In the south of Berlin, there is a massive pillar; one of the few remnants of the Nazis’ attempts to make Berlin the capital of the Thousand-Year Reich, equaled only by Egypt, Babylon, and Rome, it now sits amongst shabby, peach-colored residential blocks.

The monstrous concrete structure has a 21-meter radius and weighs the same as 22 Airbus A380s. It rises above the ground over four stories tall and extends a further 18 meters into the ground.

The Schwerbelastungskörper, or “heavy load test structure,” was built to simulate the weight of one of the four pillars of the planned 120-meter-tall Triumphal Arch. The Arch would have stood on the north-south axis of Germania, and this pillar would have been on its northeastern side.

“Berlin’s swampy ground was seen as a potential hindrance for such a massive structure, so the engineers of the German Society for Soil Mechanics were commissioned to check the extent to which it would have to be reinforced,” says Micha Richter, a Berlin architect and leading member of Berlin Underworlds, an association that holds tours of historic sites across – and mainly underneath – the city. “It’s 12,650 tons of concrete were poured over seven months in 1941,” he says. French POWs were among those deployed in its construction.

Berlin historian Gerlot Schaulinski, who curated the Mythos Germania exhibition, says that the cylinder exposes the flaw in peoples’ view that Germania’s architectural plans were somehow detached from the atrocities committed by the Nazis. Instead, a close look at the methods used to construct the cylinder shows precisely the inhumane methods the Nazis used.

There is a close relationship between the buildings in Germania and the concentration camps. Many camps were built near quarries and the prisoners used to get the stone for the many buildings. Sachsenhausen was built near a planned brickworks plant. Tens of thousands died extracting stone or baking bricks for Germania. In Berlin, 130,000 POWs were put to work on construction sites for Germania.

The demand for labor was so great that the police were tasked with rounding up male beggars and tramps and other “undesirables” to put to work.

Ordinary Berliners also felt the effects of Germania. Many were forcibly moved to make room for the new city. Often they were given homes left empty when their Jewish owners were moved to ghettoes or concentration camps. Germania was used as a reason to drive Jews from their homes even before the pogroms in 1938.

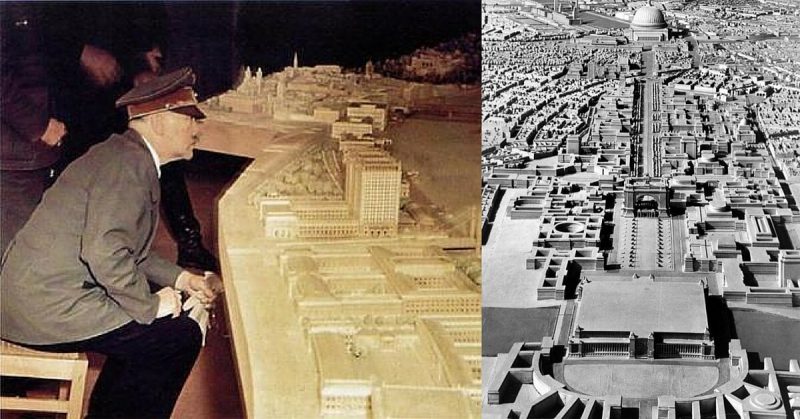

Had they been able to fulfill their vision, Hitler and his general building inspector, Albert Speer, would have altered the city beyond recognition. Large sections of Berlin would have been wiped out, including between 50,000 and 100,000 houses. Old structures like the Reichstag and the Brandenburg Gate, large structures by current standards, would have been dwarfed by the proposed buildings.

Welthauptstadt Germania, World Capital Germany, is often believed to be the official name given by the Nazis. That might not entirely be true.

“The name only emerged after the publication of Speer’s 1969 memoirs, Inside the Third Reich, and is based on casual remarks made, we believe, just twice by Hitler in conversation with a close circle of acquaintances,” says Schaulinski. “It combines the image of a visionary city of the future with that of a megalomaniac dictator. Now, ‘Germania’ stands for the hubris of the Nazi system and the failure of those big plans, because it only exists in drawings and model images.”

