When America entered WWII, one of the first orders of business was to find ways to work with the British. With their shared language and purpose, the two nations had a better chance of cooperating than almost anyone in the world.

However, cooperation often proved difficult. When it came to sharing high-level military intelligence, several obstacles stood in the way.

A Personality Clash

From the moment they began working together, the different cultures and experiences of their armed forces came into play.

The British had a long tradition of military professionalism. They had been a global power since the 16th century. Between the fall of Napoleon and the outbreak of WWI, they were arguably the most powerful nation in the world. They had colonies scattered across the globe and a navy that was second to none.

The British had been in the war from the start. They had gone through the disillusionment of the fall of France, the grim bombardment of the blitz, and many months as the sole bastion of light against the darkness of Nazi Germany. They felt they had an edge due to their recent experiences as well as professionalism.

America, on the other hand, was coming into its own as a global power. Its vast resources gave them the confidence to throw their weight around. Their soldiers had been well trained for war, even if they had not yet seen action. They were more expressive than the British, who they found stand-offish.

Each side tended to find the other rude and arrogant, either because of their coldness or their brashness. In North Africa, it resulted in fist fights between soldiers in bars and rivalry between generals who should have been cooperating. In the field of intelligence, it made it hard to work together.

Keeping Ultra Safe

Trust and professionalism were especially important to British intelligence because of one project; Ultra.

At the start of the war, Polish intelligence had been working on decrypting Enigma, the German cipher used for top-level information. When their country fell, the Poles brought that work to Britain.

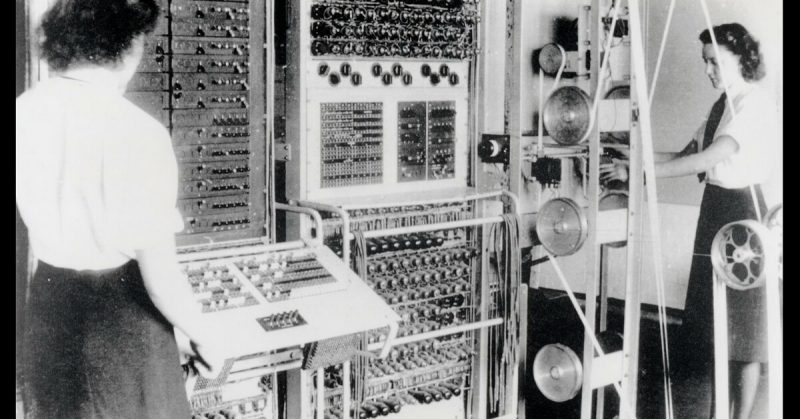

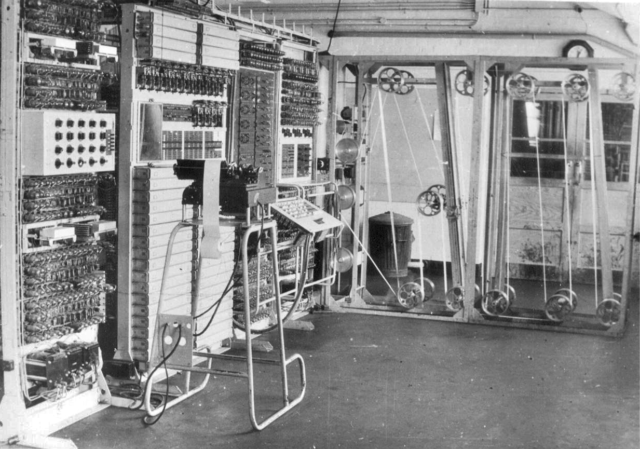

What followed was one of the greatest achievements in the history of military intelligence. Building on the Polish work, the British cracked the Enigma code. It enabled them to read messages passed between Germans at the highest level of command. It gave insights into their strategy, supplies, and troop movements that were not available in any other way.

It was incredibly valuable – but only while the Germans did not know about it. If the Nazis realized their cipher had been cracked, they would change it. All progress would be lost.

To prevent that happening, the British were incredibly careful with Ultra. Its information was passed to only a handful of supreme commanders. They were not allowed to share where the information came from or in many cases what it was. During the defense of Crete, General Freyberg was told he could not act on anything that came solely from Ultra, no matter what its value might be.

Sharing top intelligence with the Americans meant expanding the circle who knew about Ultra. It involved taking control of any information out of British hands. Given Ultra’s ongoing value, they were reticent to do so.

Washington Politics

While half-justified paranoia held back cooperation on the British side, the American military was making a rod for its own back.

An inter-departmental rivalry is the bane of any large organization. In Washington, it was exemplified by power struggles between the Navy and War Departments. The bitter tussle made it awkward for the British to cooperate with their trans-Atlantic cousins, as the Americans were not working together themselves. An initial agreement to share information about U-boats in the Atlantic did not expand into greater cooperation because of the disruption that rivalry caused.

There was also a matter of American pride. Its military wanted to set up its own equivalent of Ultra which would give them greater control over the information and higher status.

That prospect was shot down in April 1943, when the first American delegation visited the British decryption center at Bletchley Park. The head of the delegation telegraphed his colleagues in the US, saying they would have to learn about the work from the British as they “never on God’s green earth” would work it out for themselves.

Suspicious Minds

It was natural for intelligence staff to be suspicious. Unable to explain themselves to each other, suspicions flourished between the two sides.

The Americans held the deepest concerns following events from February to December 1942.

In February, German U-boats in the Atlantic completed their shift from a three-rotor Enigma machine to a four-rotor one. Suddenly, their signals were incomprehensible. The British had no four-rotor decryption devices with which even to try breaking the code.

That blow fell as trans-Atlantic convoys from America increased. Just as U-boat information was at its most vital, it dried up. The British could tell their Allies there was less information to share, but without telling them about Ultra, they could not explain why.

In October 1942, the Royal Navy sank U-559. As the U-boat went down, sailors retrieved its codebooks and four-rotor Enigma machine. Two of them died in the process. In mid-December, the code had been cracked. The flow of intelligence about U-boats began again.

The Americans did not know what was going on. Instead, they suspected the ten-month Ultra black-out represented a cover-up. Suspicions rose.

The two sides eventually managed to cooperate. The visit to Bletchley Park in April 1943, was a significant concession from the British and convinced the Americans they needed to work with their allies on top-level intelligence. By the time D-Day came, there were as many Americans as British working on Ultra.

Two intelligence services divided by a shared language had learned to work together.

Source:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945

Nigel Cawthorne (2004), Turning the Tide: Decisive Battles of the Second World War