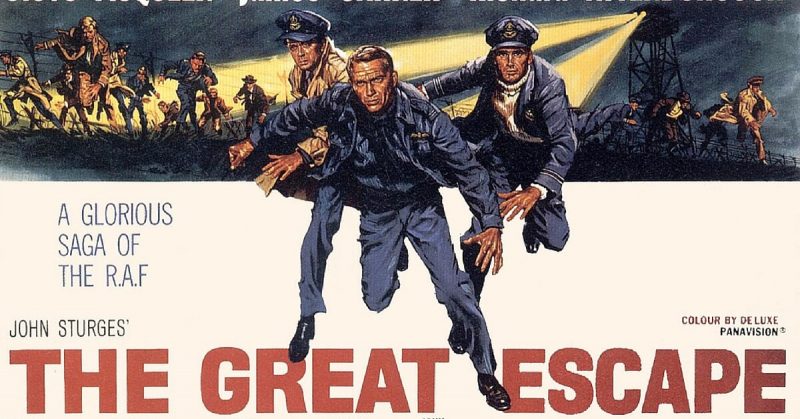

In 2006, a poll in the United Kingdom was done to determine which old family film TV viewers would want to watch in Christmas. Taking the number three spot overall, and number one for men, was the 1963 World War II epic The Great Escape.

Still beloved in the UK after many decades and despite the broad “Americanization” of the actual events the movie portrays, it is a truly classic war film crafted in the style of the age. That age in Hollywood was a far different one than today.

If The Great Escape was made in the present day, thrown onto the big screen in 2016, we would probably expect a very gritty opening scene—featuring the capture of one of the air force officers who escapes from the German POW camp later in the film or perhaps a dark, rainy night where they are led into the prison.

Instead, in an era much closer to post-war revelry, pride, and patriotism, the film opens with a sequence showing German military trucks carrying prisoners through the sunny German countryside with an uplifting, somewhat marshal, but certainly overall optimistic soundtrack playing.

The sequence ends with the trucks pulling into the camp to unload the prisoners who are played by U.S. and British stars like Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough, James Garner, and Charles Bronson. We are introduced to the main Allied air force officers being held and their German guards (who display varying levels of authentic to clearly fake accents). Then the action gets underway, displaying some politics between the prisoners and their collaborative effort to dig three tunnels for a mass escape.

Many details in the film were spot on. Stalag Luft III, the POW camp of Sagan, Silesia, then in Germany, was re-created with good depictions of the camp grounds, fences, towers, and guards. The film was shot in Germany, though almost entirely in Bavaria. Most of the Silesia region became part of Poland following World War II.

Several of the actual prisoners from Stalag Luft III were consulted as technical advisers for the film. They asked the producers not to include any details of the help they received hidden in gift packages from their home countries, in order to not compromise escape attempts from any possible future POW situations. This also shows the difference in the times between when the film was made and present day. Who would consider such precautions when making a film now?

Former Royal Canadian Air Force Pilot, mining engineer, and Stalag Luft III prisoner Wally Floody was both the inspiration for Danny Valinski, the “tunnel king” played by Charles Bronson, and a technical adviser to the film. Thus, many of the details of tunnel construction by the prisoners were very well done, including a hand-operated air pump for the tight spaces that ran over 100 meters when completed.

Sadly, with the movie’s emphasis on U.S. and British officers for commercial purposes, the vital role of officers from other countries in the actual events are lost. Floody himself was one of 150 Canadians in the camp who participated in constructing the tunnels. The actual camp held over 1800 prisoners, 600 of which, from over a dozen countries, worked on the tunnels—the most coordinated and ambitious escape attempt of the war.

Perhaps the most glaring revision of nationalities in the film was the amending of the fact that all the U.S. officers were transferred to a different camp many months before the escape took place, but were clearly a part of it on the screen.

Richard Attenborough (who later played in the beloved 1993 film Jurassic Park) acted the part of Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett, codename “Big X.” Though most of the characters in the film were carbon-copies of the real men, some were based on real people and several were composite characters, featuring many true details. There was a “Big X,” but his real name was Roger Bushell. He had escaped German custody twice since being captured in 1940 and even made it to within a few hundred yards of the Swiss border before being captured. When he was transferred to Stalag Luft III, he headed the group digging the tunnels as depicted in the film. Bushell even had scarring around his left eye featured in Attenborough’s makeup for the film, though in the film it is seen on the wrong side of his face.

Spoiler alert!!!

After 76 prisoners escape in the movie (the same number as in the true events), 73 are recaptured and three escape. The three successful men are British, Polish, and Australian in the film, but were Norwegian and Dutch in real life. Like the actual, tragic reality, 50 of the recaptured prisoners are shot, though in very different circumstances (gunned down en masse while “stretching their legs” before a long drive back to prison vs. the reality of more traditional executions).

The movie depicts the German Kommandant of the POW camp as visibly upset and ashamed when he informs a British officer that 50 of his fellows were shot and killed while trying to escape. It is true that the Kommandant who took over the running of the camp after the escapes, Oberst Franz Braune, thought the killing of the 50 escapees to be horrific and allowed the men still held there to build a memorial for their comrades, which still stands today.

Before recapture, the movie shows some truly thrilling and classic chase scenes. One, done on the request of motorcycle junky Steve McQueen, features his character, Captain Virgil Hilts, the “Cooler King,” racing through the German countryside on a motorcycle chased by German troops. All but the final jump in the sequence has McQueen performing his own race and stunts.

Depending on which critic you ask, the movie was either a great war epic with good, clean, and thrilling escapism or a long drawn-out Americanized snoozer that gets exciting towards the end and then becomes abruptly tragic. Depending on the value one places on historical accuracy, The Great Escape varies in how one could see it as honoring the actual men and events. But, for a mostly fun and spirited old war flick, it’s not a bad show.

By Colin Fraser for War History Online