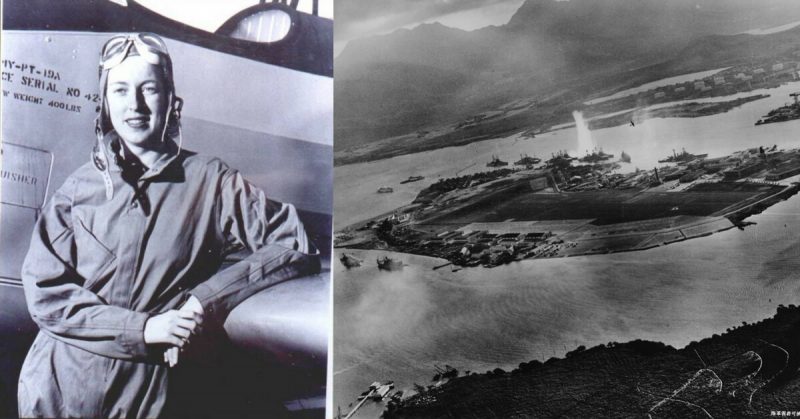

The first Americans to see the Japanese that fatal day they bombed Pearl Harbor were not on the ground. They were in the air, and one of them was a woman.

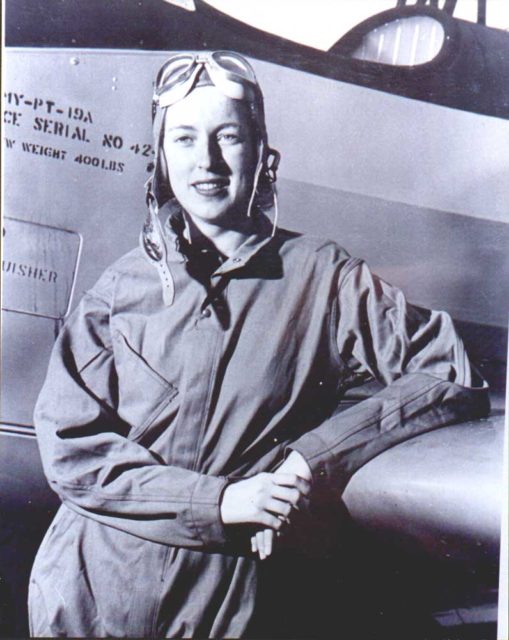

Cornelia Clark Fort was born on February 5, 1919, in Nashville, Tennessee to a wealthy family. Her father was a co-founder of the National Life and Accident Insurance Company, enabling them to live in a mansion on a vast farming estate.

Despite his accomplishments, Fort Senior had a terrible fear. One day, he gathered together his three sons and had them swear on the Bible that they would never, ever, fly. Cornelia was only five when it happened, so he did not think to make her take that vow. What girl would want to fly?

Socially isolated because of her family’s wealth and power, as well as shy among her peers, Cornelia was a bookish tomboy who was passionate about horses. Then at college, she learned there was more to life for women than marriage.

A friend invited her to Nashville’s Berry Field Airport for a plane ride. She agreed, and the rest is history. Cornelia found her passion in life and signed up for flying lessons that very day. Wisely, she kept it a secret from her family.

Aubrey Blackburn, her flight instructor, had a test for all his would-be students. He took them up in an open Interstate Cadet plane, flipped it over, then watched his upside-down students’ reactions. If they freaked out, it was lesson over. When he turned to look at Cornelia, however, she was grinning madly.

Shortly after, her father died, ending her need for secrecy. By summer, she became Nashville’s first woman to have a pilot’s license. By March 10, 1941, she became Tennessee’s second woman to hold an instructor’s license. Now came the hard part – who would hire a woman?

Her first offer came from Fort Collins, Colorado in a letter addressed to “Mr. Fort.” Cornelia nearly backed out, but her mother told her to write back and tell them the truth. The response was, “Dear Mister or Missis Fort. We need you, whoever you are.”

That got her a job with the Andrews Flying Service at the John Rodgers Airfield in Honolulu, Hawaii. America was already bracing itself for war, and Cornelia (a master of aerial acrobatics) wanted to contribute. Moving into the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, she started work on September 29 by exceeding current legal maximum flying times.

