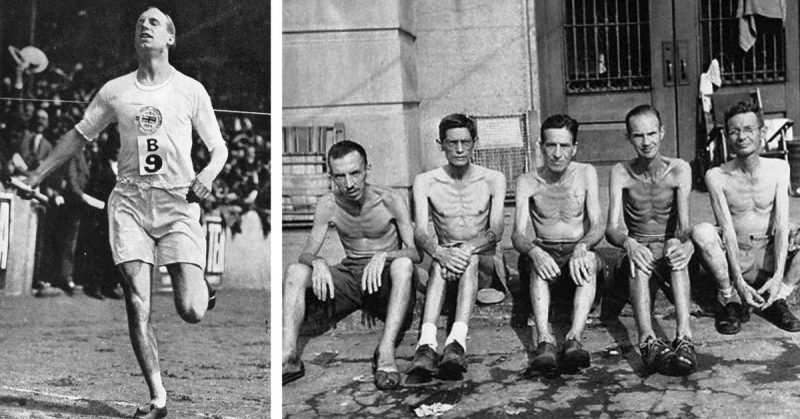

The Scotsman Eric Liddell is best remembered for his sporting accomplishments from the 1981 film that dramatized them, Chariots of Fire.

However, his record-breaking performance in the 1924 Olympics was not his only achievement. Locked up in a Japanese internment camp during the Second World War, Liddell once again showed his incredible strength of character.

A Missionary Childhood

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, missionary work played an important part in Britain’s relationship with the rest of the world. Dedicated Christians traveled enormous distances with the limited technology of the time to live and preach in distant countries.

Eric Liddell’s father was such a missionary, and his mother who was a nurse joined in his work. Eric was born in 1902 in the busy Chinese town of Tientsin. On reaching school age, he was sent back to Britain to attend boarding school.

Sporting Career

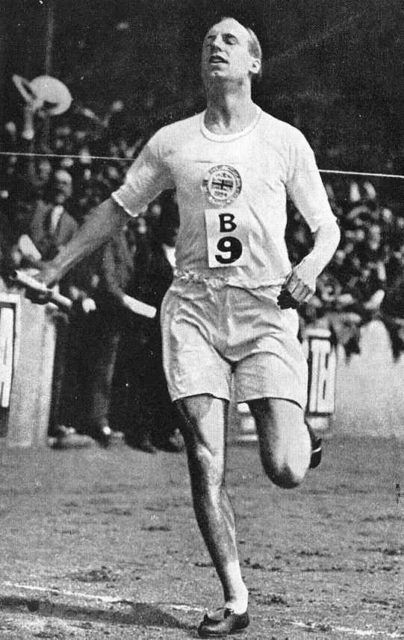

As a boy, Liddell showed a gift for sports, especially running. He was an outstanding athlete during his time at Edinburgh University from 1920 to 1924.

While at university, Liddell played for the Scottish national rugby team, scoring tries against France, Ireland, and Wales. However, he excelled as a short distance runner.

At the 1924 Summer Olympics, he refused to take part in the 100 meters race as it involved running on a Sunday, which went against his strict religious values. Instead, he ran in the 400 meters, won and set a new world record.

Back to China

Liddell was an incredible athlete, but his passion was religion. After university, he trained as a missionary then returned to China in 1925. In Tientsin, he taught chemistry to Chinese and European students at the Anglo-Chinese College. He also led Bible studies and coached team sports and athletics. When his father retired in 1929, he became superintendent of their church.

Liddell met Florence MacKenzie, the daughter of Canadian missionaries. They were married in 1934 and had three daughters. However, the turmoil coming to China meant Liddell never met his third child.

War Comes to China

The Asian front of the Second World War opened two years before violence broke out in Europe.

In 1937, simmering tensions between China and Japan turned into open war. For the next eight years, the Japanese fought the separate armies of the Communist and Nationalist Chinese, already at war with each other. Law and order collapsed in Northern China.

The countryside around Tientsin became a dangerous place. Chinese Christian communities faced great hazards. It was hard to find missionaries to serve in them.

Siaochang

The London Missionary Society asked Liddell to take up a placement at the Siaochang mission. Serving rural communities scattered across swathes of countryside, this would have been a challenging post at the best of times.

These were not the best of times.

After careful thought, prayer, and discussion with Florence, Liddell decided to take the position. Leaving his wife and two daughters behind, he headed north.

He excelled in his new role. Traveling from village to village by bicycle, he supported local preachers and made converts among the population. Meanwhile, war raged around them.

From 1939 to 1940, Liddell took a break in Scotland with his family. Then they traveled to Canada in a convoy that came under attack from German submarines.

Finally returning to Tientsin in 1941, they learned that Siaochang mission station had been destroyed. The war had touched directly on their home. Florence and the girls headed back to the safety of Canada, while Liddell remained to continue his work.

Into Internment

In December 1941, Britain and Japan went to war. The Japanese had occupied Tientsin and Liddell was now an enemy alien. Harsh restrictions were placed on foreigners working in the region. Meetings of more than ten people were banned. Missionary work was almost impossible.

In March 1943, all foreigners in Tientsin were told to prepare for internment. Liddell and his peers were forced to march through town with the limited belongings they could take with them, put on trains, and transported away.

Weihsien Internment Camp

Liddell’s place of imprisonment was particularly appropriate. Weihsien internment camp had been a missionary base, its formerly peaceful walls now guarded by barbed wire and sentries.

Conditions in Weihsien were harsh. Food supplies were limited. The people already there when Liddell arrived were emaciated. Strict rules and twice-a-day roll-calls kept the prisoners in order.

Within the camp, the detainees time was largely their own. They organized themselves, creating a school, entertainment, religious meetings, and even something like a hospital.

Freedom had been taken but life went on.

Preacher and Leader

Liddell was made warden for two of the accommodation blocks, responsible for taking their roll-calls.

His leadership went beyond his official position. He was constantly looking out for his fellow prisoners, providing care and support. He arranged sports events, taught science using a home-made textbook, carried supplies to the old and sick, and ran a Sunday School for the children.

In this way, he continued his missionary work in the harshest of conditions. Guided by his religious principles, he preached the word of God and provided counseling to those he saw as in his care.

Strong to the End

He continued for nearly two years, keeping alive the hopes of those around him. Then, in early 1945, he became sick with a brain tumor. It developed quickly. There was nothing that could be done given the facilities of the camp.

He remained strong and inspiring to the end, requesting songs from the band who played outside his infirmary window. Following his death on February 21, the whole camp turned out for his funeral.

He had helped them to survive terrible hardships. In the face of war and deprivation, Eric Liddell remained strong.

Source:

Gordon Brown (2008), Wartime Courage.