Codenamed Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa was the largest amphibious landing in the Pacific theater of the Second World War which started on April 1st, 1945.

In Spring 1945, Allied forces were advancing on Japan, and Allied planes were able to bombard her cities. Okinawa, a 70-mile long island 350 miles from Japan, was seen as the final step before a full-scale invasion of the Japanese Homeland.

Invading Okinawa

120,000 Japanese troops under General Mitsuru Ushijima stood ready to defend Okinawa, though the Allies believed there were only half that many. They were supported by 10,000 aircraft and a naval force led by the largest battleship ever built, the Yamato.

Against them came 155,000 American troops, consisting of Marines and infantry, though twice this number would be involved before the end. They were led by Lieutenant-General Simon Bolivar Buckner and supported by 1,300 ships, including a large British carrier group.

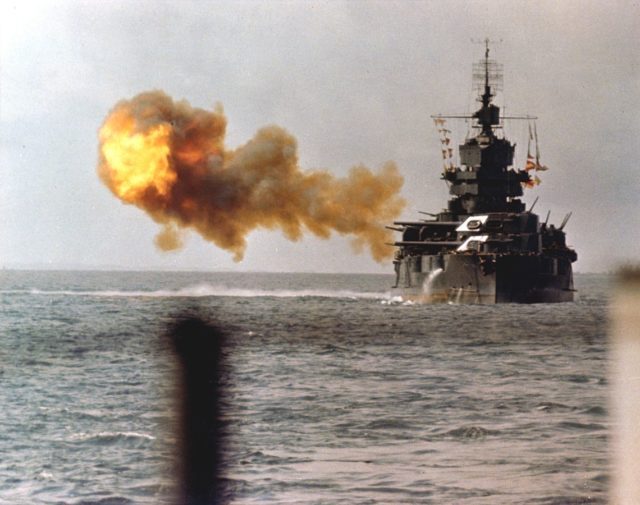

From October 1944 to March 1945 the Americans launched air raids against Okinawa, destroying hundreds of enemy aircraft. A naval bombardment was added from 18 March, despite kamikaze pilot attacks that damaged four aircraft carriers and took out two ships.

Meanwhile, ground forces took outlying islands, including the forward base for the operation, the Kerama Islands.

On 1 April, the day of the invasion, a devastating bombardment fell on the island – 44,825 shells, 22,500 mortar rounds, and 32,000 rockets. The approach to the island had been cleared of mines, and the troops were ready to go.

At 4 am the landing craft set off in the waters west of Okinawa, heading for Hagushi beach. Four and a half hours later they reached land as planned, ready for a desperate fight to establishing a beachhead. If they could not seize a beachhead, then the invasion could fail. But no-one stood in their way – the Japanese, adopting a new tactic would make their stand further inland.

By the time darkness fell on 1 April, the Americans held an eight-mile wide beachhead with 60,000 men.

The Struggle for the Island

The seemingly ‘easy’ invasion to continue into the next day. American soldiers crossed the width of the island, dividing the Japanese in two. Two airfields were captured, an important step given the kamikaze attacks on US ships.

The 6th Marine Division was sent north. They entered into a trap set by the Japanese. Three weeks of fighting saw them lose 218 dead and 902 wounded. In that time, they killed 2,500 Japanese troops and secured the northern half of the island. By then Buckner already knew where the real fighting would be – General Ushijima was defending the south.

Ushijima could not win, but he wanted to keep the Americans tied down with a war of attrition. On 4 April, the US 24th Corps met the beginnings of this resistance at the city of Shuri.

On 6 April the kamikaze flights resumed. 700 planes hit the 5th fleet, destroying or damaging 13 destroyers. These were followed just over a week later by a new suicide weapon, the baka. A rocket-powered glider with a ton of explosives in the nose, the baka was towed by a bomber until it reached strike range. Gliding to three miles out, the pilot would ignite the rocket engines and dive on the target at speeds above 600 miles per hour. The explosions of these devices destroyed not only the gliders and their pilots but, in a short period of time. some 34 Allied ships.

