Enlisting in the army is far from an easy decision, especially if your country is at war. The choice can be truly life-changing, and those who do enlist could find themselves facing deadly and dangerous situations. However, the soldiers who serve their country know that their selfless journey is about the bigger picture; promoting peace, freedom and stability for your nation and for the world at large.

Some who enlist in the armed forces do so without knowing exactly what’s in store for them, but they are willing to shoulder the burdens of whatever battlefield awaits them nonetheless. Many are willing to go the extra mile – to make extraordinary sacrifices, willingly risking their own lives for the greater good.

One soldier who fits that description is Arthur Louis Aaron, an Englishman who made that tremendously difficult choice and elected to dedicate himself to his country’s safety.

Aaron’s Life Before the War

Born in March 1922, Aaron grew up in Leeds, Yorkshire. He spent his earliest years at the Roundhay School before heading to college at the Leeds School of Architecture. It was during his time there that WWII broke out and, without hesitation, Aaron enlisted.

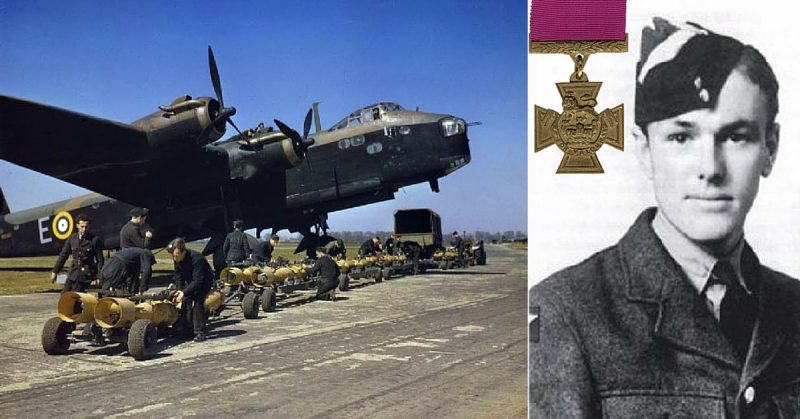

Once he had joined the military, Aaron became a member of the Royal Air Force. He went through training in Texas, before leaving the US and returning home to England. Once he made it back, Aaron joined the No. 218 “Gold Coast” Squadron, where he was trained and certified to fly the Short Stirling bomber planes.

The Beginning of the End

Sadly, Arthur Aaron was only 21 years old when his life was ended. At the time of his death, he had already logged roughly 90 hours of flight time, and carried out 19 sorties.

Now a Flight Sergeant, Aaron was flying a Stirling plane on August 12th, 1943, on his 20th sortie mission with his crew. As Captain and pilot of the Stirling, he had been given orders to attack Turin, in Italy. As he was approaching his target, his bomber was hit by machine-gun fire from an enemy fighter plane. Three of his engines were hit and severely damaged, and the plane’s windshield shattered. The turrets on both ends were shot, and even the elevator control was refusing to work properly. Due to all of these problems, the aircraft was completely unstable and nearly impossible to maneuver.

Yet that wasn’t even the worst of the attack. The Canadian navigator flying at Aaron’s side, Cornelius A. Brennan, had been hit by the gunfire and killed. Other members of the crew had also been wounded, including Aaron himself.

Aaron was forced to confront his own injuries, acknowledging that he had taken a bullet directly to the face. The aftermath was a broken jaw and part of his face being partially torn away. One of his lungs had also been damaged, and his right arm was nearly useless.

Reeling from his injuries, Aaron found himself almost unable to control his own body. He fell forward onto the control column, sending the aircraft into a rapid downward spiral. The Stirling dove several thousand feet before a flight engineer managed to move Aaron aside and regain control. He only managed to level the plane at 3,000 feet.

Having lost his ability to speak, Aaron could only use rough hand gestures to communicate with the bomb aimer. Once the latter was able to follow Aaron’s signals, they were able to work together to keep the highly-damaged plane flying one engine until they could reach Sicily or North Africa.

Once they were on the move, Flight Sergeant Aaron was treated with morphine, easing his pain and allowing him to focus on the task at hand. Remembering his place as Captain, he refused to sit back and do nothing. He guided himself with help from the crew back into the cockpit, where he was determined to take charge again.

Of course, he was too weak, and after arguing with the crew over his clearly debilitated state, Aaron backed down, allowing the others to successfully bring them to their destination. Despite his pain and exhaustion, he continued to relay information to them by writing instructions on his left hand.

Five hours had passed, and the fuel was running low. But soon Bone Airfield was in sight, near Annaba in Algeria. Aaron revived himself again to help the bomb aimer land the aircraft in the dark. With the undercarriage retracted from the initial blast, it took them five grueling attempts to bring the plane to rest. With Aaron’s health failing and the plane severely damaged, they finally landed safely.

However, even now, Flight Sergeant Aaron’s fate had already been decided. Nine hours after the landing, Aaron had died from his wounds, his body exhausted from the long struggle of the flight.

Perhaps if he had been able to conserve his strength he could have recovered. Yet Aaron’s determination to serve his country and save his crew from potentially falling into enemy territory wouldn’t allow him to give up, and he forced his ailing body to the point of no return. Thus, following his death, he received the Victoria Cross. The medal honored the courage, willpower and leadership he displayed throughout his short life, even in the face of death itself.

Remembering Flight Sergeant Arthur Louis Aaron

Aside from receiving the Victoria Cross, which is today displayed at the Leeds City Museum, Aaron also has a plaque in the main hall of the Roundhay School honoring his memory. He is also hailed as a hero in the AJEX Jewish Military Museum in London, as one of a small number of Jewish Victory Cross recipients from WWII.

Furthermore, as a sign to mark the new Millennium, the Leeds Civic Trust allowed the public to vote for a new statue to remember the city’s heroes – and Arthur Louis Aaron selected. A bronze sculpture was erected in his honor at one of the city’s busiest roundabouts near the West Yorkshire Playhouse.

Aaron’s figure can be seen standing next to a tree, on which three children are climbing; a representation of the passage of time between the years 1950 and 2000. The little girl at the top is shown releasing a dove of peace, signifying the ideals for which Aaron’s fought.

Perhaps the most poignant aspect of the statue was the man who unveiled it. His name was Malcolm Mitchem, and he was the last living survivor of the aircraft. Who better to honor the pilot than a crew member who lived on because of Aaron’s heroic sacrifice?