World War II ended in Europe on May 8, 1945. As for Southeast Asia and Oceania, peace only came several months later on September 2, when Japan finally surrendered. Except for one man, that is. For him, WWII only ended in 1974.

Our story begins in the Philippines – a Spanish colony until the Spanish-American War of 1898. To keep it short, the Spanish lost and the Philippines became American property.

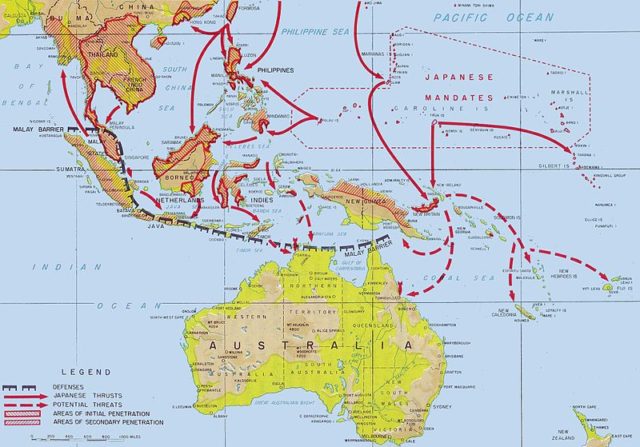

Fast forward to the 20 century. Japan wanted an empire in its backyard by taking Southeast Asia and Oceania. But there was a problem – various European nations owned almost all of it.

Ten hours later, while the Americans were still putting out the fires, Japan attacked the Philippines on December 8. The country’s central location gave Japan the staging post it needed to attack the rest of the region. Its vast resources also helped fuel the Japanese war effort, while the Filipinos made excellent (albeit unwilling) slaves. But there was another problem.

The Philippines is made up of over 7,000 islands (depending on whether or not it’s low or high tide). Taking a few didn’t mean that you had the rest, any more than taking out Pearl Harbor meant that the Americans were deprived of an army, a navy, and an air force.

So that left one final problem – the Americans weren’t going to give up their property without a fight. Enter Hiroo Onoda. Born in Kamekawa, Japan on March 19, 1922 to a samurai (warrior class) family, his career was set. At 18, he enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Army Infantry. Sent to the Nakano School (the main training center for military intelligence and unconventional warfare), Onoda became both a commando and an intelligence officer. On December 26, 1944 he was sent to Lubang Island in the Philippines to join the Sugi Brigade. Though Lubang is a tiny backwater, it lies a mere 75 miles southwest of the capital at Manila.

By then, the Japanese weren’t doing too well as the Americans were indeed fighting their way back. Onoda’s mission was: (1) to do whatever he could to slow the Americans through sabotage and guerrilla operations and (2) not to die.

According to his account, however, the men of the Sugi Brigade outranked him and prevented him from carrying out his orders. So when the Americans returned, they quickly and easily took Lubang on February 28, 1945.

While the rest surrendered, Onoda and three others did not. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant and put in charge of Private Yūichi Akatsu, Corporal Shōichi Shimada, and Private First Class Kinshichi Kozuka.

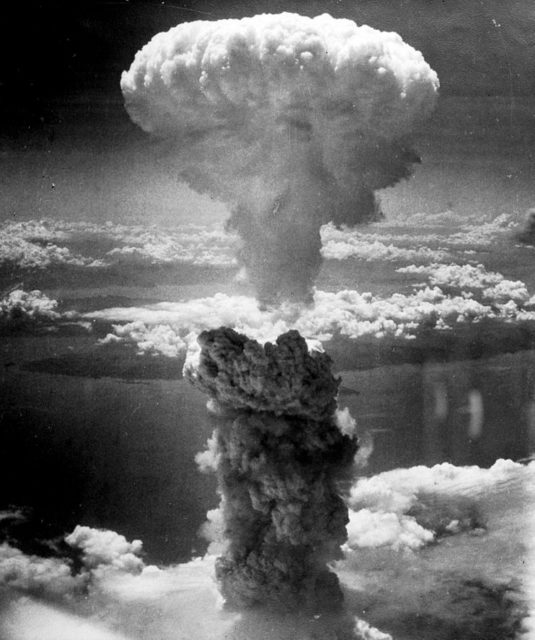

As the Americans and local fighters secured the island, Onoda ordered a retreat up the mountains. In August 1945, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were nuked, but the men stayed where they were. Japan formally surrendered the following month, but the group didn’t budge.