Schauinski points out Speer’s use of the name served him well in his postwar portrayal of his role in the project. “It supported his attempts to prove the strength of Hitler’s allure and why Speer – the architect, the artist – was so taken in by his egotism. It serves to divert our attention from architectural castles in the air and therefore manages to purposely blank out the criminal consequences of the project.”

Recent years have shed light on new details about Germania. Speer drove Jews from their homes and actively supported deporting Jews and others to concentration camps. He cooperated with the SS to ensure the slave laborers produced the building materials he needed. His own father called him crazy for his extraordinarily ambitious plan.

“Amid the aspirations to tear down and rebuild large parts of the capital, visions and crimes were inextricably linked,” says Schaulinski.

Evidence exists to suggest that Hitler started mapping out his plans as early as 1926, creating two postcard-sized sketches of the Great Arch. He envisioned it as a reinterpretation of Germany’s defeat in World War I. It would have been engraved with the names of the 1.8 million German dead from that war.

On the fourth anniversary of his rise to power, Hitler created the Inspector General of Buildings (GBI) and made Speer the head. The GBI’s mission was to plan and organize the redevelopment of Berlin.

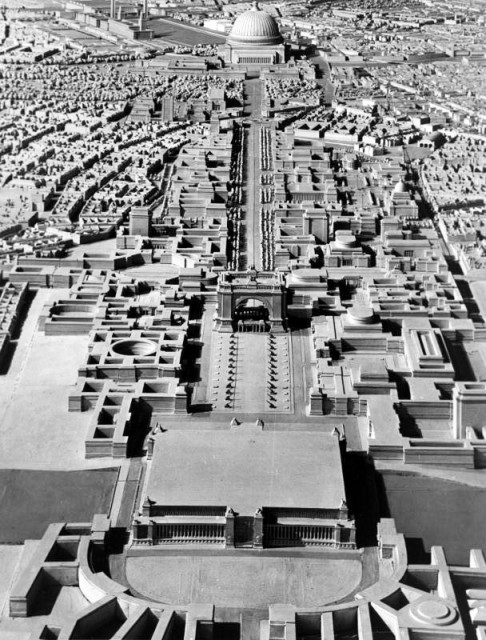

The plans were centered on a seven-kilometer north-south avenue linking two railway stations. The crown jewel of the city would be the Great Hall, whose dome would have been 16 times taller than that of St. Peter’s in Rome. It was to be the largest covered space in the world. The planners even worried about how the breath of the 180,000 it would hold would affect the atmosphere inside.

Connecting the Great Arch and the Great Hall along the avenue were to be new buildings for business and civic use. The avenues would be wide enough for parades of marching troops. Plans also included an artificial lake, a large number of ornamental Nazi statues, new roads, tunnels, and autobahns.

The scale is difficult to fathom, but it is clear that Berlin would have been transformed from an attractive place to live to a place designed for the state to show itself off. The scale would even have reduced Hitler to a spec when he addressed crowds from the Great Hall, a concern for some of his advisers.

Architects and urban planners have studied the plans and determined that it would have been a nightmare to live in. It was hostile to pedestrians, requiring them to regularly go underground to cross streets. It had a chaotic road system, since Speer did not believe in traffic lights or public transportation. Citizens would have been both impressed and inhibited by the towering buildings.

Schaulinski refers to a sculpture made by the Colombian artist Edgar Guzmanruiz in 2013 which is on display at Mythos Germania. It gives a good impression as to how the city would have looked. Guzmanruiz placed a transparent Plexiglas mold of Germania over a model of modern-day Berlin.

Schaulinski jokes that the current chancellery building, criticized for being oversized when built in 2001, looks like a garage next to the Führerpalast. The Reichstag building looks like an outhouse.

If you would like a hint of the scale, you can visit Berlin’s Olympic Stadium, Tempelhof airport or the former Reich Air Transport Ministry (now the Finance Ministry) for examples of Nazi architecture. The 17th of June Street, an avenue running east-west from the Brandenburg Gate, still has double-headed street lamps designed by Speer.

There is also the Siegesäule, or Victory Column, on the opposite end of the avenue at the Grosser Stern, which was moved from the square in front of the Reichstag to make way for a parade ground.

