WWII had some very distinct theaters of war. When people think of the war in the Pacific thoughts, go to the sprawling jungles of Guadalcanal and wide stretches of ocean. Well, one campaign, now often glanced over due to the importance of other contemporary battles, was fought in the cold, stormy islands of western Alaska. Their strategic value has been debated, especially as the invading Japanese couldn’t do much of anything significant there, but if they were allowed to progress through the chain, the Pacific theater could have turned out quite different.

The Aleutian Islands form the long strand of islands off of Alaska’s southwest. Today they are part of Russia and the U.S. and they are about as sparsely populated today as they were during the war. There are a little over a dozen large islands and many smaller ones, with the tides constantly revealing and swallowing large chunks of the land.

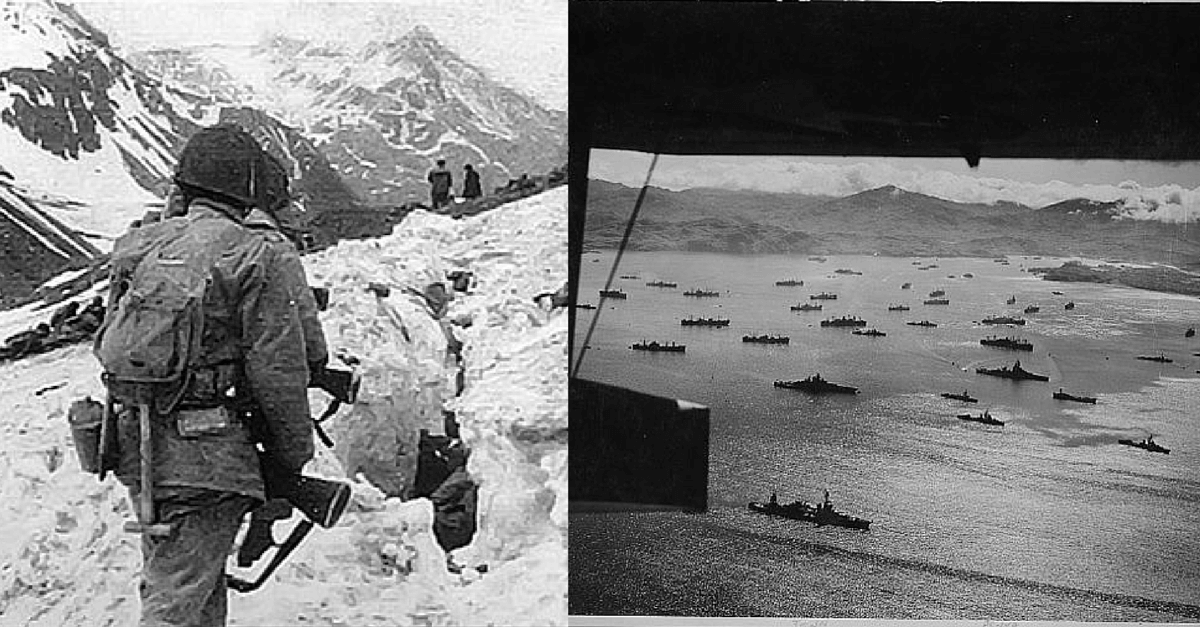

The islands lie exactly along the great Pacific Ring of Fire, the area of the most tectonic activity. This means that the islands have over 50 volcanoes and are prone to regular earthquakes. Their location is also the dividing line between the Bering Sea and the Pacific Ocean, and competing currents and weather systems. The islands’ average temperature hovers just a bit above freezing and heavy fogs and storms are common. The volcanic formation of the islands leaves little natural harbors or beaches. Instead, the islands look as if a mountain range simply rises straight from the water.

Despite the harshness of the islands, the Japanese still attacked to occupy them in 1942, raiding Dutch Harbor on June 4-5th and taking the islands of Kiska and Attu over the next two days. The heaviest casualties were during the harbor raids, as Japanese planes flew over the military outpost and caused heavy damage to ships and troop barracks.

The U.S. was as quick as they could be with a response. Soldiers were stationed on Adak Island, and an airfield was built out of steel plating nailed into packed earth. Heavy bombing runs were a regular occurrence over the Japanese-occupied islands. Planes took off and landed in constantly changing weather, and it was not uncommon for routine maintenance to be performed in knee-deep water.

