One of Nazi Germany’s greatest military planners, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein displayed a thorough understanding of the use of strategy. However, his conclusions were not always what Hitler wanted to hear.

An Army Child

Erich was born into the Lewinski family in Berlin on November 24, 1887. Childless relatives on his mother’s side adopted him, and he was given their surname.

Both families were descended from Prussia’s military nobility. As an army child, Manstein moved around to where his father was stationed. After an education at Strasbourg, he attended military cadet training at Ploen and Berlin.

During WWI, he served on the Russian front. After being injured while charging a Russian position, he became a staff officer, fighting on both fronts.

The Military Planner

Given his skill and experience, Manstein remained in the army when it was dramatically reduced after the war. Germany was not allowed a general staff, but effectively had one disguised under a bland name. Manstein was part of that group. He developed mobilization plans, crafted war games, and assessed proposals to bring in new weapons and tactics.

By 1939, he was a general with experience on the staff of several senior commanders.

Victory in the West

Before the outbreak of WWII, Manstein was on the staff preparing for the invasion of Poland. Following that campaign, he was moved west to take part in planning for the invasion of France.

Manstein was disappointed by what he found. At the highest level, Hitler and those around him had no strategic plan for the war. The question of whether to seek a political settlement or fight until the enemy was forced to make peace had not been considered.

He disagreed with the strategy for invading France. He believed a single strong strike would work better than what the generals had planned. To stop him interfering, he was transferred to a field command. Then he was summoned to brief Hitler on the plans and won the Fuhrer round with his bold strategy. Manstein’s scheme was adopted and led to the swift fall of France.

The Crimea

After the victory in the west, Manstein traveled east again. There he took part in the invasion of Russia.

Following early successes, he was given command of the army fighting for the Crimea. There, he encountered the same problem the British and French had during the Crimean War – the city of Sevastopol.

Sevastopol’s defenses held off the Germans for months. Instead of focusing on the city, Manstein fought around it. Once the surrounding Russian forces had been defeated he brought massive siege guns into place to attack the city.

Sevastopol finally fell.

The Stalingrad Problem

For his success at Sevastopol in the summer of 1942, Manstein was promoted to field marshal. It was little consolation for the loss of his son, who had died earlier that year.

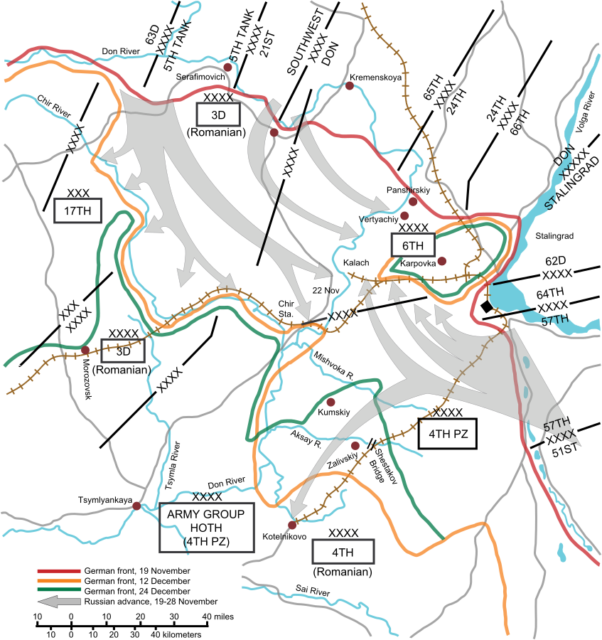

Manstein joined the action around Stalingrad. There, the German offensive had stalled. German troops were under growing pressure from Russian forces and a lack of supplies.

Manstein saw that the surrounded German army was doomed. He repeatedly asked Hitler to let them retreat, regroup, and launch a new offensive. Hitler would not allow it. Manstein, a loyal soldier, would not contradict the Fuhrer’s orders and refused to give the order to break out.

Stopping the Winter Offensive

When the Soviets launched a fresh offensive at Christmas 1942, Manstein again found his views at odds with Hitler’s. Hitler, with little grasp of strategy, wanted the Germans to cling to every inch of ground. Manstein wanted a war of movement and maneuver.

After much debate, Hitler grudgingly let Manstein fight his own way. The Russian winter offensive was halted in March using Manstein’s tactics. However, it left the Russians holding a salient deep into the German lines.

Citadel

Hitler ordered Operation Citadel which was an offensive to cut off the Soviets in the Kursk salient. Manstein led one of the two parts of the pincer movement.

Operation Citadel made progress, but it did so slowly. The impatient Hitler decided to divert forces to deal with the Allied invasion of Sicily. To do so, he called off the operation, just as the frustrated Manstein believed he was on the verge of victory.

Withdrawal

The emboldened Russians launched fresh offensives. Seeing they could not hold their position, Manstein turned all his logistical and strategic skill towards a withdrawal across the Dnieper. With only a few river crossings and the enormous quantity of troops making the task extremely difficult, he pulled it off with finesse.

The Final Falling Out

In the early months of 1944, Manstein repeatedly begged Hitler for more freedom to fight the war his way. Manstein believed that, with a war of movement and maneuver, he could hold back the Soviets. Hitler disagreed.

As Manstein’s temper frayed, he made critical errors by interrupting the Fuhrer and making sarcastic comments about his plans. On March 25, Hitler tried to shift the blame for Germany’s failure onto Manstein, who responded in kind.

Finally, on March 30, events came to a head. Hitler awarded Manstein the Swords to the Oak Leaf of the Knight’s Cross, then relieved him of duty. Given the bitterness between them, it could have been far worse for the field marshal.

After the War

Manstein sat out the rest of WWII. Following the war, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison for war crimes but was released early due to ill health.

In 1956, Manstein was called on by the West German government. They were setting up a new army, which would ally with their former opponents to face the threat of Russia. Few men knew how to fight the Russians better than Manstein.

He spent his last years in Bavaria with his family and died on June 10, 1973.

Source:

James Lucas (1996), Hitler’s Enforcers: Leaders of the German War Machine 1939-1945