Kristallnacht was one of the darkest events to occur in the lead up to the Holocaust and World War II. Occurring on the night of November 9-10, 1938, the state-sanctioned pogrom saw synagogues burned down, Jewish businesses and homes ransacked, and tens of thousands of Jewish men arrested and sent to concentration camps.

What took place sent shockwaves across the world and served as a grim signal of the greater atrocities that would soon engulf Europe.

What was happening in Germany prior to Kristallnacht?

In the years leading up to Kristallnacht, Germany was under the oppressive rule of the Führer and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. The regime systematically marginalized and persecuted the country’s Jewish population, employing propaganda to scapegoat Jews for the country’s economic woes and societal issues. Anti-Jewish legislation had been enacted, stripping Jews of their rights and livelihoods, and fostering an environment of hostility and discrimination.

The Nuremberg Laws of 1935, in particular, revoked Jewish citizenship and prohibited marriages between Jews and non-Jews, and they were part of a broader effort to isolate and disenfranchise the Jewish community, making them vulnerable to further persecution. By 1938, the situation had escalated, with Jews being expelled from schools and professions, and their businesses boycotted.

The regime’s anti-Semitic policies weren’t only a reflection of deep-seated prejudice, but also a strategic move to consolidate power by uniting the German populace against a common enemy. As tensions rose, the Jewish community found themselves increasingly isolated, with limited options for escape or resistance, foreshadowing the horrors that were to come.

Assassination of Ernst vom Rath

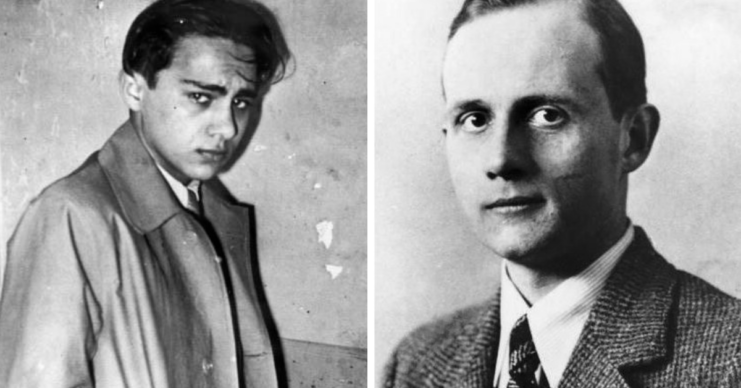

The assassination of Ernst vom Rath, a German diplomat stationed in Paris, was the catalyst for the events of Kristallnacht. On November 7, 1938, 17-year-old Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jew, went to the German Embassy in Paris and shot vom Rath in protest of the regime’s treatment of Jews – in particular, the expulsion of Polish Jews, including his own family, from Germany. Grynszpan’s loved ones had been forcibly deported, leaving them stranded and stateless.

The reason they were unable to return to Poland was that the Polish government had ratified a law that made it easier to strip any Polish person of their citizenship if they didn’t live in the country. This, along with another measure that canceled the passports of those who were living aboard and hadn’t received permission to re-enter Poland, meant it was impossible for them to return.

Grynszpan’s act was driven a desire to draw international attention to the plight of Jews under German rule, and it occurred amid escalating tensions between Germany and Poland. In the former nation, the assassination was seized upon by the Reichsleiter for inciting violence against Jews. He portrayed it as part of a larger Jewish conspiracy against Germany, fueling anti-Semitic fervor.

Kristallnacht – ‘Night of Broken Glass’

