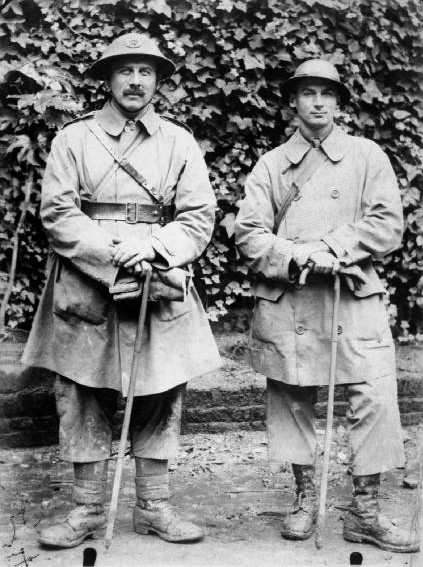

Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, widely known as Monty, was the foremost British commander of the Second World War. Popular with his troops, he was less liked by politicians and allies, due to his outspoken approach. Despite these difficulties, he made a huge contribution to the Allied war effort.

An Eccentric Start

Bernard Law Montgomery was born in 1887. Educated at St Paul’s School, he went on from there to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst.

Montgomery was not among the leading lights of his class. Demoted for setting fire to a fellow cadet, he managed to graduate, but not high enough in his class to take a coveted post in the British Indian army. Instead, he was commissioned into the Royal Warwick Regiment.

The First World War

Throughout World War One, Montgomery served as an infantry officer. He was severely wounded at the First Battle of Ypres, progressed up to the position of divisional chief of staff, and by the time the war ended he was a lieutenant-colonel.

The Great War had a huge impact on Montgomery, shaping his opinions in two key ways. Firstly, the devastating losses of battles such as the Somme made him determined never to use the senseless tactics that turned men into cannon fodder, an approach he referred to as “mismanaged butchery”. Secondly, he came to the conclusion that military command required the serious commitment of life-long study. He would take his work, and his study of his profession, incredibly seriously.

Between the Wars

During the inter-war years, Montgomery watched the British army suffer from neglect. He believed that the troops were poorly equipped, poorly trained and poorly led. The army, in his view, lacked the doctrines necessary to fight a modern war.

His wife’s early death led him to commit himself ever more firmly to his professional life. Despite his vocal dissent in a nation and profession more comfortable with calm conformity, by 1939 Montgomery had reached the rank of major-general.

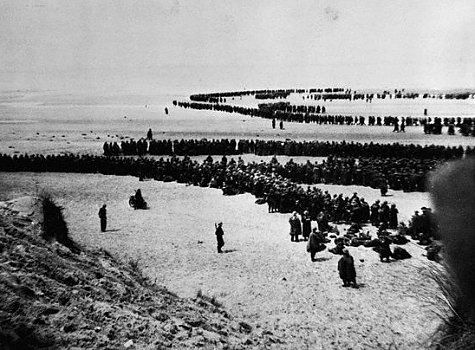

Dunkirk

The early days of Second World War would vindicate Montgomery, both in his views on the state of the army and in the disciplined effort he had put into training the men under him. The 3rd Division, which he commanded, was in the vanguard of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France, where they proved their competence. Though he fought brilliantly, Montgomery was caught up within a wider disaster, as France fell and the BEF retreated. He was one of the last senior officers out of Dunkirk.

Having been proven correct, Montgomery was given increasingly senior positions commanding Britain’s defences. He may have been undiplomatic in nature, but he had been proven right and in a time of war that was far more important.

North Africa

In August 1942, Montgomery was made commander of British forces in North Africa. There he turned the dispirited 8th Army into the greatest British fighting force of the war, in large part by selecting the best officers to command and then leaving them free to do their jobs. He defeated Rommel at Alam Halfa and El Alamein, becoming a national hero, but was criticised for not doing more to pursue retreating Axis forces.

As Americans joined the British in North Africa, Montgomery became part of the problem of Anglo-American relations. The British saw the Americans as incompetent, the Americans saw the British as rude, and it was only through General Eisenhower’s careful handling that they worked so well together.

Knighted and promoted to full general, Montgomery led the British through the rest of the North Africa campaign and then in the invasion of Italy.

Overlord

At the end of 1943, Montgomery was withdrawn from Italy to take command of the 21st Army Group as it prepared for the long-planned invasion of occupied France. He was made Commander-in-Chief of the Allied forces for Operation Overlord, with the intention that he would hand command over to Eisenhower once a foothold was established on the continent.

Montgomery revised the plans for Overlord and led the Allies to success in the D-Day landings of June 1944. But the British stalled in their efforts to take the strategically important city of Caen, provoking further criticism of Montgomery as a commander. Despite this, he was promoted to Field Marshal in September.

Towards Berlin

Over the course of nearly a year, the Allies fought their way through France, the Low Countries, and Germany. As commander of the British forces, Montgomery continued to create a mixture of success and controversy. He and his men fought well, but Operation Market Garden, his attempt to form a bridgehead across the Rhine, was a costly disaster.

As the Allies pushed into Germany, Montgomery became a central and contentious figure in the debate on how to advance towards Berlin. While others argued for a general advance, he wanted to focus effort in a narrow front along a northern corridor, in the area where he commanded. While Montgomery’s plan had strategic advantages, political considerations meant that it could not be adopted.

The ire Montgomery provoked among other commanders meant that Eisenhower considered removing Montgomery from command. However, by this point he was to many an international hero, popular among his men and an excellent leader. He therefore retained his position, led a large Anglo-American force through the last months of the war, and accepted the surrender of German forces at Lüneberg in May 1945.

After the War

Montgomery’s light never again shone as brightly as it had in North Africa, but he remained a leading figure in the British military, serving as Chief of the Imperial General Staff and as Deputy Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. He was the most celebrated British commander of the 20th century, and when he died in 1976 a nation mourned.