussolini during the Spanish Civil War. The infamous carpet bombing of the small Basque town of Guernica, its horror immortalized by one of Pablo Picasso’s most famous painting, was conducted by both German and Italian bombers on April 26, 1937.

This was followed by the razing of Warsaw, Poland, in 1939 by the Luftwaffe, then one year later by the ongoing Blitz on London and other British cities, also by the same Luftwaffe bombers. Substantial air bombing of German cities by Allied air forces didn’t start until well into 1942. Winston Churchill also never said the words Wolfhilde assigns to him.

Separately, the liberation of Munich on April 30, 1945, coincided with the liberation of Dachau, situated just a few miles north of Wolfhilde’s home. Part of the Holocaust was still being conducted there when the camp’s gates were forced open. Some 32,000 survivors were freed, some of whom died shortly after their liberation. The ovens were still warm. That mind-blinding horror was quickly and amply publicized in the local and international press.

How could Wolfhilde not even mention it? Deutschland über Alles syndrome? Here are two telling contemporary quotes from her war diary:

June 5, 1945: “Schwabing has become a hospital for foreigners. And I no longer go there. I really have no desire to nurse Jews or Ukrainian back to health. […] Everywhere one can see the hunger problem. The bread ration has been decreased to 700 grams. Most people do not have any more potatoes. All other rations are equally hard to come by. There is, however, still worse to come. The people will eventually see what it means to be a lost people, when the entire blame is placed on us.”

July 5, 1945: “We have arranged our living room in pleasant fashion. My bedroom faces the front. Our piano is being brought upstairs. Gradually life is becoming more comfortable again. Where can Vati and Manny be? One is always expectant and, therefore, time passes quickly.”

After the final National Socialist German Workers’ Party leaders surrendered, the German population was still at starvation level for a long time, worsened by the massive influx of German refugees expelled from liberated Eastern European countries. It’s a mystery how Wolfhilde and her mother recovered so quickly.

Some good luck for the von König family

Wolfhilde happily describes her father’s mid-summer return in her war diary, first hinted at on August 7, 1945, then realized five days later:

“Finally, some news from Vati. A woman brought us a small piece of paper with greetings from Vati, informing us that he will be home soon. A soldier from Westerland [Sylt] had brought the news. Now we have that to look forward to. We hope that he will be able to handle the stress. He is healthy and has felt good all along, so he can begin his voyage in good condition.”

Here, Wolfhide’s warm family-loving side is shining bright. It will prove a major instrument of her eventual redemption.

“Vati came home!! All the waiting has come to an end. He arrived early in the morning at 6:30 am. He looks great. Thank God he had been assigned to a good place. He travelled zigzag for 10 days through the whole German countryside, which lies there destroyed. The story telling has no end. Where can our Manny be? Our thoughts keep drifting back to him. Only God knows where he is.”

After that felicitous moment, Wolfhilde never revealed in her war diary the crucial financial decision her reunited parents made within two or three weeks. The question they faced was how to allocate their savings earmarked for their two children’s higher education.

The dilemma was that Wolfhilde, now 19, stood ready to start medical school to become a doctor. She’d spent the whole war with doctors in hospitals, learning how to care for and treat wounded soldiers and civilians. She’d become very good at it and enjoyed the work. That made her decide medicine was her calling.

Out of Soviet hands (almost)

Here is a good time to catch up with Emanuel von König in early July 1945, the day he was let free and nearly “good as dead” by his Soviet guards, thanks to the pivotal help of one of his father’s early war buddies. He wrote:

“A small group of us made our way to the railroad station and waited for a train going in the direction of Berlin. There we found shelter for the night. The next morning, we started walking to the station from which our next train would be leaving. People recognized us as released POWs and we were constantly approached and questioned if we knew anything about a loved one.

“On the continuation of my trip I had to transfer a few times and ultimately in the town of Eilenburg on the river Mulde near Leipzig. The train could go no further. The Russians had declared the river a demarcation line and one could only cross with a special pass.”

Here was one more of many early hints at Joseph Stalin’s intention not to respect the Yalta Agreement of early February 1945, that people from all the regions and countries of freed Europe would be allowed to have democratic control. It was one of many small hints, but they’d take time to be noticed in Washington, DC.

While now inside the territory of post-war Germany, von König was still, in effect, a Soviet prisoner; one more happy conspiracy between fate and Lady Luck. He had no choice but to deal with his reality, especially his deeply traumatized physiology, which was now close to breakdown. He wrote next:

“I ended up in a refugee camp and after a few days developed pleurisy. Twice a week the ambulance from the hospital, located on the other side of the river, was allowed to enter the camp and take the two worst cases with them. After about two weeks, I was taken.”

