The grandson of slaves, he got a college degree and became an international legend. Despite being sickly, he set athletic records that took decades to break. And though he was black, he befriended a Nazi.

That man was James “Jesse” Cleveland Owens. Born in Oakville, Alabama on September 12, 1913, poverty, lack of adequate housing, clothing, and food meant he was a sickly child who suffered from bouts of pneumonia. Despite this, he was expected to pick 100 pounds of cotton by the time he was seven.

Little wonder, then, that he suffered from chronic bronchial congestion. By the time he was nine, his family couldn’t take it anymore, so they joined 1.5 million other African-Americans in the Great Migration out of the South.

In Cleveland, Ohio, Owens’ new teacher asked him what his name was. He replied, “JC,” in a thick, Southern accent, which she misheard as “Jesse.” The name stuck.

It was at the Fairmount Junior High School, under coach Charles Riley, that Owens discovered his passion for running. And because he worked at a shoe repair shop after school, Riley let him train in the morning before classes.

It all paid off in 1933 at the East Technical High School, also in Cleveland. Owens joined the National High School Championship in Chicago and ran 9.4 seconds in the 100-yard dash, as well as jumped 24’ 9½” in the long jump – equaling the world record. The entire country noticed.

But it changed nothing. Owens went to The Ohio State University by working to pay his way since blacks weren’t eligible for scholarships. Nor could they live on campus.

He got his revenge by winning eight NCAA Championships in 1935 and 1936. They called him the “Buckeye Bullet” after that. Still, he couldn’t eat or stay with the other white athletes. For him, there was either take-out or black-only restaurants while staying at black-only motels.

Not that it stopped Owens. His results qualified him for the Big Ten meet at Ferry Field in Ann Arbor where he became a legend. He almost missed it, though. Two weeks before the event, he slipped and badly injured his tailbone.

On May 25, 1935, he couldn’t even bend down to touch his knees. But that didn’t stop him, either. Owens set three world records for: (1) the long jump at 26’ 8¼” – which wouldn’t be broken for 25 years, (2) the 220-yard sprint in 20.3 seconds, and (3) the 220-yard low hurdles at 22.6 seconds. Oh, how everyone’s jaws dropped.

Perhaps exhausted, Owens settled for equaling the record for the 100-yard dash in 9.4 seconds. When asked about his injury, he claimed that the pain “miraculously disappeared.”

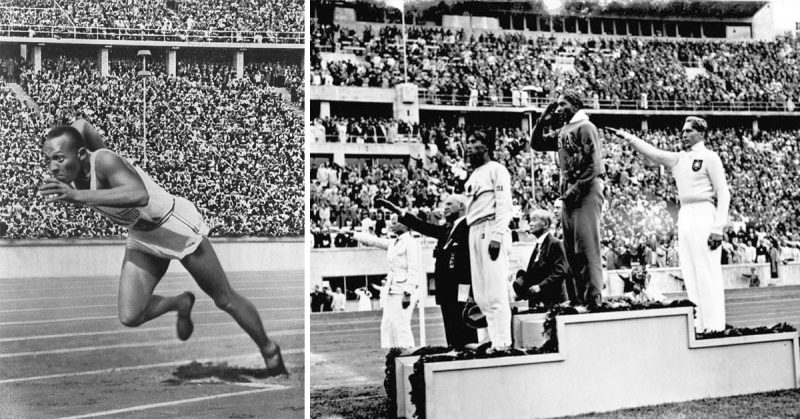

So now the whole world knew about Jesse Owens – qualifying him for the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Which annoyed Hitler, of course.

Besides showing off Germany’s new might, the games were supposed to prove the supremacy of the Aryan race. German papers ridiculed the US for sending in “black auxiliaries” and for allowing “non-humans” to compete.

As for the rest of Germany, they only knew the name “Jesse Owens,” not what he looked like. So when he arrived in Berlin, fans kept asking “where is Jessie?” – not realizing he was the black guy standing in front of them.

When they found out he was black, it got worse. Women waved scissors, wanting a piece of his hair and clothes as souvenirs. Others wanted his picture and autograph – further infuriating German officials. To protect him from his fans, he needed a police escort.

Despite this, and to the surprise of the African-Americans, they were kept in the same Olympic Village as the other whites and ate in the same restaurants. And to Owens’ even greater surprise, 110,000 fans cheered as he walked into the Olympic Stadium.

On August 3, he won his first final by running the 100-meter dash in 10.3 seconds – edging out Ralph Metcalf (another African-American). But his luck turned the next day.

