n 1942, after a few months of fighting, only 300 of the original 1,000 men of Trautmann’s unit were still alive.

When American soldiers captured a German infantryman in a barn in France in 1944, little did they know that twelve years later he would be one of the most famous footballers in England. They also could not have imagined that he would be one of the only people in history to have been awarded with both Germany’s Iron Cross for valor, and the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE).

Trautmann was born in Bremen, Germany, in October 1923. Like many young Germans of his generation, he came of age during the time in which the Nazi Party rose to power, and as such he joined the Jungvolk (the junior arm of the Hitler Youth) at age ten. As a boy he excelled at sports, particularly soccer, handball, and dodgeball.

When the Second World War broke out, Trautmann was working as an apprentice to a mechanic. He joined the Luftwaffe in 1941, and while initially trained as a radio operator, he later became a paratrooper, serving in Poland.

After playing a practical joke on his sergeant, which went badly wrong and resulted in the sergeant getting burn wounds, Trautmann was sentenced to three months in military prison.

During his stint in prison he came down with appendicitis and had to be transferred to a military hospital. After this, he returned to active service, but transferred to the 35th Infantry Division. As an infantryman, he fought on the Eastern Front in Ukraine. He was promoted to corporal, and awarded with five medals for bravery and valor, one of which was the Iron Cross.

https://youtu.be/ZVt-Lq_-mls

Still something of a troublemaker, during his breaks from the fighting he enjoyed heading into towns and looking for trouble with Italian troops, with whom he would get into brawls.

His time on the Eastern Front, however, was difficult and stressful. His unit suffered massive losses at the hands of their Soviet adversaries. In 1942, after a few months of fighting, only 300 of the original 1,000 men of Trautmann’s unit were still alive.

He was then transferred from the Eastern Front to France, as part of a new unit made up of the remnants of other units that had been destroyed on the Eastern Front. His time in France was just as difficult as his time on the Eastern Front, though.

His unit was bombed to pieces, and he was one of the only men of his unit to survive the Allied bombing of Kleve. At one point he was buried under the rubble of a bombed-out building for three days.

At various times he was captured by both the French Resistance and Soviet troops, but he managed to escape from them. When, in 1944, almost his entire unit had been wiped out, he decided to try to get back home on foot. Because he would be regarded as a deserter by fellow German troops and probably be shot on sight, he avoided both German and Allied troops, who were equally likely to kill him.

He managed to evade Allied and German troops for a while, but his luck ran out when he was hiding out in a barn in France. Two American soldiers captured him, and after interrogating him had him march out of the barn at gunpoint with his hands up.

He thought that they were about to execute him, and thus made a break for it, bolting suddenly and jumping over a fence – only to land right in front of a British soldier, who promptly recaptured him.

This was to be Trautmann’s final escape. After this, he no longer had the will to try to break out any more, and became a prisoner of war in a POW camp in Essex in Britain. At the camp he was initially classified as a Category C prisoner – in other words, a Nazi. However, after some time this status was downgraded to Category B, which meant that he was considered rehabilitated from his former Nazi brainwashing.

After this downgrade in status, he was transferred to another, lower security POW camp in Lancashire, where he began doing farm work and interacting with local villagers in the area. Soon after the war ended, the British government offered to repatriate him to Germany, but instead he asked to be able to stay in Britain, a request they granted.

He had never forgotten his boyhood love of sports, and soon got back into playing soccer. He joined the amateur club St Helens, and very quickly developed a reputation as a superb goalkeeper, who played with flair and unorthodox tactics, and who seemed to have an unbelievable talent for stopping shots and penalties.

As his reputation grew, bigger clubs naturally began to take an interest in this remarkable goalkeeper they were hearing so much about. In the 1949 season, Manchester City, one of the biggest clubs in the country, offered him a contract, which he took. The fact that Manchester City was signing a man who just five years earlier had been fighting for Germany caused a great deal of controversy, though.

When the news of Trautmann’s signing was announced, 25,000 people gathered for a protest outside the club’s headquarters, shouting slogans such as “Nazi!” and “war criminal!”. Many of the club’s fans threatened to boycott the entire season. It was only through the intervention of one of Manchester’s senior rabbis, Dr. Alexander Altman, who said that Trautmann should be forgiven, that the protests began to subside.