Originally unveiled in 1873 to mark Prussian victories, it was lengthened at Hitler’s request by adding another drum to the pillar. In the southern city of Stuttgart are further traces of Germania: 14 travertine columns made from “Stuttgart marble” for the planned Mussolini Platz in Berlin, but never delivered after the war blocked their transport. They now ring the border of a waste-incineration plant.

It’s the concrete test load pillar, however, that is possibly the clearest reminder of what Hitler and Speer had planned. Many would have liked it to have been destroyed after the war, but its size makes that impossible. It was used as an engineering test site until 1984.

Recent efforts have tried to turn it into everything from a climbing wall with a cafe at the top to a car showroom. Campaigners fight to preserve it as a reminder of what might have been. Thousands of visitors now visit it on guided tours every year. “It shows better than anything how it was a project where no compromises were to be made,” says Richter.

Next to the concrete cylinder, there is a 14-meter-tall viewing platform. From there you can see across the city. “This is the best impression you really get of just how crazy the Germania project was,” Richter explains. “On the plans, it all looks fairly flat, but here you see the extent to which they planned to completely change the topography of the city.”

The ground level of the Triumphal Arch site was to have been raised by 14 meters, “creating an optical illusion allowing a stage-managed view of the Great Hall, the prime object on the north-south axis, within the arch,” Richter says. The test structure would have been buried underneath the elevation and sealed by the arch, which would have stood three times as large as Paris’s Arc de Triomphe. It was just one small section of the plans to transform the city into an imposing metropolis.

It’s a mistake to see Germania as something that could only exist in theory, says Wolfgang Schäche, an architectural historian and expert on Germania.

“It was never a utopia, rather a very concrete, ideologically loaded projection of architecture and urban construction. All the ideas were checked by engineers and the best constructors of the time, and the Germania project had the support of an entire elite of German building experts who were actively involved in it, so that there is next to nothing – even the Great Hall – which would not have been technically feasible,” he says.

The Allied bombing attacks actually assisted by clearing large sections of the city. One of Speer’s senior staff members, Rudolf Waters, wrote in his diary: “Today once again the destruction by the allied bombers has assisted us greatly in our planning efforts!”

It was impossible to keep a scheme as grand as Germania a secret. Still, most details were kept from Berlin’s citizens. Even architects working on one structure would have no idea of the other buildings intended to be built near theirs. The press was tightly censored by the GBI.

There was a trio of political satirists called Die Drei Rulands who managed to make fun of the town planners from the stage of a leading cabaret venue. One of their musical numbers addressed plans to reroute the River Spree to accommodate the Great Hall. “Yes, through Berlin it still flows, the Spree / But from tomorrow it’ll go through the Charité,” a reference to the city’s largest hospital. Unsurprisingly, in January 1939, they were slapped down with a lifetime performing ban by propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels.

Ironically, the war diverted resources and attention away from Germania, including Speer’s after his appointment to minister of armaments and war production. Planning would have been high priority after the war. Expenses were never discussed because it was expected that they would take resources from the nations they conquered.

Speer and his planning department once visited Horcher, a popular restaurant for the VIPs of the day. One of them was overheard to say, “Normally an authority has to shape its spending according to its income. We’re able to do precisely the opposite!”

While Germania seems like a distant memory today, it still has a hold on the city to some extent. The “new Berlin” government district was built on the precise opposite axis to where the Great Hall was to have stood. Architects described this as “historical decontamination.”

There is an area in Tempelhof-Schöneberg that has been the source of strife between renters and the government.

Starting in 1938, the authorities bought about 1,000 properties worth 200 million Reichsmarks at a price fixed by them in order to prepare for the building of Germania. “They were marked ‘for destruction’ to make way for the so-called Great Road between the Triumphal Arch and the Great Hall,” according to Richter. “The residents were given similar properties elsewhere in the city and Jewish residents were moved in temporarily before they were deported to concentration camps.”

With property prices in Berlin currently rising exponentially, the present government is sitting on a gold mine, as the properties were never destroyed. The government recently announced that they would sell the properties to the highest bidder. Residents are angry that they might be pushed out of their homes by increasing rent. It looks like the legacy of Germania’s grandiose plans still lives on.