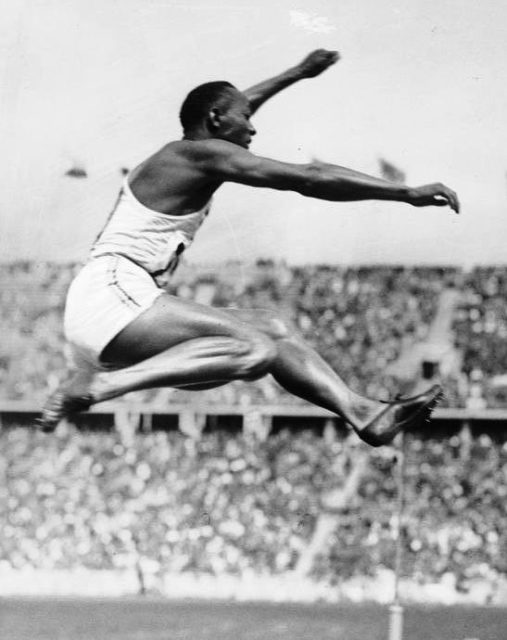

To qualify for the long jump, he was allowed three trial runs. Feeling confident, Owens did a warm-up run. But as he got ready for his first trial, the officials shook their heads. The warm-up counted, leaving him two more tries. So he did his second… and failed.

One more left. The pressure finally broke him. Owens deflated, squatting on the field with bowed head.

Enter Carl Ludwig “Luz” Long. Blond-haired, blue-eyed, and a little more than six feet tall – he was the perfect Aryan. He had also won the German long jump championships three times and held the European record for the event.

“Step back several inches before the take-off board,” the golden one said.

Owens stared at him blankly.

“Make a mark several inches behind the board and jump from there. It’ll give you more leverage without violating the rules.”

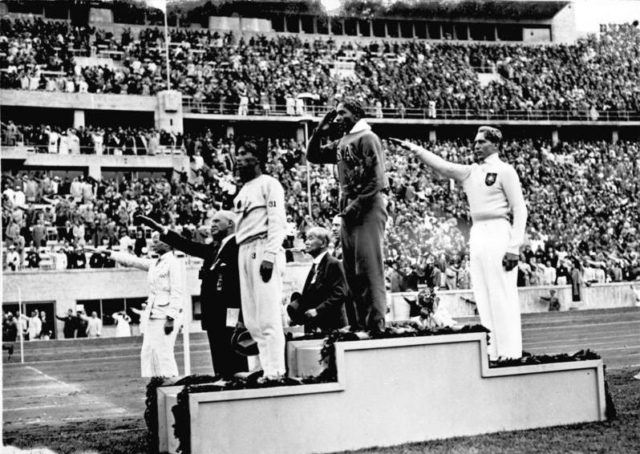

Owens did so… and made it! Later that afternoon, the two went head-to-head. Owens won the long jump at 26’ 5”, beating Long, who ran out to embrace him.

Owens later claimed that, “It took a lot of courage for him to befriend me in front of Hitler… You can melt down all the medals and cups I have and they wouldn’t be a plating on the 24-karat friendship I felt for Luz Long at that moment. Hitler must have gone crazy watching us embrace.”

It was brave. According to Long’s mother, Rudolf Hess (Hitler’s deputy minister), later ordered Luz to “never embrace a negro again.”

Two days later, Owens defeated Mack Robinson by running the 200-meter sprint in 20.7 seconds. His fourth gold came on August 9 after running the 4×100-meter sprint in 39.8 seconds – setting yet another record.

Owens and Long stayed in touch, even when the latter joined the Wehrmacht. Long wrote his last letter to Owens in 1942, asking the American to visit his son after the war and to let the boy know “how things can be between men on this earth.” He signed it by calling Owens his brother before dying in action on July 14, 1943.

In 1951, Owens returned to Berlin and met Long’s surviving son – the ten-year-old Kai-Heinrich. The two stayed in touch, and Owens later became the best man at Kai’s wedding.

Owens’ death on March 31, 1980 didn’t mean the end, however. In 2009, Marlene Owens Dortch (his granddaughter) and Kai attended the 12th IAAF World Championships in Athletics in Berlin at the Olympic Stadium where Long and Owens first met. And they were placed in the very box that Hitler and his lackeys had sat in, all those years ago.

Now how’s that for irony?

Long Jump Video

Original footage of the long jump at the 1936 Olympics