Even so, Trautmann’s reputation as a former German soldier would trail behind him for a while, with supporters of the teams Manchester was playing against hurling abuse at him and calling him a Kraut and a Nazi. Sometimes it got so bad that it affected his concentration during the games, and he let in shots at goal that he normally would have stopped.

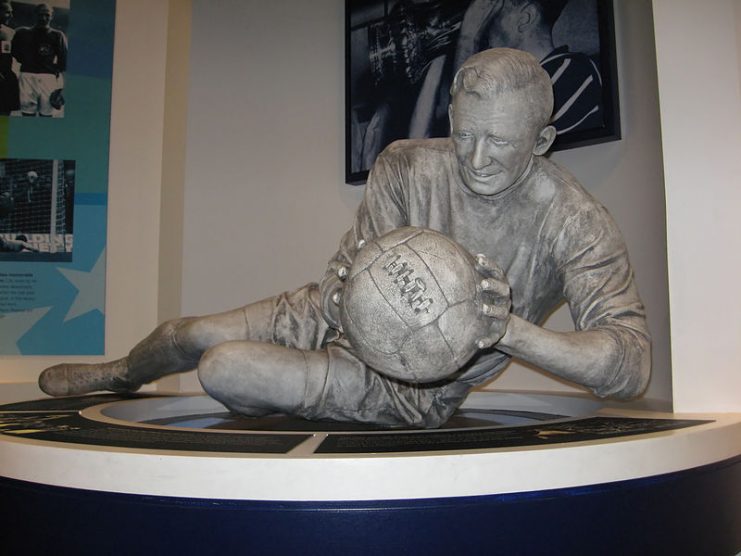

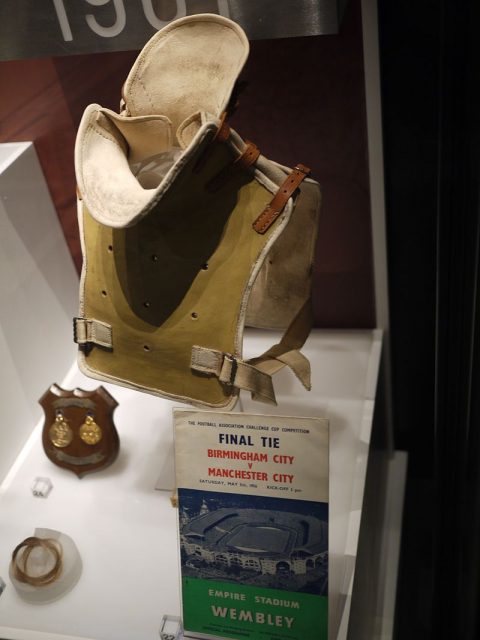

However, he soon overcame this challenge, and as spectators saw how talented he was, they became fans instead of enemies. One of his finest moments as a goalkeeper was in the 1956 FA Cup Final against Birmingham. With Manchester City leading 3-1, Trautmann made a heroic save, in the process colliding with Birmingham striker Peter Murphy.

The impact dislocated five vertebrae in his neck, but he continued to play on, saving a number of shots and allowing Manchester City to retain their lead and win the FA Cup. That year he also won the FWA Footballer of the Year Award, a prestigious honor, and in winning this award he became the first goalkeeper to receive it.

Tragedy struck shortly after this triumph, though, for his firstborn son was killed in a car accident just months after the FA Cup win. This tragedy affected him deeply, and this, combined with his injury, meant that he never again quite reached the heights of performance on the soccer pitch that he had prior to 1956.

He retired from soccer in 1964, and began coaching soccer instead. He eventually ended up working for the German Football Association, for which he worked as a development worker in poorer nations. This work took him to places such as Myanmar, Pakistan, North Yemen, Tanzania and Liberia.

He retired in 1988, and lived in Spain up until the time of his passing in 2013 at the age of 89. In 2004 he was awarded the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE), which made him the one person in history to hold both an OBE and the Iron Cross. The Daily Mail listed him as the 19th greatest goalkeeper of all time, and in 2018 a movie, The Keeper, was made about his life.