By May 1945 the war in Europe had finally started to wind down. Yet for the men of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, there was one final mission to complete before they were relieved. Due to increasing tensions between them and the USSR, the Western Allies recognized that they had to take as much German territory as they could before the Soviets arrived.

They feared Communist expansion. Because of this, a small group of lightly armed Canadian paratroopers was tasked with taking the city of Wismar.

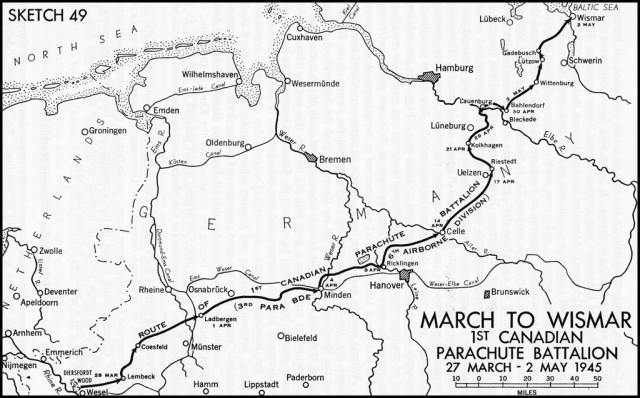

These Canadians, from the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, or 1CanPara, had been fighting almost nonstop since 6th June 1944. After jumping into Normandy, the men fought through the rest of the French Campaign. They were then used as support in the Battle of the Bulge. And in April 1945, were a part of the final Rhine crossing: Operation Varsity.

Shortly after Varsity that the unit got orders to march north to Wismar. Wismar is a city on the Baltic coast of Germany. It sits at the northern end of a chokepoint between the sea and Lake Schweringer and is a transportation hub. Winston Churchill recognized the city’s importance and knew that if it fell into Russian hands too quickly, it could allow them to advance far past the agreed upon lines set up at the Yalta conference and take most of Northern Germany and even Denmark.

Churchill was staunchly anti-communist and knew that the Soviets would never willingly give up territory they had taken. He needed a group of men who would be able to rush forward and stop their advance as soon as possible. Because of their excellent reputation, the men of 1CanPara were recognized as the best candidates for the job. They were attached to the British 6th Airborne Division and thus began a long march north.

This advance went quickly, and the men were surprised that they and their transports (sometimes tanks, sometimes trucks) would move past huge groups of German soldiers. Sergeant Andy Anderson described one such event: “The strangeness of the situation is that we are passing complete units of the Germany Army, lying by the roadside, some with vehicles, even horse-drawn artillery, but no shots are exchanged, no white flags were shown, and we cannot stop to disarm them.”

The men were understandably baffled by this experience, but orders were orders, and they kept going.

Finally, at 0900 2 May 1945, the battalion reached their destination. The residents of the city were relieved to have been liberated by the Canadians; they had heard the horror stories of Russian retribution and knew that they were far better off with 1CanPara.

The Battalion was pleased to be there as well; they could relax somewhat, and some of the men even went swimming in the Baltic Sea.

It was later in the day on 2 May when the battalion first came in contact with the Russians. Sergeant Nelson N. Macdonald was one of the first men to make contact when he and a section of about seven men went on patrol. The section found a Russian Sergeant driving a motorcycle with his Major in the sidecar.

The two men stopped, greeted the Canadians and exchanged rough pleasantries (there was no interpreter present). Shortly after that, the Russian Sergeant produced a bottle of vodka and glasses, and all the men toasted and drank. It’s shortly after this cordial meeting that the recorded history splits from what may have actually happened.

From speaking to veterans of the unit we’ve learned that a new war almost broke out over Wismar. They have explained to us that shortly after the initial contact with the Russians, Lieutenant-Colonel Eadie, Commanding Officer of 1CanPara, met with his Russian counterpart.

It was during this meeting that the Russian commander, backed by tanks, demanded a Canadian withdrawal, explaining that his objective was Lubeck, near Denmark. Lt.-Colonel Eadie, refusing to give in, told 1CanPara to prepare for combat. The Russian commander was taken aback; he knew no group of paratroopers would stand a chance against an armored unit.

Wrongfully assuming that the Canadians must have had airpower and armor of their own, he backed down, and discussions proceeded more diplomatically. The truth was that aside from the 6th Airborne Division’s artillery detachment the men in Wismar were almost completely unsupported by the rest of the Allied force.

While this small piece of history was never officially recorded, it has been confirmed by veterans of 1CanPara and the tensions caused by this brief encounter echoed throughout the rest of the discussions. Major Richard Hilborn, Commander of Headquarters Company, even noted that while 6th Airborne Division artillery was being prepped for transport back home, the Russians had begun to dig in and point their guns towards Wismar.

Tensions rose as the two armies settled in, and the Canadians soon realized why the Germans were so happy to have been liberated by them. There were numerous reports of Russian troops coming through the lines at night and raping or killing the civilians in the town. This was a persistent problem, and there didn’t seem to be any effective solution to it.

While it is unconfirmed by other sources, Lance Sergeant Feduck of 1CanPara claimed that the incidents stopped after a few Russians were shot and killed. He doesn’t specify who killed them though, and it’s unlikely that it was a Canadian, as that would likely have been the final straw which unleashed the Soviet military onto Wismar.

While 1CanPara tried to protect the citizens of Wismar; talks continued between East and West. After breaking down between Lt.-Colonel Eadie and his Russian counterpart, they moved up the chain of command. The Russian General was communicating with Major General Bols, of the British 6th Airborne Division and demanded, again, that the Canadians leave the city.

Bols, like Eadie, was faced with a massive contingent of Russian armor but did not back down. He explained that his men were already in possession of the city, and were determined to stay there. Bols’ refusal to move forced the negotiations to drag on again and eventually they moved up the chain to Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery and Soviet Marshall Rokossovsky.

Unfortunately for the people of Wismar, Montgomery was less confrontational than Bols or Eadie were and took a more political approach. He defaulted back to the lines drawn up at the Yalta conference of 1944. This agreement put Wismar squarely into Russian hands and, by July 1945, the Allied forces had retreated west, and the Russians moved in.

While negotiations eventually ended with the Russians holding the city, it must be understood that the Canadians, by taking it early, and holding it for as long as they did, still served a very important purpose. Taking the city before the Russians prevented them from moving past it. Had they been allowed to advance freely to Lubeck they could very easily have gone north into Denmark.

It also allowed many former German soldiers and civilians to flee from Russian reprisals and terror. Lt.-Colonel Eadie’s and General Bols’ refusal to back down forced the negotiations to last longer and bought time for many of the innocents in the area to escape west.

The taking of Wismar is a little-known sideshow from the end of the Second World War, but its consequences likely saved untold numbers of lives. These small events and individual stories are what makeup history, even if they’re not officially recorded, and by looking into them; we can get a much deeper understanding of it.

While it may not have been terribly glamorous or well recognized, the men of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion were proud to have been part of this mission, and there are likely many people alive today because of their willingness and ability to do what had to be done.