Incredibly, his near-death state had, once again, just granted him a new chance to survive and also brought him to a German town under lesser Soviet control. Crucially, for the first time since his capture back in April 1945, von König could enjoy the benefits of modern medicine. He recounted this transition after he was picked up by the ambulance crew:

“I must have been quite a sight, dirty and unwashed, down to about 130 pounds. Once in the hospital, I only remember being undressed and lowered into a tub with nice warm water, then I passed out. When I woke up, I found myself into a single bedroom. I took three procedures to remove all the blood from my lung cavity. After some weeks I was moved to a general ward where I had to teach my spindly legs to walk again.”

Wolfhilde von König describes her brother’s condition

In a year-end diary entry, Wolfhilde provided a professional description of her brother’s state in his first days at Eilenburg Hospital, based on letters from him. Here is her clear medical description:

“When he was admitted there on July 7, his head was bald and he only weighted 128 pounds. On his first day there, 200 cc of pleural fluid [not blood] was taken out of the space between his lungs and; on the fourth day, 800 cc. His left lung had completely collapsed, meaning that it barely functioned.”

Reminder: those 128 pounds were thinly distributed over a body height now closing on six-feet, two-inches.

On August 8, 1945, even before Emanuel von König could start to “teach his spindly legs to walk again,” he sat down to write a letter to his family at their Munich address, presuming correctly that they were there and safe. Knowing they were stressfully in the dark of his whereabouts, let alone whether he was even alive, this had been his first priority once able to put pen to paper.

If his letter, posted that day, had traveled to Munich, even at the speed of mail in early-1944 Germany, it might have been read by his parents when there was still a chance to influence their key financial decision. Alas, this was now post-war Germany, with mail connections between the Soviet zone and the American zone – of which Munich was part – deliberately slow. His “first sign of life” letter didn’t get to the family apartment until November 8.

Emanuel von König, the forgotten man?

The letter’s arrival merited only a casual report from Wolfhilde in her war diary on November 8, 1945:

“I am celebrating my 20th Birthday today. Yet I am not quite in the mood. We received the first news from Manny which was dated August 8, which means that it was written three months ago. Back then he was lying in the hospital in Eilenburg near Leipzig. He is in the Russian zone, but thank God as a civilian.

“The Russians have no use for sick people. Let us hope that he comes home soon; then he will get nursed back to health. He only weighs 120 pounds now, a second Gandhi. Hopefully, he will be able to cross the border. I wish he was already here.”

She goes on for a few lines describing a few of the birthday gifts she received that day, even admitting that one’s 20th is a date to celebrate for anyone. Her lack of excitement and overt joy, however, is quite noticeable. No “OMG, Manny is alive; this is the best birthday gift I would have hoped for!” Most likely, the allocation of the family’s savings to her pulled at her conscience.

Suffering from health setbacks

Meanwhile, Emanuel von König had been making his own uneven and slow progress in Eilenburg shortly after writing his first letter. He later wrote:

“As time passed, I regained my strength and put weight back on. After about five months, things became quite boring and I asked to be given something to do. I started helping out in the lab and in the office. I was also encouraged to go on brisk walks to strengthen my leg muscles and give my lungs a workout.”

During that period, von König wrote another letter to his family, which was received on the last day of 1945, as recorded in his sister’s war diary, this time with renewed sisterly warmth:

“Today, we finally received news from Manny. He is still lying in the hospital in Eilenburg and has had to go through a lot. […] He can do easy jobs and so he helps in the different wards, is friendly with everyone – with the sweets manufacturers, station girls from the country etc. He is counting on being released on February or March.

“In November, he suddenly came down with Typhus. Where it came from is a riddle for everyone. Fortunately, he has recovered from it. We hope from the bottom of out hearts that he will be well soon and that he can come back to us.”

Wolfhilde von König starts dreaming of a medical career

In fact, her brother had recovered so quickly and so well from that fever that he managed to write yet another letter to his family before year’s end, which reached them on January 22, 1946. A sign of how quickly the German mail system was recovering. This was duly noted in Wolfhilde’s war diary. She also revealed her progress with her career goals:

“For the time being, I am once again elated. I finally received my admission to the university, after having been first denied. Now I can get on with my medical studies I am simply happy.

“And today we received news from Manny. Judging by the of his letter, he is merry as a cricket. His health is improving and he is still receiving great nursing care. Thank God things are going so well for him. Others report horrible things from the Russian-occupied zone. We are happy that he is doing well and has found his sense of humor again.”

