The battles of Iwo Jima and Midway are well remembered as two of the most important engagements in the Pacific Theater of the Second World War. However, it can be argued that the months-long Guadalcanal Campaign in 1942-43 was nearly as critical, and the following are six facts that show it was one of the turning points of the conflict.

Guadalcanal Campaign

Guadalcanal, one of the Solomon Islands, was the first offensive campaign by the Americans in the Pacific Theater of World War II. Following the successes at Midway and the Coral Sea, the decision was made to move from a defensive stance to an offensive one, with the hope being to break Japan’s territorial control in the South Pacific.

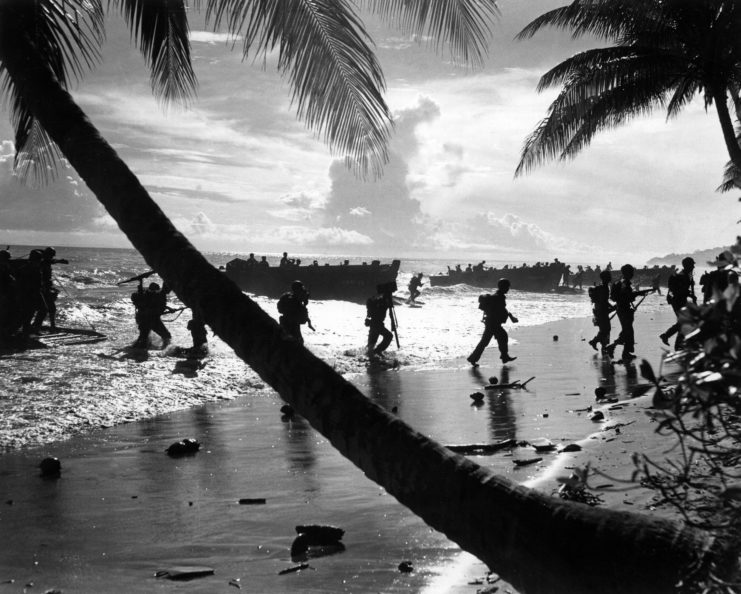

On August 7, 1942, a force of 6,000 US Marines landed on Guadalcanal and the nearby Florida Islands, with additional troops arriving on the shores of Tulagi. Supported at sea and in the air, they caught the estimated 2,000 Japanese troops stationed on Guadalcanal off-guard. However, they were quick to regain their strength, leading to months of fighting, both on land and at sea.

Between the first landings and February 9, 1943, a series of engagements were fought as part of the Guadalcanal Campaign:

- Battle of Savo Island (August 8-9, 1942)

- Battle of the Tenaru (August 21, 1942)

- Battle of Edson’s Ridge (September 12-14, 1942)

- Second and Third Battles of the Matanikau (September 23-27, 1942 and October 6-9, 1942)

- Battle of Cape Esperance (October 11-12, 1942)

- Battle for Henderson Field (October 23-26, 1942)

- Matanikau Offensive (November 1-4, 1942)

- Koli Point Action (November 3-12, 1942)

- Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (November 12-15, 1942)

- Battle of Mount Austen, the Galloping Horse, and the Sea Horse (December 15, 1942-January 23, 1943)

When all was said and done, the Guadalcanal Campaign resulted in an Allied victory. However, it wasn’t without its casualties. The Japanese lost 31,000 men, nearly 40 ships and hundreds of aircraft. The Allies, while suffering less human losses (7,100), saw their naval and aerial forces heavily hit.

‘Operation Shoestring’

The United States had hoped to stay out of WWII, but things changed following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. While leadership would have liked to have been more prepared to take Guadalcanal, that wasn’t an option and, as such, the campaign was hastily put together.

Wanting to capitalize on the success of the Battle of Midway, Commander in Chief of the US Fleet Adm. Ernest J. King wanted to launch an assault on the Japanese stronghold as soon as humanly possible. However, 1st Marine Division Cmdr. Gen. Alexander Vandegrift wanted at least six months of training, knowing full well intel about Guadalcanal was scarce, at best. They had only a few maps of the island and the waters that surrounded it.

On top of this, the American forces in the region lacked the proper equipment – aircraft and ports, to be exact. King, however, was determined and thus didn’t heed these concerns, going so far as to say the landings would occur “even on a shoestring.” As such, troops jokingly nicknamed the mission, “Operation Shoestring.”

