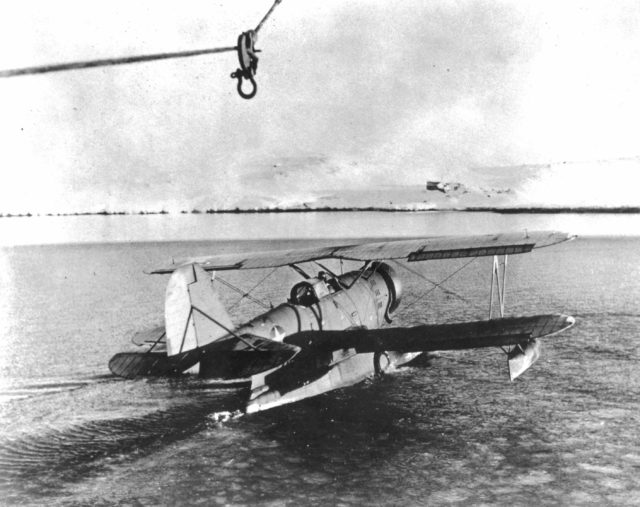

In August 2012, a team of explorers and U.S. Coast Guard Personnel found something amazing under Greenland’s ice. 38 feet down, sat a single-engined rescue float plane, preserved since 1942. The aircraft was a Grumman J2F-4 Duck, and onboard were three men, victims of Greenland’s harsh climate.

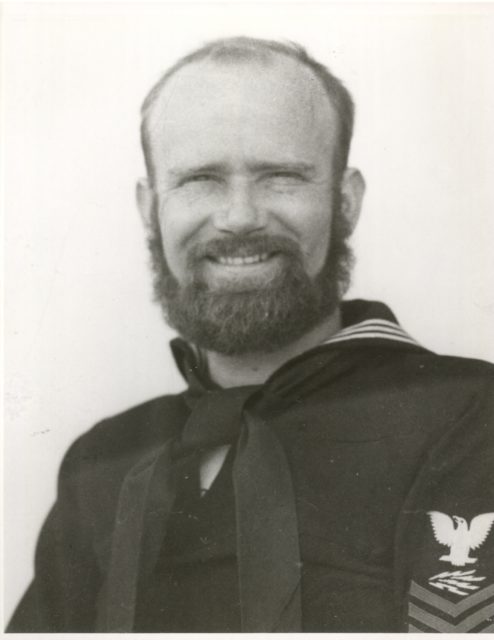

One of these men was Radioman 1/c Benjamin Bottoms, US Coast Guard. His was born in Marietta County, Georgia in 1913. He joined the Coast Guard in 1932, beginning his training in radio operations. By 1942 he was a Radioman 1st Class and received orders to report to the Coast Guard Cutter Northland, currently on the Greenland Patrol.

It was Bottoms duty was to relay information to and from the J2F-4 Duck carried by the Northland. The plane was sent on recovery and reconnaissance operations; searching for German submarines and saving sailors whose ships had been sunk. Bottoms was a vital link between the plane and the ship, guiding the Northland towards the survivors while still searching. He would accompany Lieutenant John A. Pritchard, the pilot, on every flight.

Pritchard, born in 1914, graduated from the Coast Guard Academy in 1938 and was assigned to the Northland shortly before Bottoms. Pritchard had experience in the Bering Sea and was a skilled aviator. With a passion for radio, he and Bottoms must have gotten on well, making the pair a formidable crew.

On November 23, 1942, the two set out in their small single engined floatplane, to rescue a group of Canadian aviators who had been stranded in ice for 13 days. It was Pritchard’s first rescue, a milestone in any Coast Guard career. For it, he was later awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

Five days later, Northland was sitting in Comanche Bay, on the western shores of Greenland. Suddenly a distress call came in from a B-17 bomber. They had been forced to crash land onto the ice cap, a treacherous situation in any weather. It was November, with high winds and low temperatures. Both Bottoms and Pritchard knew that time was of the essence if they were going to attempt a rescue.

Bottoms was able to maintain a weak connection to the bomber’s signal. This allowed them to get a rough bearing on its position. The two men decided the rescue was worth attempting. Their plane was lowered into the water, and they climbed on board. Little did they know they were about to embark on their last mission.

The engine sputtered and then burst into life. The hot exhaust must have been a nice relief for Pritchard as he sat with the cockpit open to the bitter cold. They taxied away from the cutter and took off. As the plane gained altitude Bottoms continually checked in with the downed B-17, trying to keep a steady bearing on its position.

