For all but fringe debaters on the subject, the book is closed. The horror and death caused by maltreatment or murder in German, Japanese and Russian prisoner of war (POW) camps stains the history of these countries red, and is still painful for many, on all sides of Word War II, to even mention.

However, over the years, controversy has lingered over another group of camps. Many still claim that these camps were another war crime, this time committed by the Americans, under the command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower: the Rheinwiesenlager.

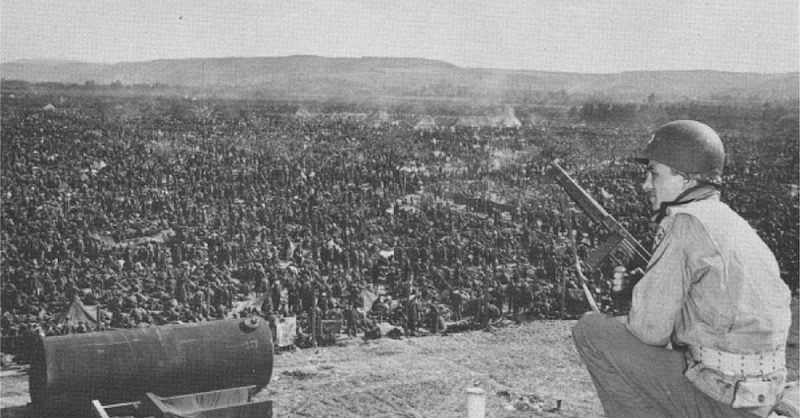

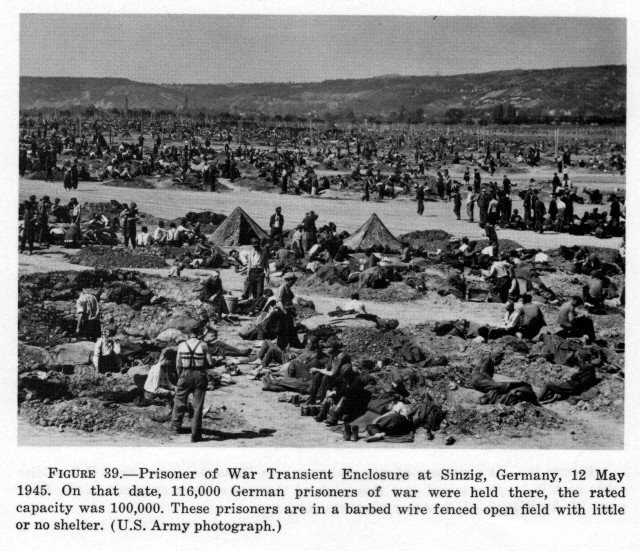

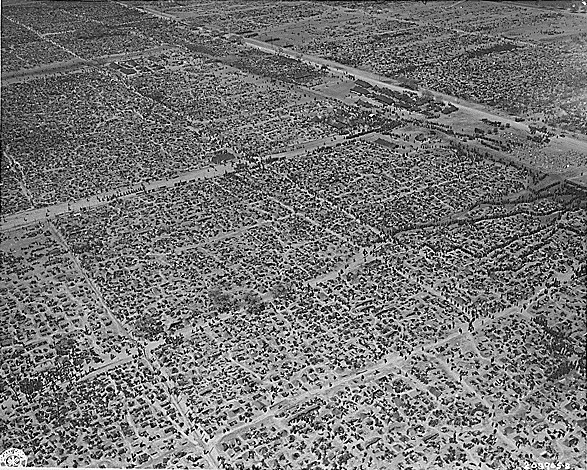

The Rheinwiesenlager were a group of American prison camps built along the Rhein river in April 1945 as the Allied Forcers were taking control and occupation of Germany. Around half of German soldiers captured in the West at the end of the war were placed in these camps. Most of the rest were placed in British and French custody.

It is certainly true that some facts about the Rheinwisenlager are shocking, the behavior of some of the Allied troops atrocious. These facts and their greater context will be presented along with the conclusions of historians and experts who have dived deep into this subject and the controversy around it.