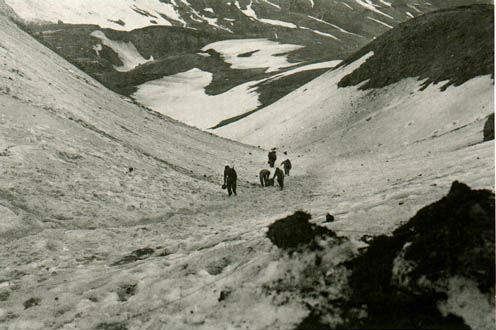

The turning point for the campaign happened off the islands, with superior naval tactics by the U.S. forces. In one action a U.S. submarine sunk one destroyer and severely damaged two others off Kiska. Another submarine sunk two pursuing submarine chasers before being overwhelmed and sunk.

The naval Battle of the Komandorski Islands was the boost the Americans needed to retake Kiska and Attu. With one heavy and one light cruiser and four destroyers, Admiral Charles McMorris was tasked with preventing the resupply of Attu. Unfortunately, he was outgunned as the Japanese had two heavy and two light cruisers four destroyers. Despite being outmatched, McMorris engaged and the fighting was surprisingly even, though more overall damage was taken by the American ships. Eventually, the Japanese withdrew, fearing U.S. air reinforcements. Though the U.S. ships sustained heavy damage, they achieved their goal, and plans were moved forward to retake Attu.

The U.S. set up an airfield on the island of Amchitka, a particularly harsh island just 50 miles away from Kiska. The terrible weather during the landing contributed to the sinking of one destroyer and 14 deaths.

On May 11th, 1943 after repeated bombings, the U.S. troops landed on Attu. Landings were on the north and south shores and successfully pinched the Japanese, but the advance was difficult due to the weather and terrain. Soldiers had to fight entrenched, practically buried, Japanese positions, but they also fought the weather. Many more men were evacuated from the island for disease and frostbite treatment than for death or wounds from battle. To make matters more difficult, many vehicles simply couldn’t operate in the steep and muddy terrain, and many pieces of equipment such as the radios malfunctioned in the field due to the constant blend of rain and snow and freezing and thawing temperatures.

Despite the hardships, the Americans had over 15,000 men including Canadian allies facing only 2,900 Japanese. If the Japanese were able to hold, however, the Japanese mainland was preparing to send a naval relief force of three carriers, two battleships and multiple cruisers and destroyers. Such a fleet would quickly turn the tables in the Aleutians and had the potential to push the Japanese attack even closer to mainland Alaska.

Less than a week after the fleet assembled, the Japanese in Attu found themselves pinned into Chichagof Harbor. With hopes of holding out fading, the Japanese led a sudden banzai charge at the Americans.

This attack was immediately successful and broke through American front lines. U.S. soldiers in the rear were suddenly fending off bayonets rather than waiting for word of victory. The banzai charge was eventually subdued and effectively ended Japanese occupation. A few small groups resisted, but soon enough they were killed or captured. Only 29 Japanese surrendered, and the rest were killed.

With Attu taken, the U.S. and Canadians set their sights on Kiska. Huge air and sea bombardments rocked the island before an invasion force landed. A Japanese mine struck the destroyer Abner Read, killing 70 men. Landing forces, uneasy about another battle as strenuous as Attu, were on edge. When American and Canadian troops ran into each other, friendly fire ensued and claimed over 30 dead. Over 100 more were killed or missing, due to various Japanese traps and the weather conditions. None were actually killed by the Japanese, however, as they had completely evacuated the island following the loss of Attu.

Though the Allies had to pay a high price for an abandoned island, the victory was still complete and secure. The Western U.S. was relatively safe from Japanese bombardment and North Pacific sea lanes were under control. The campaign also bought the Americans a crashed but operational Japanese Zero. The testing and examination of the Zero became a pivotal point of the war, giving engineers, generals and pilots better understanding of these successful Japanese planes. It has been described as one of the greatest prizes of the Pacific war.

Though the U.S. did not use the islands to attack the Japanese mainland directly, they were able to raid many islands to the north of Japan. These raids on the Paramushir and Kuril Islands caused minor damage but were a diversion enough to send tens of thousands of Japanese troops to defend against the possibility of a northern invasion from the Aleutians.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online