Thanks to his radio expertise, they found the crash site with little issue. The American aircrew on the ground must have breathed a sigh of relief to see that small biplane pass overhead. The aviators warned the little plane not to land in the snowbanks with wheels down as they would get stuck. The snowdrifts in the area were several feet deep, and could easily swallow the undercarriage.

Pritchard heeded this warning and found a safer landing spot four miles away. He and Bottoms touched down safely. Someone needed to keep the ship updated on their position, and as radio contact from the ground was inconsistent at best, Bottoms stayed behind while Pritchard continued on foot.

Trudging through the thick snow and freezing wind the young Lieutenant made his way across the four miles to the crash site. There he told the bomber crew only two of them could come at a time. They all agreed that the two men who were wounded, but still able to walk, should be the first to go. Pritchard and another aviator escorted the wounded men back to the floatplane.

Bottoms was waiting for them and helped load the wounded men into the lower cabin. Bottoms, Pritchard, and the remaining Airman turned the J2F around, using the pontoons to take off from the ice, like a giant skate. The plane sputtered back to life, and as it gained speed, it bumped, scraped, and wobbled down the rough ice sheet. Finally, they had just enough power to get airborne, and headed back to Northland, with the promise they would be back for the other survivors. By the time they got back to the cutter, though, it was too late to attempt another rescue safely.

The next day, on the 29th, Pritchard and Bottoms set out again. Their small single engined plane had taken a beating the day before, but she could hold out for a few more flights. The J2F was a sturdy craft and had stood up to the arctic weather so far. In the morning they set out for their landing site again. Pritchard managed another successful ice landing. Again, he set out on foot, while Bottoms manned the radio.

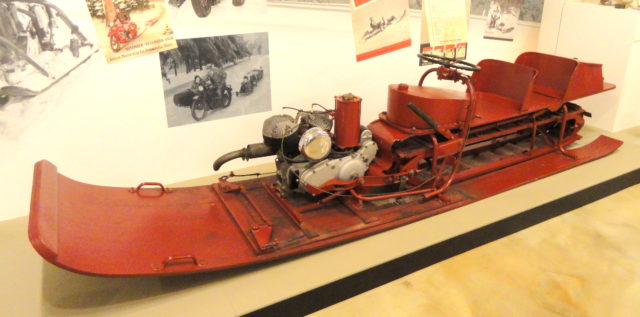

Unknown to the men at the time, a US Army Air Corps rescue party had set out at the same time. Riding motor sleds, they were approaching the crashed bomber, when disaster struck. An officer in their party had ridden over a hidden snow bridge, falling deep into the crevasse below, to his certain death. It was the first death Greenland would claim that day.

Pritchard found the crash site and discovered the US Army Air Corps motor sled rescue party. They told Pritchard about the lost officer. He decided he would return to Northland to collect more men and supplies for a concerted rescue effort. Heading back to the plane, he took a severely wounded man with him. Helping the survivor along, the two slowly made their way back to the float plane, and safety.

The weather was steadily getting worse. A dense fog had rolled in, dangerous flying in any conditions, but when surrounded by white mountains and ice cliffs, extremely tough. Pritchard, Bottoms, and the injured survivor from the crash took off. Again, skidding, bumping, and scraping along the ice sheet.

USCGC Northland continually asked for updates from their two crew members, miles away, and now surrounded by terrible weather. Bottoms reported back which must have warmed their hearts; their friends and shipmates were still alive. Then the transmissions grew faint. Finally, they lost contact altogether. That was the last anyone ever saw, or heard, of Radioman 1/c Benjamin Bottoms, or Lieutenant John Pritchard. The same day they were declared missing, and one year later, dead.

In 2009 a recovery effort began anew. Coast Guard members, along with North South Polar, began searching for the wreckage of USCG J2F-4 hull number v-1640.

After years of pouring over the charts and records from Northland, they identified a specific search area and began the pursuit in earnest. Finally, in 2012 they found it. 38 feet down, wiring consistent with the J2F-4 was located, roughly where the moving ice drifts would have dropped the plane, and her three passengers, after 70 years.

As per Title 10, United States Code, the remains must be brought back and properly interred. Over the past four years, recovery efforts have continued, but it is a slow and dangerous process. The ice sheet is full of hidden pockets and caverns, which could easily break open and swallow a research team.

Bottoms and Pritchard are without doubt Coast Guard heroes. They knew the high risk of their missions, but continued regardless, thinking more of saving a brother in arms, than of themselves. So too are the men and women of the rescue effort. Again, they are risking life and limb. This time to give closure and solace to the families whose loved ones disappeared so many years ago.

Semper Paratus.