The weather was in the Americans’ favor

Following the Battle of Midway, the Japanese forces knew the United States would keep attacking, but they didn’t exactly know where the troops would strike next. Aircraft regularly flew reconnaissance around the Solomon Islands, but severe storms were brewing just as the US Fleet neared Guadalcanal.

The poor weather significantly affected the reconnaissance missions and the approaching troops went unnoticed. On the night of August 6, 1942, the Allies made their move, coming ashore in what became known as the “Midnight Raid on Guadalcanal.”

Every branch of the US military took part in the Guadalcanal Campaign

The Guadalcanal Campaign was unique in that it took place on land, at sea and in the air. As such, every US military branch that existed at the time – Army, Navy, Coast Guard and the Marines – were involved.

The US Marine Corps was responsible for the lion’s share of the fighting on the ground, but the men were unprepared for the hot and humid weather and harsh jungle conditions of Guadalcanal. Over the months of fighting, they grew mentally and physically exhausted, meaning they were more than pleased when US Army reinforcements arrived in October 1942 and January ’43.

The US Navy played the important role of transporting troops to Guadalcanal and providing support from the water, whether that be attacking Japanese ships or delivering supplies to shore. What’s more, it teamed up with the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) for aerial assaults and defense, which, along with aircraft manned by Marines, provided more than enough air support.

In regards to the US Coast Guard, its members were largely charged with ensuring the safe landing of troops and supplies on the island – one even received the Medal of Honor for his actions as the service moved into more of a ground support role.

Douglas Munro and the Medal of Honor

As aforementioned, the US Coast Guard was involved in aiding the Marine Corps during the Guadalcanal Campaign. For much of the offensive, the Japanese held the majority of the island, with the Americans only controlling the westernmost part.

Lt. Col. Chesty Puller was eager to get a foothold on the other side of Guadalcanal and Signalman Douglas Munro, along with his friend, Raymond Evans, volunteered to lead a group of unarmed landing craft to pick up the Marines and drop them off at points along the Matanikau River.

However, the group soon found themselves under attack, resulting in mass casualties. Both Coast Guardsmen volunteered to stay back while their comrades pulled out the injured Marines, using suppresive fire to mask the evacuation. While things overall went well, Munro was sadly shot in the head by a Japanese machine gunner and killed.

On May 24, 1943, US President Franklin Roosevelt presented Munro’s parents with a posthumous Medal of Honor – the only Coast Guardsman to receive the distinction. In his honor, three US military vessels have been named for him.

American air success set the tone for the rest of World War II

The American forces shocked Japan by destroying multiple aircraft carriers during the Battle of Midway, but their domination in the air throughout the Guadalcanal Campaign proved the prior engagement was no fluke. US Marine, Army and Navy aviators all participated in aerial combat and slowly, but surely took out a significant portion of the elite Japanese aircrews.

This domination in the air was crucial at Guadalcanal, but also had a trickle-down effect for the rest of the Second World War. So many of Japan’s best airmen were taken out, making it easy for the Americans to maintain air superiority in future conflicts.

Operation Ke: Retreating in secret

The Guadalcanal Campaign was devastating for the Japanese in several ways, from disease and starvation to battle wounds and deaths. As such, the decision was made to orchestrate a secretive retreat from the island, to prevent more casualties. Officially known as Operation Ke, it had the approval of Emperor Hirohito and involved Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and Army (IJA) personnel leaving Guadalcanal under the cover of darkness over three nights: February 1, 4 and 7, 1943.

To ensure the success of the operation, the Japanese began preparations that January. They changed their codes, to make it more difficult for the Allies to gather intelligence, and began building up their naval presence at nearby islands, which were believed to be the enemy’s way of diverting attention from action in the Solomons. The plan was then to bring support troops to Guadalcanal and move westward.

More from us: Johnnie Johnson: The Highest-Scoring Western Allied Air Ace of World War II

On high alert, the Americans didn’t make the Japanese evacuation easy, launching attacks on the retreating troops under the belief they were planning something. When they came across only sick and injuried enemy troops on February 8, it was finally realized that the build-up and movements of the previous weeks hadn’t been offensive in nature.