Two planes fielded by the Japanese late in the Second World War, the Kawanishi N1K1-J and N1K2-J fighters, became popular with the Japanese military, despite having an unusual development history.

In the history of aircraft design, it hasn’t been that unusual for land-based planes to be converted into seaplanes. It’s a natural step from the more familiar role to a somewhat more unusual one, removing wheels, adding floats, and making other adaptations.

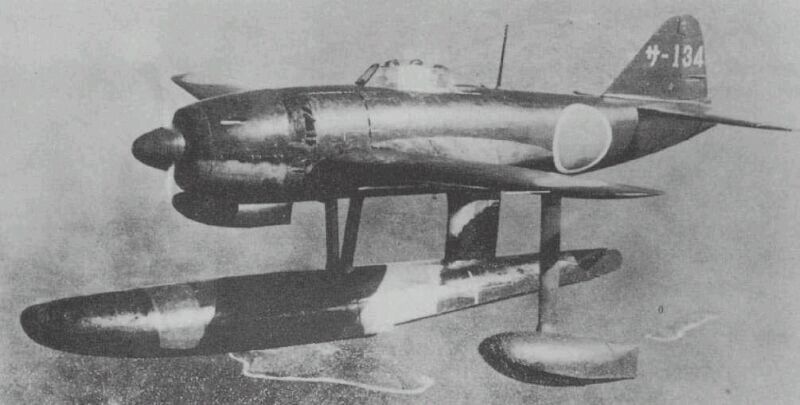

For the Kawanishi N1K1-J, however, the pattern was the other way around. The N1K1-J Kyofu (meaning “mighty wind”) was a seaplane fighter. It was successful enough to be adapted into the land-based N1K1-J Shiden (meaning “violet lightning”).

Production Problems

By the time the N1K1-J Shiden went into production, the tide of war had already turned against Japan. The Allies, particularly the Americans, were pushing them back across the Pacific, island by island. On the mainland, the Chinese kept fighting with the help of international support, while the British pushed back in Burma. As the sphere of Japanese control shrank, so did the safe territory that the nation’s factories could operate in.

The result was production problems for the N1K1-J. Raids by Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers on factories on the Japanese mainland added to existing difficulties of supply and production.

The N1K1-J Shiden came into service late in the war. It started to be fielded across the Pacific theatre in May 1944. Despite the production problems, large numbers of N1K1-J Shidens were produced – over 1,400 by the end of the war.

The titles given to these fighters by their creators were full of dignity and drama. The codename given to them by the Allies was less so. The Japanese used “Mighty wind” and “Violet Lightning” whereas the Allied forces referred to the planes by the codename “George”, a Christian name common in England at the time.

Deadly Maneuvers but Altitude Deficiencies and Design Flaws

One of the most successful features of the plane was its automatic combat flaps. This unique feature helped pilots to make extreme combat maneuvers by giving them extra lift. This made it one of the most successful all-round fighters in the Pacific theater, able to take on fighters and bombers alike.

The N1K1-J Shiden’s biggest downside was that it perform well at high altitudes. This was a problem for the Japanese air force, as they faced, the most powerful bombers of the war. The B-29 could reach an altitude of nearly 32,000 feet for bombing runs on Japan, and from the end of 1943, the Americans decided not to use any other bombers in their raids against the Japanese. Any Japanese plane that couldn’t perform well at high altitude would struggle to defend the homeland.

Early models of the Shiden had further problems. The mid-mounted wing produced poor visibility, a serious problem for pilots caught up in dogfights. The landing gear, the most important change from the seaplane version, was also inadequate. Changes needed to be made.

Enter the N1K2-J

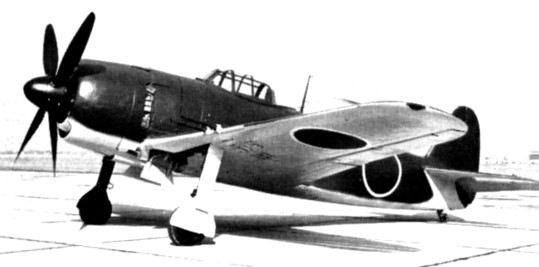

The result was a new model, the N1K2-J Shiden-Kai. The prototype for this version first flew at the end of December 1943 and it was soon rushed into mass production.

The N1K2-J was so successful that it soon became the standard land-based fighter and fighter-bomber of the Japanese military. It could hold its own in combat against almost anything the Allies threw against it. Though the tide of war was against them, Japanese fighter pilots at least had an edge in the skies.

The N1K2-J wasn’t just better because of its superior flying abilities. As with several of the best weapons in history, its advantage also came from being easy to produce. An N1K2-J could be completed in half the time it took to build one of its predecessors. With the losses mounting and the pressure on, this was a vital feature for the Japanese.

Mixed Armament for More Versatility

The N1K2-J was equipped with a mix of weaponry – in the wings were four 20mm cannons, while a pair of 550lb bombs were fixed underneath. This allowed the plane to act in a support role, not just as an interceptor. It could use its cannons in the skies against other planes, or to strafe enemy infantry and ships, which were also the targets for the bombs.

The presence of cannons rather than machine-guns was important. In the early war, many fighters on both sides had relied on machine-guns. But the experience of combat had taught the military that bullets were not enough to take out the latest planes and that cannons firing explosive rounds would be needed instead.

Fast But Not Fastest

The N1K2-J had a maximum speed of 370mph and a rate of climb of 3,300 feet per minute. This put it on a par with the Spitfires and Messerschmitts doing much of the fighting in Europe. It also made it superior to the Grumman F4F Wildcat, a fighter widely used by the Americans in the Pacific.

It was, however, slightly out-matched for speed and climb by Grumman’s major late-war plane, the F6F Hellcat. The Shiden-Kai was a good enough plane to compete with its main adversaries, but American industry still held the edge.

Kamikaze Flights

Despite its superiority in the air, some N1K2-Js were deliberately crashed by their pilots.

During the final stages of the war, the Japanese air force adopted a new tactic: kamikaze attacks. Named after the “divine wind” that had saved Japan from the Mongol hordes during the Middle Ages, kamikaze attacks were suicide missions undertaken by daring pilots willing to protect their country at any cost. Their planes were turned into massive flying bombs, which they flew directly into Allied ships to try and sink them.

Some planes used by the kamikaze pilots were old or inferior models which could be considered disposable. But such was the desperation of the Japanese military that even a superior N1K2-J Shiden-Kai was sometimes thrown away in one of these attacks.