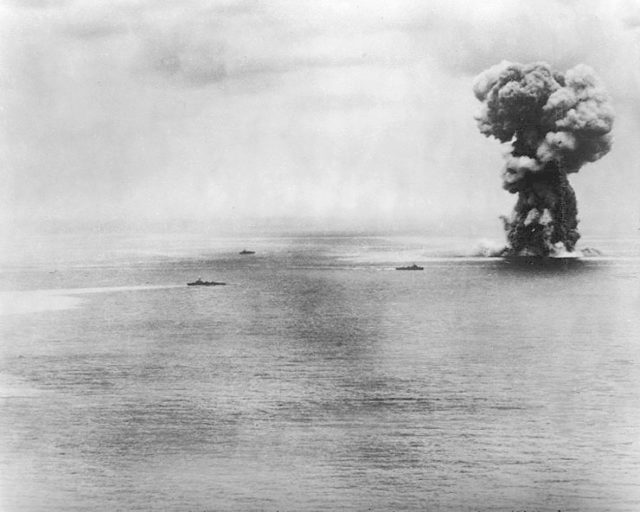

The Japanese fleet also undertook a suicide mission. Using what little fuel remained, the Yamato, the cruiser Yahagi and eight destroyers headed for Okinawa, where they intended to beach themselves, adding their guns to the firepower of the defenders. But they were spotted on the way. Lacking air cover, they were easy targets for the American flyers. The Yamato, the Yahagi and four destroyers were sunk.

On land, the Americans were struggling against Ushijima’s defenses. Though they were killing ten times as many soldiers as they were losing, they could make little progress against the determined and dug in Japanese.

Despite his own horrifying casualties, Ushijima went on the offensive on 12 April, sending waves of men against the Americans in attacks almost as suicidal as those occurring at sea. Every assault was driven back by the Americans, and after two days the Japanese returned to defending.

Fighting to the Bitter End

Buckner ordered greater bombardments and a renewed offensive, but the Marines could not break through the well-prepared Japanese defenses. Rather recklessly, Ushijima ordered another offensive on 2 May, in which he lost 5,000 troops.

A change in American tactics came on 11 May when Buckner ordered attacks to be focused on the Japanese flanks. This began to work and, rather than become surrounded, Ushijima pulled back on 21 May. A rearguard fought fiercely, holding onto Shuri until 31 May. Meanwhile, the rest of the Japanese made an orderly retreat to the southern tip of Okinawa and their last stand.

The fanatical fighting of the Japanese made American advances horribly slow, but they still advanced. High explosives and flamethrowers destroyed defensive positions as the Americans crawled south. The 6th Marines landed on the Oroku Peninsula in the southwest, providing an airfield and strongpoint for the Americans in the south.

General Buckner was fatally wounded 18 June. He was soon followed by his opposite number. On 21 June, Ushijima and his chief of staff committed hara-kiri outside their headquarters rather than lose or surrender.

Following their general’s final order, the Japanese continued a guerrilla war against the invaders until the end of June. When 7,400 men gave in, it was the first large surrender of Japanese soldiers in the entire war.

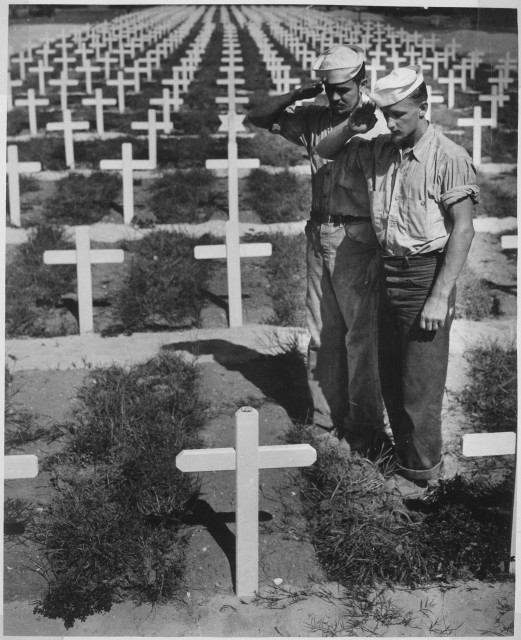

Okinawa was a bloodbath for the Japanese, with 110,000 soldiers and an unknown number of civilians dying. The Americans lost over 12,000 dead – 5,000 of them at sea – and 37,000 wounded. The Japanese navy was annihilated, along with thousands of planes. The way to Japan now lay open, and though it had cost the Allies dearly, it had cost their enemies far more.