Werner Meritz spent three months in Buchenwald. In 1938, he came to the U.S. and worked on a top-secret project called P.O. Box 1142. In 2006, it was revealed that the national park in Fort Hunt in Virginia was the location of the top-secret military project.

“These men were specifically recruited because they spoke German and because they understood the nuances of German culture and psychology, slang, cultural references, small details that an American would miss,” explained radio producer Karen Duffin.

Meritz recently recalled his actions during that time to rangers from Fort Hunt Park.

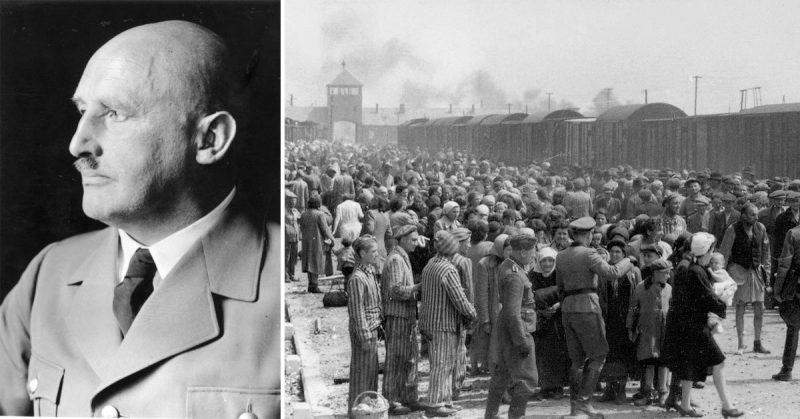

When the Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher was captured by the Allies, he was brought to Fort Hunt Park for interrogation. Streicher was a friend of Hitler and the publisher of the anti-Semitic paper, Der Sturmer.

When Meritz encountered Streicher, he “flipped out.” Meritz, whose mother and sister were killed in the Holocaust, locked the Nazi in a shed for three days.

“I told him, from now on, you sleep naked on this cold floor. You will not move,” said Meritz.

“And after, I pissed all over him. I said you’re just to lie there to get some sense of what you Nazis did to the Jews.”

“I was enraged and I was trembling. I had tears in my eyes that I had captured him. I explained to the MPs, I’m gonna do things you probably think I’m crazy. And you wanna know something? I am crazy. I’m crazed. I captured a Nazi of unbelievable mischief … I’m gonna do what I have to do.”

For three days, Mertiz fed Streicher only potato skins that he had urinated on. He then handed Streicher to the U.S. officers. Streicher was later sentenced to death along with ten other Nazis at the Nuremberg Trials. Meritz started his own textile business. He passed away in 2010. His daughter said that he was a sharp dresser who kept his mustache well-trimmed and had strong opinions.

The records of Streicher’s capture are “spotty and contradictory”. Usually, credit for his capture goes to someone other than Meritz. An expert at the National Archives felt that it was possible Meritz did exactly what he says he did.

If so, it was an exception to the way things usually went at P.O. Box 1142. The military had trained the interrogators to use nonviolent methods, going so far as to recommend being friendly with the prisoner.

Many Jewish interrogators were happy to help the U.S. beat the Nazis; getting friendly with the Nazi prisoners was difficult. The Jewish interrogators signed a secrecy agreement, so they did not discuss what they did, even with their wives and families. In 2006, Army intelligence allowed them to talk to the rangers.

P.O. Box 1142 was the first time the Americans made a strategic effort at interrogation. It worked. By the end of the war, much valuable intelligence had been gained.

When the war ended, the mission of the program was adjusted to recruiting Nazis to the American side – especially scientists who might be valuable to the Russians.

Arno Mayer, 88, escaped the Nazi occupation of Luxembourg. He eventually became a history professor at Princeton University. He received the task of charming Wernher von Braun, the rocket scientist who helped the U.S. space program get to the moon. Mayer recalled taking Nazis shopping at Jewish department stores in Washington D.C. He regrets not being more subversive.

“I should have told them to go to hell, but I didn’t do it. I was a coward. I mean I only exploded once. I could have exploded many other times.”