WWII was the pinnacle of paratrooper action. The tactics and technology needed for paratrooper landings had been refined to a point where they could play a decisive role. The technology that would replace them, especially helicopters, was not yet a factor.

Early in the war, the Germans executed the largest paratrooper landing in history, on the Greek Island of Crete. Although not flawless, it was a success. In December 1944, they launched their last paratroop drop, with very different results.

Operation Autumn Fog

In the autumn and winter of 1944, Nazi Germany was in retreat. In the east, the Russians had turned the fighting around and gone on the offensive. In the west, Allied troops had seized control of northern France and steadily pushed the Germans back. American, British, and Canadian forces were making steady progress along the northern flank, while Patton raced into the industrial heartland further south.

Hitler responded with Operation Autumn Fog. A massive surprise attack through the Ardennes forest, it was meant to break the Allied line in two.

In support of the offensive, Oberst Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte was tasked with leading a paratroop drop. Landing behind American lines, Heydte and his men were to secure the route down which the Panzer divisions would advance following the breakthrough.

Building a Battlegroup

Heydte had served as a paratroop commander for most of the war. In October 1944, he had been disappointed to be moved from active service to training officers. His mood changed on December 8 when he discovered he was to lead the paratroopers in Operation Autumn Fog.

The first part of Heydte’s job was assembling a battlegroup. Every paratroop regiment was ordered to send him 100 fully qualified paratroopers. He was allowed to pick his own NCOs, officers, and planning staff. Within 48 hours, he had organized five companies and a signals and pioneer platoon.

Heydte had misgivings. He was unsure how well a hastily assembled unit with no shared experience could serve in the field, but he was a good soldier. He was a patriot who fought for the Nazis despite an arrest for punching one of them in the 1930s. He followed his orders.

Delays and Difficulties

Almost immediately, Heydte encountered problems. Supplies and parachutes were not delivered on time. He marched his troops to an aerodrome, only to find its commanding officer knew nothing about the mission. Senior Luftwaffe officers had not been told about an operation in which they were meant to collaborate with him.

Autumn Fog had already been delayed twice. The need for secrecy hindered preparations. Heydte and Major Erdmann, the commander of the squadron that would fly him into action, were not given the full picture.

Despite everything, they did their best to plan a paratrooper landing.

Freiherr Friedrich August von der Heydte

Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte commanded the operation. Bundesarchiv – CC BY-SA 3.0

A Brief Cancellation

On the night of December 14, tired and annoyed at the challenges facing them, Heydte and Erdmann were informed their mission was scheduled for 0300 on December 16. They had one day left to prepare.

On the evening of the 15th, new problems arose. Not enough fuel had been provided to get Heydte’s troops to the airfield. Only a third of his battlegroup, around 400 men, could go into action.

He reported to High Command, who canceled the drop.

At noon the next day, a call came through. Autumn Fog had not done as well as Hitler expected. There were worries the Americans would bring in fresh troops. The paratroop action was back on, this time to block the Americans.

Dropping into the Dark

That night, the whole battlegroup was brought to the airfield. They boarded their planes and set out.

The difficulties they faced proved disastrous. Their pilots were inexperienced and the drop time was miscalculated. Gale force winds and snow swept the area. Anti-aircraft fire scattered the planes.

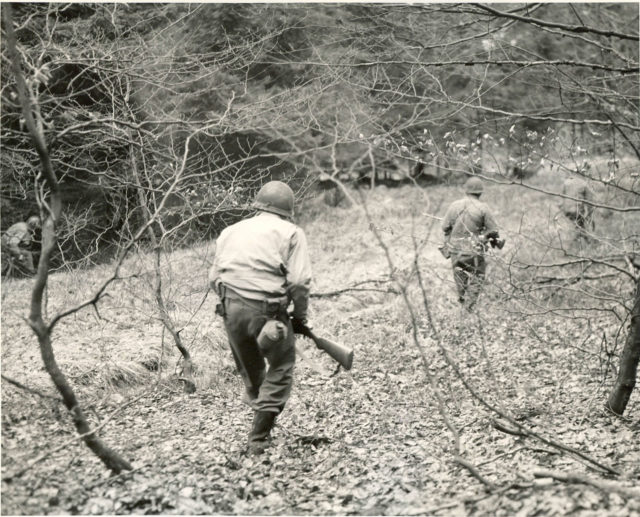

Dropped too early from planes out of formation, the paratroopers were snatched by the wind and spread across the countryside.

Scattered and Alone

Heydte survived a rough landing with a broken arm. He made his way to the first rallying point, a crossroads, gathering what men he could find.

By dawn, he had 125 paratroopers; less than a tenth of those he had set out with. Most of their weapon drops were missing. Their wireless was damaged, and they could not reach the army.

Heydte had his group take up defensive positions in the dense forest. He sent runners to reach German lines, but not one got through.

Elsewhere in the Ardennes, Hitler’s offensive had been halted and was being driven back. There was no chance of linking up with the army. Heydte had no way of learning what was going on or obtaining support.

Tactical Successes, Strategic Loss

Three days into his operation, Heydte met up with another 150 of his men.

The enlarged group clashed with American forces. They took prisoners and gathered important intelligence, but could not get either through to their lines. They left the prisoners behind with their first severely wounded comrade.

The Failed Breakout

On the fourth day, Heydte acknowledged there was only one option left. He had to break through the American lines and join the main German force.

The paratroopers headed east, crossing a stream of freezing water deep enough to reach their chests. On day five, they ran into American units supported by armor, which they were in no position to fight.

Heydte pulled his men back into the forest. He broke them up into three-man groups and set them to scatter once more across the country. Each band would do its best to survive and reach safety.

After finding shelter in civilian houses, on Christmas Eve, Heydte contacted the Americans and surrendered.

The last German paratrooper drop of the war had ended in utter failure.

Source:

Nigel Cawthorne (2004), Turning the Tide: Decisive Battles of the Second World War

James Lucas (1996), Hitler’s Enforcers: Leaders of the German War Machine 1939-1945