George “Joe” Taro Sakato is a second-generation-born American of Japanese descent, which was why his family had to relocate during WWII. Despite this, he joined the US military which was how he helped to save a battalion of Texans. This earned him the Medal of Honor – America’s highest military award for valor.

It all started when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Besides racism against Asians, that attack gave many an excuse to eliminate competition from Japanese-American farmers and businessmen, especially on the West Coast.

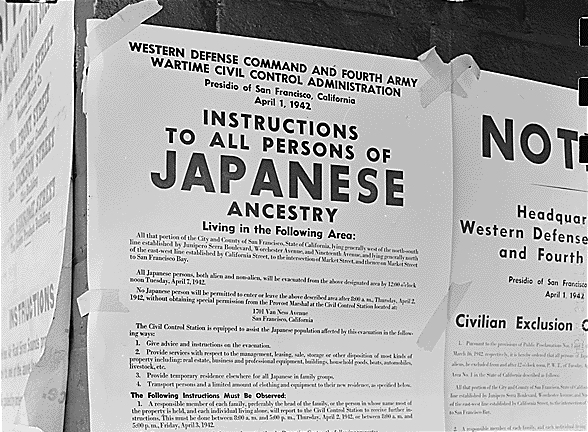

Calls were made to expel or incarcerate all Japanese on US soil, even those who were American citizens. Since Japanese-Americans were quite populous in some states, however (especially Hawaii), not all agreed, so the policy didn’t become nationwide.

Sakato was born in Colton, California in 1921, so his family had a choice – leave or go to a camp. They moved to Arizona. Even though that state also called for the expulsion of all Japanese, it did set up government camps where they could live under military supervision.

With the mood in America fiercely anti-German and anti-Japanese, nowhere was safe for them. While those of German descent could blend in, the Sakato’s could not. By living in a camp, they could, at least, avoid being lynched or worse.

Even the Japanese who served in the National Guard and the military fell under suspicion and were discharged. As the US had entered the war, however, this was not practical, so those who were part of the Hawaii Territorial Guard were reformed into the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate).

They did so well in training that the government decided to expand their numbers. But first they had to pass a loyalty test. They were asked if they would serve the US wherever they were sent to and if they would forswear any loyalties to the Japanese emperor.

Since all were second and third generation born, they were offended by these questions. They knew no other home and felt no loyalty to any other government. Some protested the camps while others refused to answer. These were imprisoned on the charge of “evading the draft.”

About 75% said “yes” to both questions, however, and were allowed to serve – but never in the Pacific. In 1944, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) was created, also made up of Japanese-Americans. In March of that year, Sakato joined them.

The 442nd got reunited with the 100th on 26 June 1944 when they liberated the Italian town of Belvedere. By July 1, the 442nd took Cecina and later took part in the Southern France Campaign from August 15 to September 14, earning their second Presidential Unit Citation.

By September 30, they were in the Rhone Valley making their way toward the hill town of Bruyères in northeastern France. Hitler had given a no-retreat no-surrender order since the German border was the next stop. After being joined by several other Allied battalions, Bruyères was finally taken on October 20.

The 442nd and the 100th were then sent to Biffontaine. Before they got there, however, the former were ordered east. It was there in the Vosges Mountains that Sakato entered history.

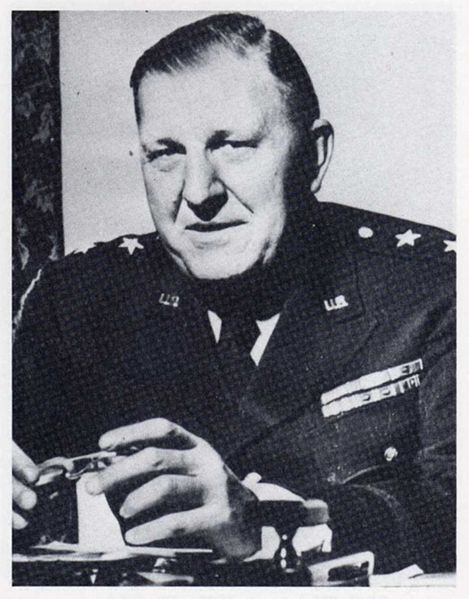

It all began when the Texas National Guard became the 141st Infantry Division under Major General John E. Dahlquist. His superiors thought it a bad idea to try breaking through the German defenses, but Dahlquist thought otherwise, so he ordered his men to attack on October 24.