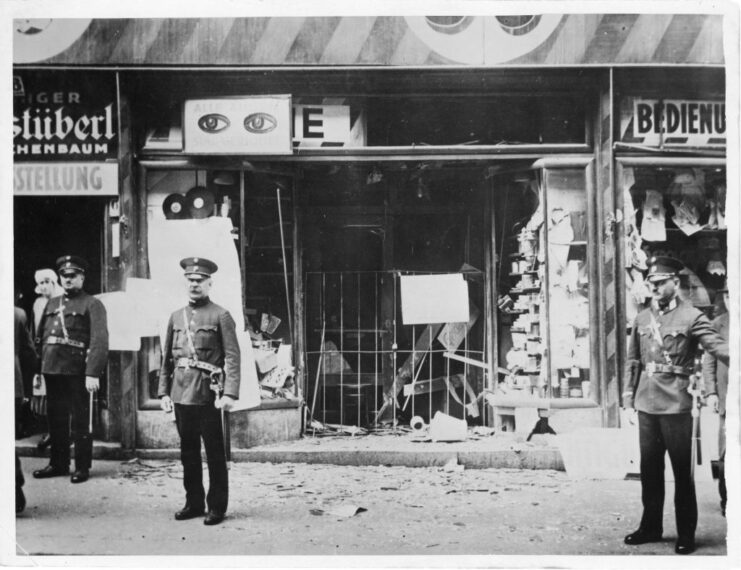

Kristallnacht (“Night of Broken Glass“) occurred on the night of November 9-10, 1938, as a state-sanctioned pogrom against Jews throughout Germany, the Sudetenland and Austria. The violence was orchestrated by government officials, including the Gestapo, SS, the Sturmabteilung (SA) and the nation’s Youth organization, under the guise of spontaneous public outrage. In reality, it was a coordinated attack, with orders to target Jewish businesses, synagogues and homes.

As night fell, Storm Troopers and civilians took to the streets, smashing windows, looting shops and setting synagogues ablaze. The destruction left a trail of shattered glass, giving the night its infamous name. Firefighters were instructed to let synagogues burn, intervening only to protect non-Jewish properties. Police stood by as the violence of the night unfolded, arresting Jewish men en masse.

Civilians, both complicit and passive, watched as the chaos ensued, with some participating in the looting and destruction. The Jewish community, caught off guard, was left to grapple with the devastation. Many sought refuge in their homes, while others attempted to flee the violence, only to find themselves arrested and sent to concentration camps.

Nearly 100 Jews were killed, thousands of businesses destroyed, hundreds (possibly thousands) of synagogues burned to the ground and more than 30,000 Jewish men arrested and deported to concentration camps – the first time the regime had imprisoned Jews on a large scale, simply because of their ethnicity and religion. Vienna and Berlin saw the worst destruction, given the size of each city’s Jewish populations.

‘Justifying’ the events of Kristallnacht

In the immediate aftermath of Kristallnacht, the German regime sought to rationalize the violence as a justified response to the assassination of Ernst vom Rath. Propaganda portrayed the pogrom as a spontaneous outburst of public anger, despite evidence of state orchestration.

International reaction was mixed, with widespread condemnation but limited action. The United States recalled its ambassador, while other nations issued protests. However, little was done to assist the Jewish refugees or challenge the regime’s actions, and many countries kept diplomatic ties with Germany.

Cleanup of the destruction was swift, with the Jewish community forced to bear the financial burden. A massive fine of one billion Reichsmark was placed on them, blaming Jews for the damage, and they were forced to handle the cleanup. The state confiscated insurance payouts, as well, and Jewish businesses were transferred to non-Jewish ownership.

The pogrom had served as a pretext for further anti-Semitic legislation, stripping Jews of their remaining rights and accelerating their exclusion from German society.

A turning point in Germany

Kristallnacht marked a significant turning point in Germany, as it transitioned from systemic discrimination to overt violence against the Jewish population. The pogrom shattered any sort of illusion as to the safety for Jews in the country, signaling the intent to escalate its campaign of persecution.

The international community’s muted response to Kristallnacht emboldened the regime, reinforcing its belief in the feasibility of its genocidal plans. The lack of intervention showed the limitations of diplomatic protests and highlighted the need for concrete action to counter the regime’s aggression.

The pogrom also served as a catalyst for Jewish emigration, with many seeking to escape the escalating violence. Unfortunately, restrictive immigration policies in other countries meant there were limited options, leaving many trapped in what could only be described as an increasingly hostile environment.

Legacy of Kristallnacht

Following the conclusion of the Second World War, hundreds of trials were held in relation to Kristallnacht. However, unlike the Nuremberg Trials, which were run by the Allied forces, these were conducted by German and Austrian courts, as the victims had not been from Allied nations.

More from us: Leonard T. Schroeder: The First Allied Soldier to Land on Normandy on D-Day

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

Kristallnacht is commemorated annually, with memorials and educational programs created to both preserve its memory and educate future generations about the dangers of anti-Semitism. They serve as a call to action, urging individuals and nations to stand against discrimination and protect the rights of all people.