The Nazis had a “Master Interrogator” who was so good at getting information out of prisoners that he became a legend. His methods were so effective that the US ended up adopting them. He didn’t use torture, cruelty, or any of the other techniques that the Nazis were famous for, however. He used something so unusual, it was mind-boggling.

Hanns-Joachim Gottlob Scharff was never meant to be either a Nazi or their best interrogator. Born on December 16th, 1907 in Rastenburg, East Prussia to a wealthy family, his father was an army officer who died during WWI.

His maternal grandfather owned textile mills throughout Germany, so Hanns grew up in the family villa at Leipzig where he studied art. He also learned the family business, starting out with textiles and weaving before moving on to merchandising, marketing, and exporting.

To train him in sales, Hans was sent to Adlerwerke’s (a now defunct firm) South African branch for a year. He ended up doing so well that they made him the director of their overseas division – a role he served for the next decade.

He was a good salesman who knew how to handle people. While in South Africa he married Margaret Stokes, daughter of Captain Claud Harry Stokes – the British flying ace who scored five aerial victories in WWI.

In 1939, the couple and their children went back to Germany for a vacation when WWII broke out. So now they were stuck.

As a German citizen, he was drafted by the Wehrmacht (armed forces) who sent him to Potsdam for training. His final destination was to be the Russian Front, but Margaret had other ideas.

Since Hans was also fluent in English, she realized that he had a better chance of survival if he were kept as far away from the war front as possible. So Margaret convinced the authorities to use him as an interpreter.

A telegram was therefore sent to Hans’ unit, ordering his transfer to Interpreters Company 12 in Wiesbaden. It arrived the day he was to leave for Russia, but when he got to Wiesbaden, the Military Police tried to put him with another battalion headed for Russia.

So Hanns called on family connections which got him to Kompanie XII in Mainz where he began his training in military organization. They promoted him to lance corporal in 1943 and finally sent him to Wiesbaden where he was given the exciting task of doing paperwork.

Bored by the job, he jokingly told his superiors that he had calculated the cost of each hole his paper-puncher made (about 1¢). They weren’t amused, so he again explained that he was fluent in English and that his talents were being wasted.

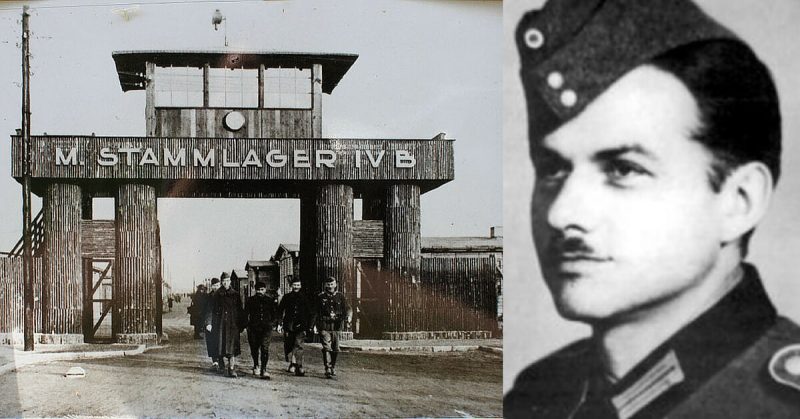

Impressed, they sent him to the Intelligence and Evaluation Center West at Oberursel, outside Frankfurt. The facility was where they interrogated all captured non-Soviet Allied soldiers, and it was there that he became an assistant interrogation officer to two men.

Hanns was not impressed with their techniques, however, seeing no value in brutality. Although the Germans had a list of approved and less-violent techniques, his trainers saw no reason to observe them.

Hanns, therefore, vowed that if he were in charge, things would change. They did in late 1943 when a plane crash killed the trainers. He was transferred from the Army to the Luftwaffe (air force), given an assistant, and put in charge of questioning captured US Army Air Forces (USAAF) personnel.

He wasn’t given a promotion, however, and so was allowed to wear civilian clothes. This impressed the American POWs who thought he had a higher rank than he actually did – setting the stage for what was to come.

New arrivals were scared, confused, and kept in isolation when not being questioned. Hanns got as much information as he could on the men, but divulged little, letting them believe he knew more about them than he actually did.

When they were being difficult, he told them that unless they could prove they weren’t spies, he’d have no choice but to turn them over to the Gestapo. Everyone knew of the latter’s reputation for sadism and were terrified by the prospect.

Hanns had another secret weapon – kindness. He would befriend them, bring them food, and take them on walks in the surrounding woods. Sometimes, he’d even take them to the local zoo. One POW was even allowed to test drive a plane. None tried to escape.

His method, now called the Scharff Technique, was made up of four strategies: (1) befriend the prisoner, (2) let them talk but don’t press them for information, (3) pretend to know everything, and (4) use confirmation/discontinuation.

Confirmation shows that you value the person, what they have to say, and enjoy their company. Discontinuation is the opposite. Hanns would switch between the two, rewarding cooperative POWs with the former and punishing them with the latter.

His methods were so effective that prisoners didn’t realize they were giving away valuable information. He once suggested to a prisoner that chemical shortage caused American tracer bullets to produce white smoke instead of red. The prisoner shook his head and said it was meant to be a signal of low ammo – valuable intel to the Wehrmacht.

On July 20th, 1944 Francis Stanley “Gabby” Gabreski, the famous fighter ace with 34 kills to his name, was shot down. Despite his best efforts, however, Hanns couldn’t crack the man, but they parted friends and reunited in 1983. In fact, most signed his guest book before being sent off to other POW camps, and met with him after the war.

In 1948, he was invited to the US to interrogate Martin James Monti – the USAAF pilot who defected to the Axis in October 1944. The US Air Force was so impressed by his methods that they’re still taught in interrogations schools today. Hanns eventually became an American citizen and devoted himself to art.

You can see his mosaics at the California State Capitol Building, the Los Angeles City Hall, and the Cinderella Castle at Walt Disney World, among others. Hanns died in 1992, but not before proving the old adage that you can attract more flies with honey than with vinegar.