There were 19 camps built in total, housing between 2 and 3 million prisoners. Some of these camps were turned over to British control in June, as they were in the “British Zone” in post-war Germany. Over 180,000 prisoners were sent to France at the request of the Charles de Gaulle’s government for forced labor. By September 1945, most of the Rheinwisenlager camps were closed.

The camps were beyond overcrowded. Prisoners mostly slept without shelter, exposed to the elements. Rations were generally between 1000 and 1550 calories per day. There was often little or no access to clean drinking water. Thousands died. How many thousands depends on who you ask. Regardless, given the facts, these camps did not hold up to the conditions mandated by the Geneva Convention.

This issue was circumnavigated, however, by a decision made in 1943 to declare German soldiers taken prisoner not as POWs, but as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF). With this characterization in place, things like lower rations and poor living conditions were inflicted without officially breaking what amounted to a binding international treaty.

Much of the controversy over these camps is centered around a book published by James Bacque in 1989 titled Other Losses. Bacque, a fiction writer, and amateur historian, found himself investigating what he saw as very disturbing deception and grievous disregard for life that lead to the death of probably over 1 million Germans.

Bacque posits that Eisenhower, out of a spirit of vengeance denied the DEFs food that was readily available throughout Europe and through the offers of the Red Cross.

With all the sweeping and horrifying claims made in Bacque’s book, a conference was held at the Eisenhower Center of the University of New Orleans to examine the history of the Rheinwiesenlager. The conference was attended by several historians and experts from America, Canada, Britain, Germany, and Austria specializing in that period of post-war Germany.

One attendant (who worked at the Eisenhower Center), Stephen E. Ambrose, wrote a summary of their findings in the context of Bacque’s claims.

Their first conclusion was in line with Bacque: that German prisoners were beaten, had water, food and mail withheld, and lived in exposed, over-crowded conditions. However, on almost everything else, they disagreed with Bacque. As Bacque claims that Eisenhower hated and wished to punish Germans, the conference cites numerous sources that show a true effort to rebuild Germany. An understanding of the difference between the German people and the Nazi’s that committed atrocious crimes, and that most of the policies that can be construed as vengeful came from higher up in U.S. Command than Eisenhower.

They did find that rations were kept frighteningly low for the DEFs and that the Americans did, in fact, prevent Red Cross aid and inspection of the camps. They find this more understandable in the greater context, however.

In April 1945, Eisenhower wrote to the Combined Chiefs of Staff of the Western Allies that the food situation in Germany was going to be desperate and that much needed to be done, and fast, to prevent starvation and chaos throughout the country. As Germany surrendered, and the occupation began, more slave laborers were freed than expected, more German soldiers surrendered than were expected as well, and around 13 million German civilians fled from the Russian occupied zone into the West.

In total, 17 million more people than Eisenhower expected when he saw the situation as desperate, now needed food as well.

The situation Eisenhower faced in the American occupied zone of Germany was very grim, as it was for the rest of Germany and much of Central and Western Europe. The reason the Eisenhower Conference cites for the tough rationing in the camps is that the General didn’t want to feed the prisoners more than the civilians or displaced people in a famine that affected the entire region’s food supplies for years to come.

In Ambrose’s summary of the conference’s findings, he writes that Bacque misreads, misinterprets, and even ignores much of the documentation of the Rheinwiesenlager. Bacque claims the American’s used the category of “other losses” in their records of prisoners to hide the deaths of some one million people.

Ambrose writes that hundreds of thousands of people under this heading that Bacque supposed dead were actually young boys and old men from the Volkssturm (People’s Militia) who were released. These, along with those transferred between different zones in Germany which Bacque didn’t mention, debunk the idea that so many thousands in “other losses” were wide-spread murder and death.

In total, it is thought that the mortality rate in the camps was as high as one percent and that no more than 56,000 German prisoners died.

The Rheinwiesenlager were not the worst camps to be held as prisoner in, during and after WWII, though the American’s could have been much more humane in their treatment. Mostly, the tight rations often blamed for the deaths of thousands of German prisoners were the result of mass hunger in most of Europe at the end of the war.

In 1945, Eisenhower said that “The success or failure of this occupation will be judged by the character of the Germans 50 years from now. Proof will come when they begin to run a democracy of their own and we are going to give the Germans a chance to do that, in time” (Ambrose).