“The family considered him the nice uncle,” said Katrin Himmler during an interview with the Neu Westfälischer newspaper in 2010.

She shares a surname with the infamous leader of Hitler’s terror organization, but who is Katrin Himmler precisely, and what is her relationship to the Reichführer-SS Heinrich Himmler?

In short, Katrin Himmler called her great-uncle Heinrich Himmler the “murderer of the century” in her book Die Brüder Himmler: Eine Deutsche Familiengeschichte (The Himmler Brothers: A German Family History). And she would know because she is the granddaughter of Heinrich Himmler’s younger brother, Ernst Himmler.

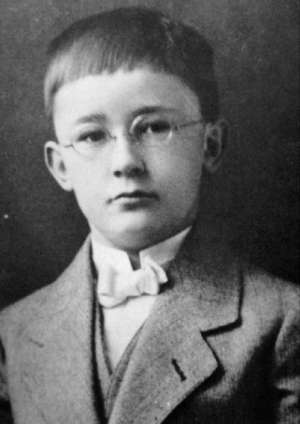

“Heini” or Heinrich Himmler was the second of three sons. His father, Joseph Gebhard Himmler, was a schoolteacher, and his mother, Anna Maria Himmler (née Heyder), was a devout Roman Catholic.

His brothers, Ernst and Gebhard, were considered apolitical technocrats and engineers who had little to do with Nazism. Or so it was thought for many years.

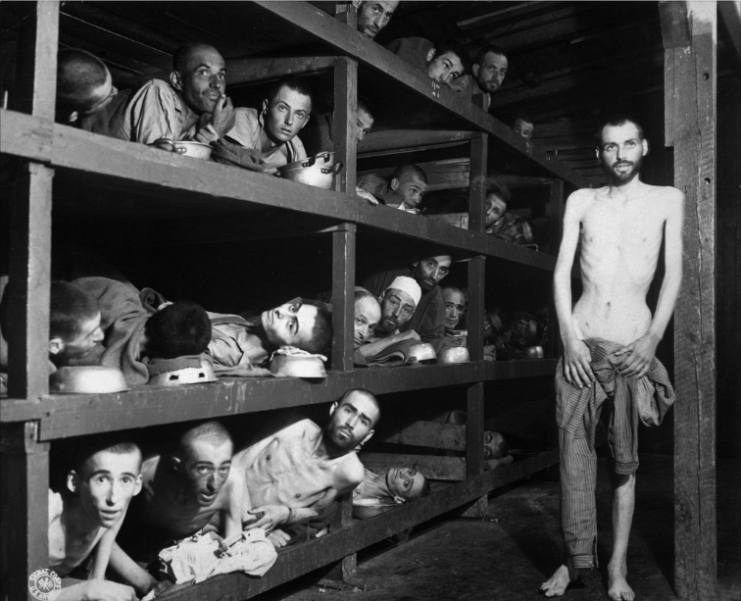

At first, Heinrich Himmler was believed to be a non-entity and a relatively normal boy, but he became a monster that orchestrated the killing of millions of people during the Second World War.

But can a monster come from a normal family?

“Meanwhile, I know, these are such damn normal people, and that’s the scary thing,” said Katrin Himmler during an interview.

In The Himmler Brothers, she describes how National Socialism inspired Gebhard and Ernst from an early age. She also portrays how the family profited from the rise of their infamous relative, Heinrich.

The path to her book was long and painful

Katrin Himmler’s parents bombarded their two daughters with enlightened literature on the National Socialist regime from very early on. However, they never discussed it much beyond that. The daughters had to deal with the information themselves, which they did in various ways.