Emanuel von König suffers another relapse

Wolfhilde’s next war diary entry about her brother was on his birthday – March 16, 1946:

“Today is Manny’s birthday. He is 19 years old. He is slowly getting ready for his return home. If he were here already! The crossing of the border can be a tricky situation. Let us hope that everything goes well and that he reaches us in good health. Whatever his future may be, it will be determine then.”

Alas, once again, patience was the order for the times. A little over a month later, on their mother’s birthday, Wolfhilde wrote about her brother’s new plight on April 21:

“Easter – Mutti’s birthday. When I think back to last year, it all seems to have been a bad dream, what was then and what is now. […] Manny has still not come back. His doctor will not give him permission to travel. His blood sedimentation rate (ESR) is just too high: 65/110. He is only gradually improving It is better this way than if he were to collapse on his way back. He is being nursed back to hell and, at least, he does not lack for anything where he is.

“Hopefully, he will come in May or June.”

Emanuel von König finally makes it home

We now return, again, to Emanuel von König’s recollections of his highly emotional walk to his family’s apartment:

“After a total time of 11 months, I finally was able to continue my journey and arrived in Munich in mid-June of 1946. I walked home from the railroad station. It felt so good to see the city again. On the way, I met an old school friend. He greeted me and I started crying. My nerves let go.

“After I collected myself I continued and when I turned the corner into our street, I saw my father leaning out the window, smoking. I was halfway down the street before he recognized me and let out a holler. My parents and my sister were delighted to see me again. Happy reunion!

Wolfhilde recounts her brother’s return in a war diary entry, dated June 6, 1946. Strangely, or in an unconsciously revealing way, she turns to the subject of her “lost brother’s” return factually, with no expressed emotion and a rather patronizing tone, and this only after a long recitation of the hard manual work she was forced to do as part of her official political reprogramming duties:

“Manny’s long awaited homecoming finally took place after I got home yesterday. Now there will be long hours of story-telling. He looks well, has recovered remarkably. Now he will be returning to school again so that he can earn a high school diploma, a goal which will yet cost him some sweat. But he is here, in his home, and that is the most important thing.“

Freedom comes with some serious disillusions

Emanuel von König reported his prosaic new situation, as follows in his 2005 recollections:

“After a few days I reported to the Veteran’s administration. Based on the test made it was determined that I had a somewhat reduced lung capacity and what would today be described as Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. I was temporarily classified [50 percent] disabled. I received an additional allotment of food coupons and within a short time, I was also sent to a rehabilitation facility in Ambach on Lake Starnberg. I stayed there for four weeks.”

He then touched upon the delicate subject of his parents’ decision, writing:

“Lacking any other information, my parents had to assume that I went down with the ship. Based on this assumption, they decided to apply all available funds towards enabling my sister to continue her studies and become a doctor.”

He further elaborated:

“When I returned, my parents told me about their decision regarding my sister’s education. I understood their reasoning. Although I did not agree with what seemed to be an unfair agreement – that they would continue her schooling tuition but could not afford to pay mine as well, I had to accept it.”

That tough parental decision, while he could understand it rationally, did leave a bitter sense of injustice in his emotional mind for a very long time.

Confronting a new reality with spirited courage

All this was followed by Emanuel von König’s first consideration about the great catching-up job he’d have to undertake to make up for his numerous missed educational year. He wrote:

“Mid-August arrived and it was time to think about going back to high school. Nineteen years old already, with still my junior and senior year before I could graduate.”

It didn’t take him long to embark on this huge educational task, as he explained:

“I returned to the Luitpold Real Schule in September, 1946. By the time I graduated on July 14, 1948 from an eight year course at this school, I had completed eight (albeit interrupted) years of German, History, Mathematics, Geography, Physical Education and Arts.; six years of Physics, Latin and Biology; and four years of English, Music, and Chemistry. I was 21 years old.”

This is, of course, quite impressive, although the the range of topics was typical of German/West European post-war educational systems. Surely, the renown Luitpold Real Schule level of teaching was very high. While von König next needed to get into the University of Munich as soon as he could, the family savings had been assigned to his sister when he was thought to have died in the Royal Air Force raid, meaning he would have to get by on his own.