As a result, the “Texas Battalion” was trapped by the German 244th and 716th Infantry Divisions. The US 36th Division sent two battalions to rescue them, but failed, so the 405th Fighter Squadron had to airdrop supplies to the 275 trapped men who were collectively called the “Lost Battalion.”

They were so lost, in fact, that even the Germans didn’t realize they had trapped an entire unit. They only found out when the aerial resupply began, since some of the supplies fell among them (a welcome respite since they were running low on supplies).

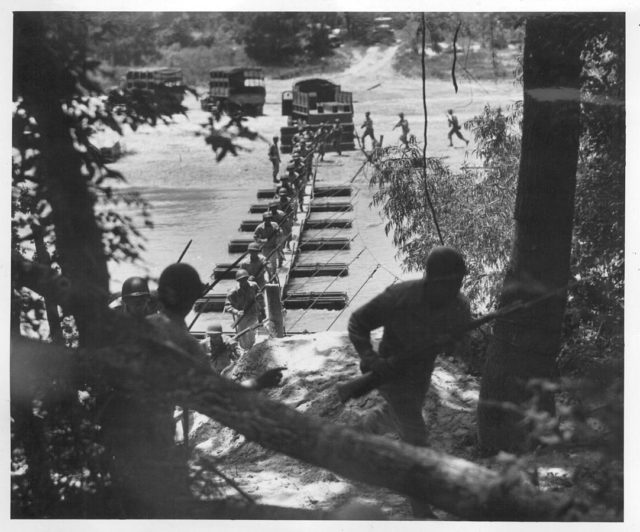

The 442nd arrived on October 27 at 4 AM. With support from the 522nd and the 133rd Field Artillery units, they began their attack, but couldn’t penetrate the German line. Things were made worse by the dense fog and very dark nights that limited visibility and prevented further resupply flights from coming through.

The 442nd continued into the German line of fire, knowing they were being used as cannon fodder (and for which Dahlquist would later be criticized for). By October 29, Sakato’s group managed to clear a German strongpoint, but no sooner had they done that than German artillery began firing at them.

He jumped into the ditch and was joined by Private Saburo Tanamachi, an old friend from Arizona who had been interred with his family. While the bombardment continued, the two got reacquainted, desperately trying to block out the horrors around them. They’d been together at Bruyères, but hadn’t had a chance to talk.

In a 2011 interview with Densho Oral History, Sakato explained how magical that reunion was. It not only reminded him of home, but it also reminded him of how things were like before their expulsions began. But as they talked, some Germans reached the hill above them.

Sakato noticed and yelled, “Watch out! They’ve taken the hill back!”

Tanamachi stood up, “Where!?”

And got shot through the neck.

“Why the hell did you do that!?” Sakato raged as he cradled the man in his arms. “Why!?”

Tanamachi tried to reply, but blood came out of his mouth before he went still.

Sakato continued to rage at his friend until incoming fire brought him back to reality. Grabbing a Thompson submachine gun, he ran up the hill in zigzags as a group of Germans continued to fire back at him. They all missed.

Sakato, on the other hand, killed five Germans, forcing the remaining four to surrender. While his platoon was reorganizing, he proved to be the inspiration of his squad in halting a counter-attack on the left flank during which his squad leader was killed. Taking charge of the squad, he continued his relentless tactics, using an enemy rifle and P-38 pistol to stop an organized enemy attack.

In the aftermath, 34 Germans surrendered, while 211 Texans were rescued at the cost of over 800 Japanese-American casualties.

Texas only repealed the Jim Crow laws in 1964, ending the rest of its separatist statutes in 1969. Despite this, the surviving members of the 442nd, including Sakato, were made “honorary Texans” in 1962.

Sakato was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross on 29 October 1944, but it was upgraded to the Medal of Honor on 21 June 2000.