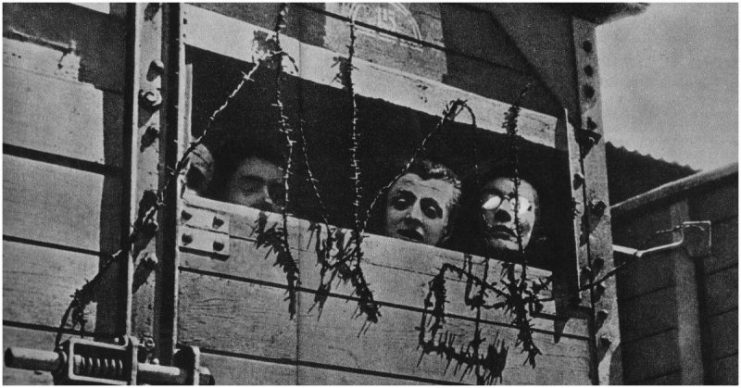

When she saw the four-part 1970s American TV series Holocaust aged 11, Katrin Himmler had nightmares for days. “I felt terrible,” she explained. Her sister, who is younger by one year, was able to push away the topic, but not Katrin.

Katrin Himmler, a political scientist, gradually approached her family history over the course of many years. First, she dealt with the resistance against National Socialism, then with the victims, and finally with the perpetrators.

“Eventually, I was brave enough to go to events with Jewish witnesses and even introduce myself with my infamous surname,” she said in an interview with the Frankfurter Allgemeine in 2005.

She then started a research project concerning the descendants of second and third generation perpetrators. This was always done at a distance from her own family. However, while conducting a university seminar on the grandsons of the perpetrators, she finally realized that she had to include her relatives.

Her father initially supported her in this undertaking and started to tell her everything he knew from before.

However, his zeal soon waned when he realized how little the picture of his father, Ernst, which his daughter had uncovered through diligent research, corresponded to the cherished ideas of the apolitical engineer in the Reichsrundfunkgesellschaft (Reich Broadcasting Corporation).

Even one of Gebhard’s daughters did not want to say anymore when she realized how deeply her niece had begun to dig in the family’s history.

Katrin could understand that it was difficult for her relatives and that they had to block out the association. She knew that the generation before her had had a much harder time dealing with what had happened. They could not stand it emotionally.

But Himmler’s grandniece kept on going

She met with an Israeli she knew from before. “Dani,” as Katrin Himmler calls him in her book, became her friend and then her husband. His father had survived as a boy in occupied Warsaw through the use of false “Aryan” papers. But she denies that she unconsciously sought a Jewish husband.

At some point, she joined her husband on a trip to visit his relatives in Israel. To her surprise, her last name did not matter because everyone called her by her first name. Even Katrin Himmler’s parents and parents-in-law got on well. They visited each other regularly, but they never talked about the past.

During a visit to Germany, her mother-in-law wanted to see the box with the old family photos. When she saw the image of the Reichsführer SS in full uniform, she put it aside. She did the same thing Katrin’s parents did; she wanted a normal family, so Heinrich was pushed aside.

Katrin Himmler only thought of changing her surname when she was a girl

Accepting her husband’s Jewish name was out of the question for Katrin in later years. She considers the name “Himmler” as part of her identity. However, she spared her son the name Himmler.

Telling her son about his family, their guilt and responsibility was the spark that made her write her book.

“I still am afraid of the moment when he learns that one side of his family was trying to eradicate the other side of his family,” she writes at the end of the book. “I’d like to postpone that as much as possible.”

When she started working on her German family history, Katrin Himmler had the hope that some of the burdens she carries would lessen, but that did not happen. They only became more concrete.

There were other moments, too, when her family’s history burdened her. Like, for example, when she discovered the testimony of Gebhard Himmler, Heinrich’s older brother, before the Nuremberg Trials.

Gebhard clearly attested that the Reichsführer SS had “deep kindness” and described him as a man who was “upright, simple and true to his path.”

“Personally, I would never see my brother as the culprit of those things,” Gebhard told the tribunal.

“It got really bad when I read that,” said Katrin Himmler during an interview. However, she never wavered and ultimately produced the book describing her family’s involvement with Heinrich Himmler.

Read another story from us: The Largely Overlooked Story of How Himmler “Saved” Thousands of Jews

Doug Johnstone wrote in The List magazine: “Katrin’s book is admirably level-headed, a meticulous memoir of an extraordinary family and the author never resorts to histrionics, preferring to let the facts speak for themselves. Originally written as self-therapy, the book stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of guilt the Nazis left behind for future generations.”