In the small Karen village of Mewado, Burma, two men stood smoking cigarettes. The owner of the cigarettes, Captain Inoue, was an officer in the Kempeitai, Japan’s feared military police. His companion was the man he had been hunting, a British officer named Hugh Seagrim.

Seagrim finished his cigarette and refused the offer of a whole packet. For him, this was the end of a two-year campaign of guerrilla warfare. He faced it as he did everything; undaunted by what the world threw at him.

An Indian Sort of British Officer

The British army of the late 1920s was entrenched in deep divides of class and wealth. For a young officer without much money, the best way to advance his career was to serve far from home in the Indian Army.

This was what happened to Hugh Seagrim. Born in 1909 and privately educated until his father died in 1927, he was suddenly short of financial support. After officer training at Sandhurst, in 1929 he was posted to India, where he spent a year in Cawnpore before joining the Burma Rifles.

Intelligent, widely read, and a gifted linguist, Seagrim excelled in his role. His humility and humor made him popular with his peers.

Life Among the Karens

Predominantly of Christian religion, the Karens were a Burmese ethnic minority who had often suffered from oppression. Most lived quietly in rural villages led by tribal elders. Many of them served in the Burma Rifles, a British colonial unit raised and based in the region.

Seagrim’s good character, Christian faith, ability to speak their language and soccer skills made him popular with the Karens.

Preparing for Resistance

In 1941, the Japanese launched a string of offensives against American, British, and Dutch territory in South-East Asia. With their superior numbers and air support, they made swift advances.

As they were forced back in Burma, the British tried to resist the Japanese. Operation Oriental Mission was set up to delay the Japanese by using irregular forces.

Seagrim had long argued that the Karens, once cut loose from traditional training drills, would make excellent guerrilla fighters. To his delight, he was recruited into Oriental Mission. He was to organize stay-behind units, waiting for the Japanese to pass and then attacking their supply lines.

Cut Off but Persisting

In January 1942, Seagrim headed into the mountainous Papun region. He had a few hundred rifles and a few thousand rounds of ammunition. Almost immediately, he was completely cut off from supply and communication with the regular British forces.

Starting with 200 new recruits, he formed a resistance force. He abandoned traditional fighting methods instead using concealment, ambush, and sharp shooting. The Karens made use of the country they knew so well.

Cheerful, despite the constant danger of capture, and dressed in native clothes, Seagrim moved around Papun. He recruited more men, resorting to Karen crossbows when they ran out of guns.

Building a Secret Army

After being wounded in an ambush, Seagrim was tended back to health by the Karens. By now, Oriental Mission was a holding action only, but he never lost faith.

Traveling around a vast territory, Seagrim kept up Karen morale. He sought out veterans of the Burma Rifles, assembling a list of potential fighters and making plans for the British return.

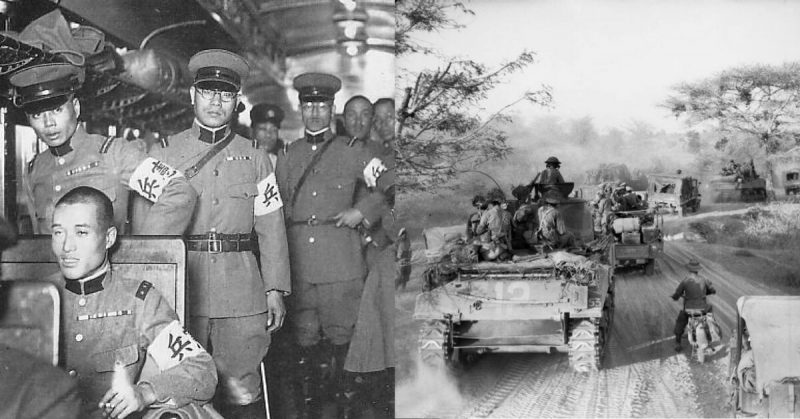

The Japanese Start Their Hunt

In October 1943, the British finally managed to contact Seagrim. They were now on the offensive and preparing to stir trouble behind Japanese lines.

The parachute drops that had brought more British agents into the region caught the attention of the Japanese. An undercover military unit started asking questions. It confirmed to the Japanese that the British were active in the area. It also showed Seagrim he was hunted and he withdrew higher into the hills.

The Net Tightens

Japanese soldiers and agents poured in, to hunt Seagrim. They tortured his contacts for information and destroyed innocent villages in a reign of terror meant to drive him into the open.

At one point, a Kempeitai unit led by Captain Inoue almost captured Seagrim at one of his camps. Afterward, they found his copy of the Bible among the abandoned possessions.

Surrender

Inevitably, Inoue closed in on Seagrim in his new hiding place near the village of Mewado. The people of Mewado had been sheltering Seagrim and Inoue threatened to burn the village down unless the Englishman surrendered.

Having rejected suicide as an un-Christian option, Seagrim decided to surrender. He handed his watch to the village headman, asking him to send it to his mother after the war. Then he handed himself in.

It Was All Me

After their initial greeting and cigarette, Seagrim and Inoue spent several days in Mewado, talking through an interpreter. They talked about Seagrim’s plans to be a missionary among the Karens after the war. Inoue returned his Bible to him.

On March 16, 1944, Seagrim was taken from Papun. He spent months in a Japanese jail, keeping up the spirits of other prisoners through his humor, courage, and displays of Christian faith.

On September 2, a court-martial was held against Seagrim and fifteen Karens. When talking with Inoue at Mewado, Seagrim had pleaded for clemency for the Karens, saying that their defiance of the Japanese was his doing and that he alone should be punished.

Seagrim and seven Karens were sentenced to death. As he was taken away to die, he smiled and waved goodbye to those who had been allowed to live.

A Legacy of Resistance

Hugh Seagrim was honored with a posthumous George Cross for courage and self-sacrifice.

In April 1945, more than 12,000 Karens rose against the Japanese. Their successful campaign of irregular warfare was a tremendous support to the advancing British and helped bring about the surrender of the Japanese in Burma in May. It was made possible by Hugh Seagrim’s courage and tenacity in the face of terrible odds.

Source:

Gordon Brown (2008), Wartime Courage.