Germany was split into different zones in the post-war era

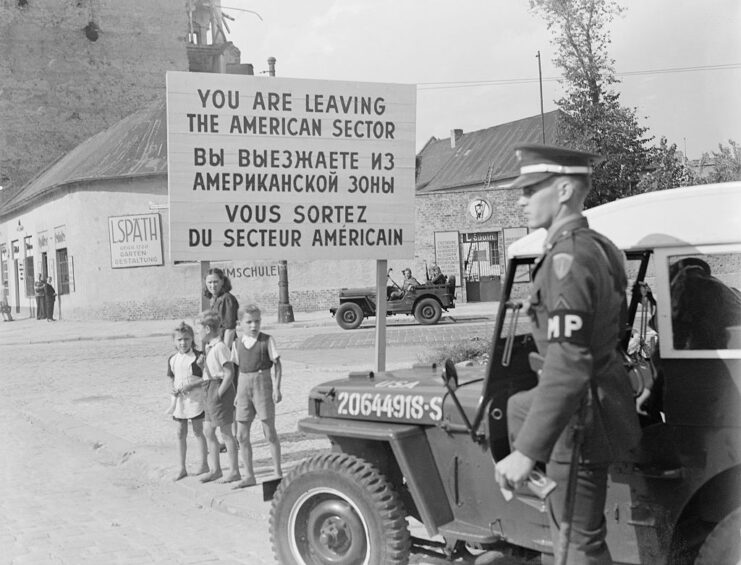

All of Bavaria, including Munich, was part of the American Occupation Zone, one of four zones decided at Yalta in February 1945. France had its own zone in the west, along its border with Germany; the British held the north-center; the Americans controlled the south-center; and the Soviets had all of the northeast.

The American Zone was surely the best to be in. Firstly, the United States had become the dominant superpower as World War II took its course, so the key policies in occupied Germany outside of the Soviet Zone were decided in Washington. Second, after an early hesitation about cooperating with Joseph Stalin, President Harry Truman soon realized he and his government were better off rebuilding Germany as a democracy, to counter the increasing sovietization of Eastern European countries.

Lastly, for a long time after the war’s end, Germany’s economy was a disaster; food was extremely scarce, housing was very tight, due to the destruction wrought by Allied bombings, and there was an influx of at least 12 million German refugees from the lost eastern states (East Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia). Bartering reigned supreme. The old Reichsmark had mere token value, while tobacco in all its forms actually became the new de facto currency – and Americans, of course, had the best cigarettes!

Making money and skippering on the Big Lake

Emanuel von König made himself money in two ways. While in high school, he’d become an adept agent in the black market for American tobacco. While he didn’t make a fortune, it helped him live a bit more comfortably than many of his peers. It also made him friends among US Army personnel.

Since his quasi-military training in the late 1930s had included sailing on the vast and spectacular Lake Starnberg, southwest of Munich, that suggested to him another opportunity. Hearing from his American officer friends that they’d love to take recreational boat rides during their days off, he asked them to help him join the Yacht Club in the summer of 1948. He could then be their highly-knowledgeable skipper and tourist guide.

Soon, von König’s US Army friends and their buddies were boarding his ship by the dozens. By November of the following year, he’d saved enough money to afford attending the University of Munich, but his American friends had more ambitious plans for the skipper.

Seeing he was a highly intelligent and talented young man who could help build a new democratic Germany, they encouraged him to apply for a Fulbright Scholarship, a new prestigious program designed just for the purpose of spreading democratic ideals among foreign citizens. It consisted of of full year at an American university of one’s choice, all expenses paid. It just so happened that, by July 1950, von König had passed the test and was awarded the scholarship by the US State Department.

He was due to depart for New York that August on the large passenger ship, SS Brazil.

Turning ‘Full American’

From New York, Emanuel von König would take the train to Minnesota, as that was where he’d been assigned after he answered “one in the middle of the country” when asked what university he wished to join; a revelation of how little he knew about the US university system, a realm he most likely had never dreamed of joining.

More from us: EXCERPT: ‘Witty Manny’ – How a Man Drilled in Tyranny Became a Thriving Citizen of American Democracy

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

How von König went on to marry a smart and lovely American woman, have four sons with her, become a proud American citizen and serve in the US Army Reserve, all while managing a successful career with the Whirlpool Corporation that saw him retire as the company’s international vice president, is forthcoming in our full biography.

Philippe Defechereux earned a Masters Degree in Business from Manhattan’s Columbia University in 1972. Over the next 25 years, he became a successful New York and Detroit advertising executive, a published author in both English and French, a History buff and a car racing fan.

In the mid-1990s, he decided to try his hand at authoring his first book. He opted to focus on the history of car racing. His first opus would be devoted to the birth of European road racing in America after World War II. That first book came out in 1998.

It quickly sold out its run and generated acclaim from racing clubs and veterans. So strong was its halo that it got the attention of automotive publisher Dalton Watson Fine Books. In 2011, a much enhanced and expanded second edition came out, retitled, Watkins Glen 1948-1952 – Glory, Drama and the Birth of American Road Racing.