During the Second World War, a group of paratroopers earned a reputation for their unconventional behavior and combat tactics. Known as the ‘Filthy Thirteen,’ they were infamous for their disregard for military discipline and their rough appearance. Despite their unorthodox approach, they played a key role in several important missions, including D-Day.

Their story later became the subject of a well-known Hollywood movie – The Dirty Dozen (1967).

Who were the Filthy Thirteen?

Among the American airborne troops of World War II were the 1st Demolition Section, Regimental Headquarters Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. This 13-man unit was put together to serve as demolition experts, sabotaging targets deep behind enemy lines.

They were supposedly nicknamed the “Filthy Thirteen” while stationed in England, prior to moving into mainland Europe. The unit lived in barracks at the time and refused to bathe more than once a week. Why, you ask? They’d been poaching game from a nearby manor – an act for which the US Army would be charged $10,000 – and wanted to save their water rations to cook their prey. Even when they did clean themselves, they never washed their uniforms.

This was only the beginning. The Filthy Thirteen’s reputation as troublemakers quickly grew the longer they were overseas.

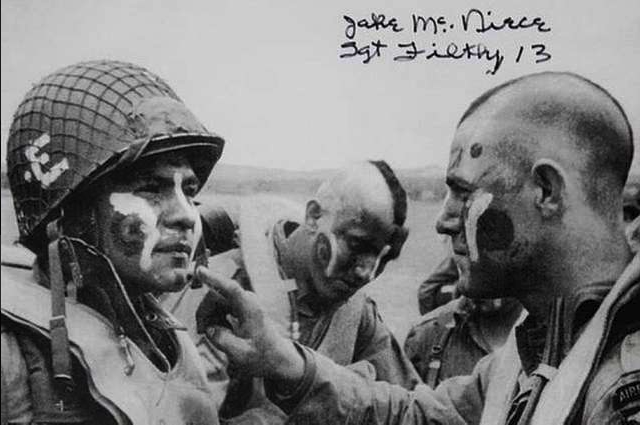

Sgt. Jake ‘McNasty’ McNiece

Undoubtedly one of the most famous members of the Filthy Thirteen was their fearless leader, Sgt. Jake “McNasty” McNiece. He wasn’t the first to lead them, however – that honor went to Lt. Charles Mellen, who was killed in action on D-Day.

McNiece was the main reason the unit became so famous in the first place. He thought that, by cutting their hair into mohawks and putting on warpaint, he’d help his men get ready for the difficult jump ahead of them. The idea was allegedly inspired by his Choctaw ancestry. According to his son, he thought, “If they’re scared of us as crazy paratroopers, well, this just makes us look crazier.”

Instead of anything fancy, the Filthy Thirteen used the still-drying paint from their aircraft’s invasion stripes. Photos of them doing this were published to great excitement back in the United States.

The Filthy Thirteen were larger than life

The Filthy Thirteen’s newfound fame only helped contribute to their status as legendary figures, and rumors – some true, some false – began to fly. McNiece confirmed some of them later in life, saying:

“We never took care of our barracks or any other thing, or sanitation, and we were always restricted to camp. But we went AWOL every weekend that we wanted to and we stayed as long as we wanted till we returned back, because we knew they needed us badly for combat. And it would just be a few days in the brig. We stole jeeps. We stole trains. We blew up barracks. We blew down trees. We stole the colonel’s whiskey and things like that.”

Jack Agnew, another member, added, “We weren’t murderers or anything, we just didn’t do everything we were supposed to do in some ways and did a whole lot more than they wanted us to do in other ways. We were always in trouble.” He couldn’t have said it better. The Filthy Thirteen might have been among the most dedicated in the military – they just refused to do anything unrelated to their mission.

D-Day landings

The Filthy Thirteen’s major engagement during WWII was during D-Day. They dropped into France with the 3rd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment and were tasked with either taking or destroying the bridges over the Douve. As a whole, the jump was a complete disaster for those deployed alongside the 3rd, as the majority were killed.

The Filthy Thirteen, on the other hand, didn’t go down quite so easily. Although roughly half of them were wounded, captured or killed, the remainder forged ahead, with McNiece in the lead. They slowly made their way toward their target. The only problem was they were assumed dead, so the US Air Force bombed the bridges, instead. However, some sources indicate they blew the structures up themselves.

What is confirmed is that they collected stragglers along the way to help with the liberation of Carentan.

Further engagements by the Filthy Thirteen

D-Day was devastating for the ranks of the Filthy Thirteen. NcNiece jumped with 20 paratroopers and came out with only two, losing “most of [his] men in the first two hours.” He was later assigned more, and they were deployed in future battles.

During Operation Market Garden, they were tasked with aiding in the capture and defense of three bridges in Eindhoven. This was their last official mission.

For the remainder of the war, the Filthy Thirteen were assigned to other squads or command posts. A small number, including McNiece, volunteered for the Pathfinders. To their surprise, they were parachuted into the fighting during the Battle of the Bugle. Despite the heavy losses sustained by most other units, the newly-formed Pathfinders only lost one member.

The Dirty Dozen (1967)

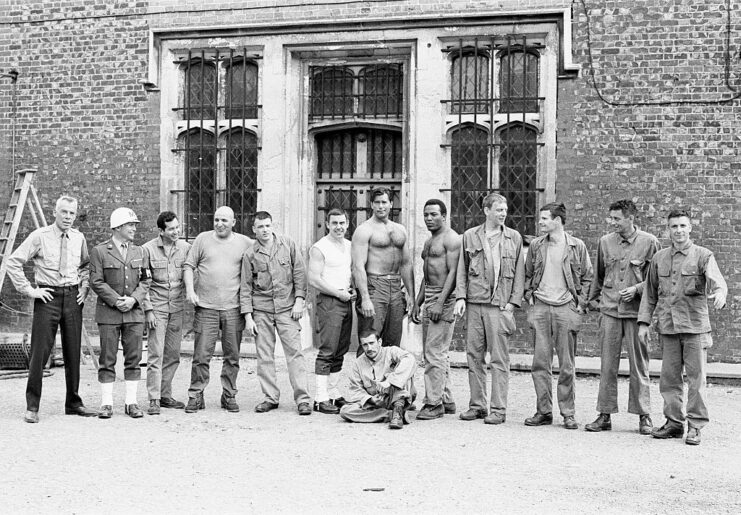

The story of the Filthy Thirteen was adapted by author E.M. Nathanson in his novel, The Dirty Dozen. After becoming a bestseller, Nathanson’s work was turned into the screenplay for the popular 1967 film of the same name.

While the Filthy Thirteen served as the inspiration for the story, it was by no means accurate. According to the daughter of John Agnew, about 30 percent of the film was true to life. Of one particularly real moment, she said, “The scene where they captured the officers, Dad said that was true and he really coordinated that.”

More from us: Clint Eastwood’s Iwo Jima Duology Accurately Depicts the Battle from Both Sides

The most important difference between the paratroopers and The Dirty Dozen, however, is that the men weren’t criminals – they just didn’t follow the rules. Other details that ring true were the lack of bathing, the unit’s failure to respect rules and their superior officers, and their constantly finding themselves in fights.