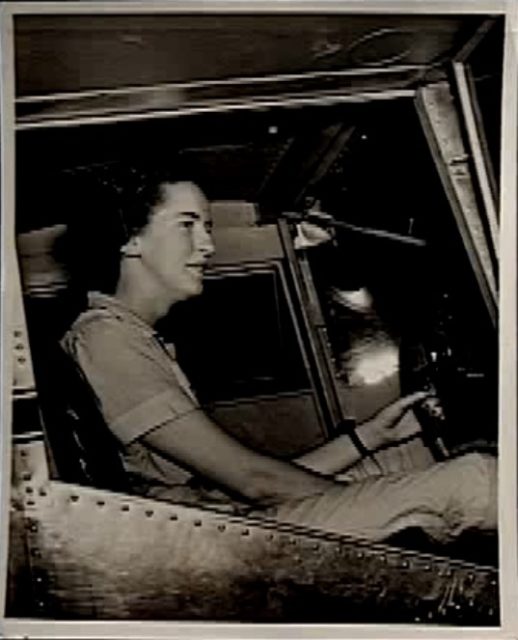

On December 7, 1941, the 22-year-old Cornelia took off before 7 AM with a male student known only as Soumala – a defense industry worker. Back then, there was no radio – only a “see-and-avoid” policy.

Just before 7:45 AM, Cornelia’s plane was aligning with a runway when a fighter plane headed their way. Thinking it was the Army Air Corps (who were supposed to avoid her airfield), she ignored it and focused on her student’s landing procedures. The plane, however, kept coming straight at them as if they were not there.

She grabbed the flight controls and pulled up sharply. The plane flew so close beneath them that the windows of their plane shook.

Cornelia’s eyes widened at what she later described as the “Red Balls” on the aircraft’s wings. She knew what they meant. What she did not understand was that something fell out of it. Moments later, an explosion shook the ground and plumes of black smoke rose up.

Bullets whizzed past as more planes headed their way. She continued the landing as bullets strafed them. They made it to the ground followed by Bob Tyce – the airport manager, who had just arrived in another plane.

Cornelia and her student ran into the hangar through a hail of bullets, shouting about the invasion. They were met with laughter until a mechanic ran in screaming that Tyce was bleeding to death on the runway. He did not make it.

Although Honolulu was on lockdown, the Forts used their political clout to get her back to the mainland on a ship. Reaching San Francisco on March 1, 1942, she became an instant celebrity which she put to good use by raising money for war bonds. She also gave lectures encouraging women to take up flying.

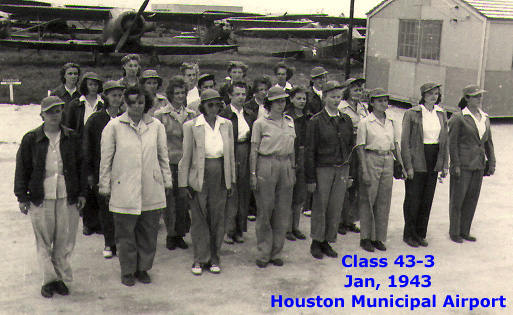

Her life changed again on September 6 when she received an offer she could not refuse. It was from the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) – precursor of the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP).

With male pilots in short supply, they needed women to fly planes from their factories to bases throughout the US. She would have to move to the New Castle Army Air Force Base in Wilmington, Delaware.

Cornelia did not hesitate and was determined to be the first to sign up. However, another woman flew there in her own plane – making Cornelia the second woman to join the WAFS.

Many women thought they were the only females who flew until they signed up. Most were wealthy, though a number were middle class. For the former, they had to get used to living in army barracks with few privileges.

Although the women already had flight experience, they were put through more training which took weeks. By contrast, men spent only a few days. The army believed women were slower to learn and they also paid them much less.

On March 21, 1943, Cornelia was part of a convoy with male pilots when one of them struck the left wing of her BT-13. She crashed south of Merkel, Texas, making her the first WAFS fatality.

Before leaving Hawaii, Cornelia knew there was a chance her ship would be sunk by a Japanese submarine. She, therefore, wrote her mother a letter, stating that if she should die:

“… I want no one to grieve for me. I was happiest in the sky, at dawn when the quietness of the air was like a caress, when the noon sun beat down, and at dusk when the sky was drenched with the fading light. Think of me there and remember me.”

After the war, the WAFS were disbanded, their records sealed, and their service forgotten. It was not until 1984 they were given the WWII Victory Medal, and only in 2009 that they qualified for the Congressional Gold Medal.