In times of war, it’s not only soldiers who perform feats of great valor and display incredible courage. Oftentimes, non-combatant civilians risk their lives by performing quiet, yet extraordinary acts of selflessness and gallantry that require just as much bravery as troops charging head-on into enemy fire.

Irena Sendler was one such civilian. She was a gentle, but determined Polish social worker who managed, with the help of a group of volunteers, to smuggle 2,500 children out of the Warsaw Ghetto during the Second World War. As amazing as this feat was, she was only internationally honored for her immense bravery toward the end of her life.

Irena Sendler’s father was devoted to doing good

Irena Sendler was born in 1910 in Warsaw, Poland. Her father’s dedication to doing the right thing, regardless of the risk, must have certainly made an impression on her when she was young, despite the tragic consequences of his unshakable devotion for good; in 1917, he died from typhus, having contracted it while treating patients other doctors refused to care for.

Many of his former patients were Jewish, and in gratitude for what he’d done for them, community leaders sponsored his daughter’s education.

German invasion of Poland

When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Irena Sendler immediately began to help local Jews by offering them food and shelter. However, once the Germans had established the Warsaw Ghetto, it became much more difficult for her to provide help.

On November 16, 1940, the Warsaw Ghetto was completely sealed off from the rest of the city. Sendler realized she’d have to adopt an alternative – and more covert – approach to helping those in need.

Horrible conditions within the Warsaw Ghetto

Surrounding the Warsaw Ghetto was a 10-feet-high concrete wall topped with barbed wire and broken glass. All access points were heavily guarded by Germans troops. Getting in, as an ordinary Polish citizen, would have been nearly impossible.

Despite this, Irena Sendler knew she had to help. Conditions for the nearly 400,000 Jews crammed into the ghetto were horrific. As a result of severe overcrowding, a lack of sanitation and miserly rations (only 200 calories per day), starvation and disease ran rampant.

Irena Sendler goes from social worker to nurse (on paper)

Realizing her identification documents, which stated she was a social worker, were insufficient to obtain access to the Warsaw Ghetto, Irena Sendler obtained fake ones identifying her as a nurse. This allowed her to get in and out of the area.

To begin with, Sendler smuggled in medicine, food and clothes. The risks associated with something seemingly so innocuous were, in fact, substantial. From October 1941, the Germans stated that helping Jews was a serious crime – one punishable by death.

However, this didn’t stop Sendler. She courageously continued smuggling food and medicine to the residents of the ghetto. She also forged paperwork to help them.

Irena Sendler joins the underground Resistance movement

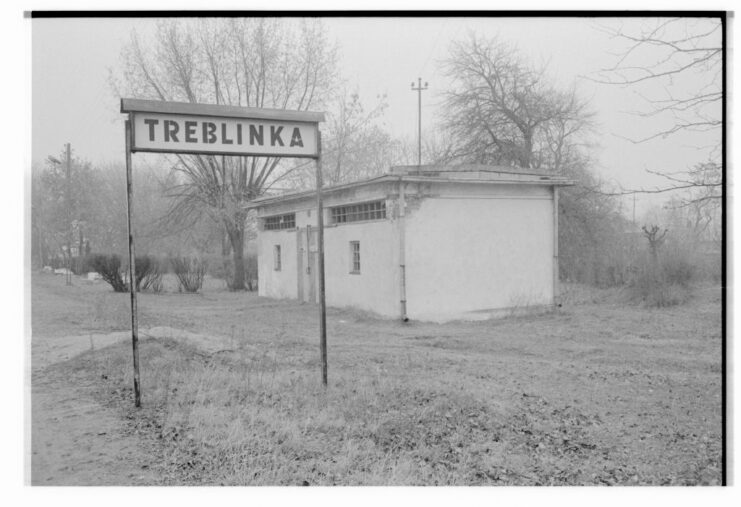

In 1942, when the German military began deporting Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto to the notorious Treblinka extermination camp, it became clear to Irena Sendler that time was running out – she’d need to take more drastic measures to help.

Sendler joined the newly-formed underground Resistance organization, Żegota, and soon became the head of its children’s unit. This was when her most dangerous and difficult work began. Desperate times called for desperate measures, and Sendler vowed to do whatever it took to save as many children as she could from being sent to Treblinka.

Saving children from being sent to Treblinka

Irena Sendler and a group of volunteers began the extremely risky task of smuggling Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto. Because of the extreme danger involved in what they were doing, they came up with a number of inventive ways of smuggling them out. These ranged from sending them through underground tunnels to physically carrying them out. This involved hiding them in suitcases, boxes and even coffins.

When it came to smuggling out babies, whose cries could attract the attention of guards, Sendler and the others used sedation, to make sure the infants stayed quiet. In this way, Sendler and her group were able to rescue an astonishing number of kids: almost 2,500.

The rescued children were taken to Roman Catholic orphanages and convents (even private homes) and given non-Jewish names, to keep their true identities safe from the Germans. Sendler recorded the name of each child she saved, along with the names of their parents and relatives. She wrote these details on scraps of paper that she then put in jars, which were then secretly buried in a friend’s backyard.

Sendler hoped that, by preserving these details, she could reunite the children with their families after World War II had come to an end.

Irena Sendler is arrested by the Germans

The Germans soon became aware that someone was smuggling children out of the Warsaw Ghetto. They arrested Irena Sendler in October 1943. She was brutally tortured during interrogation sessions, with both of her feet and legs being broken, yet she refused to betray her friends in Żegota and didn’t give up any information.

Sendler was sentenced to death, but, on the day of her execution, the Gestapo officer charged with ending her life informed her that her friends in Żegota had successfully bribed him to spare her life. He secretly released her and added her name to a list of executed prisoners.

After this, Sendler went hiding and stayed underground. Even while in hiding, however, she continued to help the Resistance in whatever way she could.

How was Irena Sendler honored for her bravery?

After the Second World War, Irena Sendler returned to her friend’s backyard to dig up the jars she’d buried, hoping to reunite the children she’d rescued with their parents and families. Unfortunately, by that time, almost all of their families had been executed in the death camps. The rescued children were thus either adopted by Polish families or sent to Israel.

Despite Sendler’s incredible courage, selflessness, tenacity and the remarkable fact she’d risked her life day in and day out for years, her heroic actions went unrecognized for most of her life, and she remained a little-known figure outside of Poland. She finally received the recognition she deserved (but never asked for) in 1999, when students in Kansas produced a play, Life In A Jar, based on her exploits in Warsaw.

More from us: George Ray Tweed: The Man Who Evaded the Japanese on Guam for Over Two Years

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

After this, Sendler’s story became known around the world, and she was presented with a number of international awards. She passed away in May 2008, at the age of 98.