Knowing that there were still Japanese soldiers holding out all over the Pacific, the Americans took to the skies dropping leaflets to let them know the war was over. But Onoda and his men refused to believe it. They were convinced it was a ploy to get them to surrender, which they’d never do.

By the end of 1945, General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Fourteenth Area Army issued a surrender order which was also mass produced and dropped from the skies. The group concluded it to be a fake.

The men survived on coconuts, bananas, stolen livestock, and occasional late night forays into sleeping towns and villages. By September 1949, Akatsu had had enough, so he walked off and surrendered to the Filipinos.

Fearing they’d been compromised, the remaining three retreated deeper into the jungle to carry out Onoda’s original mission – sabotage. There were a number of skirmishes with the police and civilians, mostly farmers who weren’t too happy about giving up their livestock or their lives. As the death toll mounted, the hunt for the Japanese intensified. To the men, it was proof that the war was still being waged.

Desperate to flush them out, the Japanese government airdropped more pamphlets in 1952 – this time with pictures of the men’s families. Onoda again concluded that it was another trick. In June 1953, the trio had a shoot-out with some fishermen – one of whom shot Shimada in the leg. He survived, but was killed during another skirmish on May 7, 1954. Another such incident on October 19, 1972 took Kozuka, leaving Onoda alone.

For the next two years, farmers had to suffer the inconvenience of burning rice fields and stolen livestock, while Japan apologized profusely to the Philippine government.

After Kozuka’s death, they resorted to chucking Japanese newspapers out of planes, as well as personal letters from family members and former comrades, but Onoda didn’t buy any of it. It took a college drop-out to do it, but they didn’t have to chuck him out of a plane. Norio Suzuki was a self-professed adventurer, his goal being to find Onoda, see a panda, and discover the Abominable Snowman – all in that order. On February 20, 1974 Suzuki got his first wish, but Onoda still refused to surrender “What’ll it take?” Suzuki asked. “A direct order from my commanding officer,” was the reply.

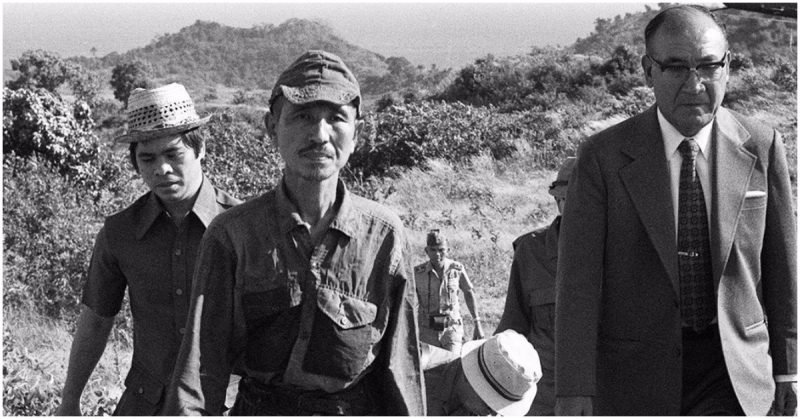

So Suzuki returned to Japan and found Major Yoshimi Taniguchi. Taniguchi flew back to Lubang and formally relieved Onoda of his duty on March 9, 1974 – 29 years after WWII ended. Delighted to see him leaving, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos officially pardoned Onoda of multiple homicide a few days later. Onoda returned to Japan and set up a survival-training school for children, hoping it would toughen them up. He later died on January 16, 2014.