First World War

Born in 1892, Nehring entered the German army in 1911.

At the start of WWI, he was sent to the Eastern Front as part of XX Corps. There, he took part in fierce fighting against the Tsarist armies. On one occasion, while trying to break out of a Russian encirclement, Nehring’s platoon was unable to reach the regrouping point. Instead, he led them in capturing another Russian village, leading to a victory in the area.

Nehring was repeatedly wounded, including being shot in the throat. In 1916, he was transferred to the Western Front. There, he continued racking up scars and medals.

Between the Wars

Following WWI, eastern Germany was vulnerable to an attack from Poland. The Germans were forbidden to use regular army troops so the Poles took the opportunity to invade. Nehring recruited on behalf of the Volunteer Frontier Defence Force that faced the attackers. He then served as a company commander and reconnaissance officer.

Returning to the regular army, he rose through the ranks through a combination of study and skill. He spent time in both command and general staff positions. Influenced by his friendship with Heinz Guderian, he specialized in motorized warfare. Together they worked with General Lutz to develop Germany’s highly successful tank tactics.

Poland

In 1939, Nehring entered the invasion of Poland as chief of staff of XIX Corps.

The action provided valuable experience. He saw firsthand the effects of radio communication, discovering that it could be used to quickly redirect tank attacks, even shifting the line of attack for an entire operation. Like other commanders in the area, he also saw the problems of coordinating with slower moving and less flexible infantry groups. The result was a change in tactics toward specialist armored operations.

Nehring met Korovshin, a Russian tank expert, at a victory parade. Nehring had already hypothesized that the Russians could convert tractor factories to produce huge numbers of tanks if necessary. Korovshin kept his tanks out of the parade, preventing Nehring from seeing them.

France

During the 1940 invasion of France, it was Nehring’s plan that allowed Guderian to achieve one of his most decisive victories. Nehring himself served behind the lines, an unusual position for him, coordinating follow-up forces.

On May 20, Hitler ordered Guderian to set up a panzer group, consisting of multiple existing corps. Nehring was chief of staff for the group. Following its early swift successes, he was promoted to major general.

At the Front of the Russian War

For the invasion of Russia in 1941, Nehring was in charge of the 18th Panzer Division. The division was under-supplied, equipped with tanks that were unsuitable for Russia and the soldiers were not familiar with them.

Despite the drawbacks, Nehring had great successes, riding at the front of his division as it spearheaded drives deep into Soviet lines. He saw his theories of mobile warfare executed to full effect on the eastern steppes. His achievements included a 150-kilometer raid into the flank of a Russian army and the breaking of an encirclement at Suchinitshy.

The Desert War

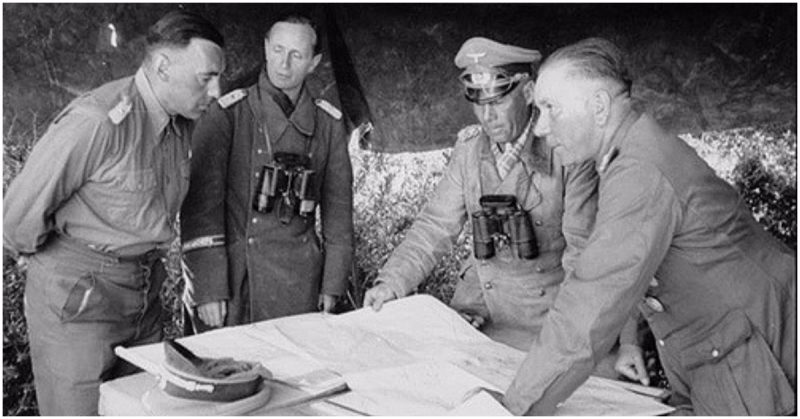

In February 1942, Nehring was sent to North Africa, where he took over the Afrika Korps as a lieutenant general.

Again, open spaces let Nehring make the most of his armored vehicles. He rescued Rommel’s forces when that commander became over-stretched, as part of an operation that led to the capture of Tobruk.

Riding with his front line tanks at the Battle of Alam Halfa, Nehring was wounded in the body and head.

He returned to action to face Allied forces that had landed further west, in Tunisia. There, using very limited resources, he created a bridgehead into which fresh troops were sent and to which Rommel could retreat from the east. He planned an operation at Tebourda that dominated the Allied formations there. By the time he left Africa in December, the link up with Rommel had been achieved.

Back to Russia

Returning to Germany, Nehring rebuilt the shattered XXIV Panzer Corps before leading it back to Russia. There, he was forced to redirect his troops in the face of a Russian counter-attack. He was once again wounded.

After recovering from his injuries, Nehring returned to the Russian front. He joined an army in retreat, driven back by the massed forces of the Soviet Union. He gained a reputation for holding broken fronts, as he repeatedly repaired and reinforced fractured German lines. His corps played the leading part in rescuing the 1st Panzer Army when it was surrounded.

Moved to the command of 4th Panzer Army, Nehring found a formation made up mostly of infantry, its tanks having been diverted to other work. Despite the absence of his preferred troops, he held back another Soviet offensive.

Last Days of the War

In October 1944, Nehring resumed command of XXIV Panzer Corps. The corps was now at Bardiyev in Slovakia, as the German retreat took them back out of Russia.

When Soviet forces smashed the German lines, Nehring took command of disparate troops surrounded by the enemy. The wandering pocket of German forces fought its way through a Russian encirclement then crossed Poland in a grueling 250-kilometer winter march, before joining the main German lines. Once again, Nehring had saved his men from disaster.

Nehring oversaw the retreat of much of Germany’s armor and commanded one of the last German panzer strikes of the war, surrounding and destroying Russian forces at Lauban.

When the war ended, Nehring led his troops west to Tabor so that they could surrender to the Americans instead of the Russians. After two years as a prisoner of war, he was released in 1947.