Some 16,859 American soldiers call the Manila American Cemetery their final resting place, making it the largest US site of World War II dead. It’s located in the capital city of the Philippines, which witnessed a number of atrocities during the conflict, including the carnage that resulted from the battle for its liberation toward the end of the war.

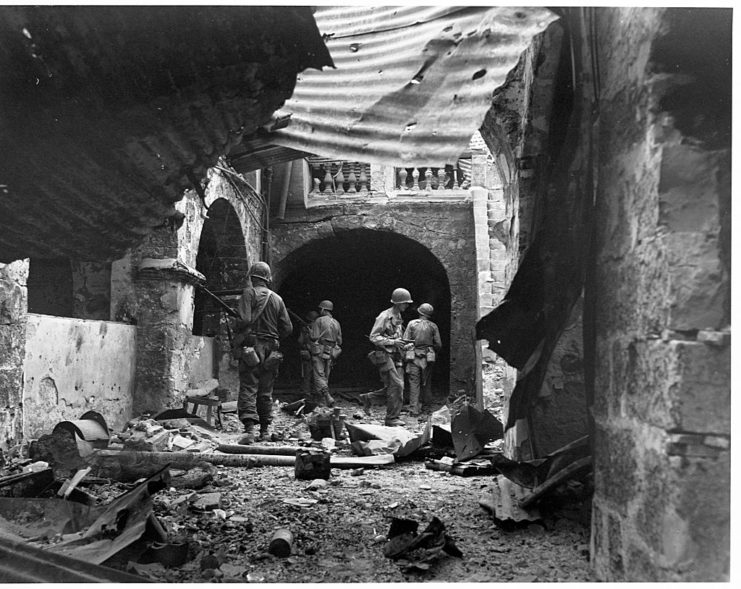

The horrific cost of war in Manila

Manila became one of the most destroyed capital cities of Second World War, and was the most devastated in the Pacific Theater. The Battle of Manila in 1945 raged for a month, as US troops liberated the city from the Japanese, who’d occupied it since their invasion of the Philippines in 1941-42.

Weeks after the Japanese invasion of the Philippines, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt made a pledge for the countr’s freedom, saying, “The people of the United States will never forget what the people of the Philippine Islands are doing this day and in the days to come. I give to the people of the Philippines my solemn pledge that their freedom will be redeemed. The entire resources in men and material of the United States stand behind that pledge.”

Not long before the invasion, the US Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) had created, under the commander of Gen. Douglas MacArthur. It consisted of 100,000 Filipinos and 20,000 Americans working together to delay the advancement of the Japanese. Unfortunately, they were placed on half-rations a month after the invasion began, and when they surrendered in April 1942 following the three-month Battle of Bataan, they were starving and suffering from a string of diseases.

The captured soldiers were forced to walk between 60-69 miles through the jungle to their prison camp, in what became known as the Bataan Death March. They were given no food, water or shelter. Those who could no longer walk were killed.

Manila American Cemetery

The Manila American Cemetery is located in Fort Andres Bonifacio, Taguig, Metro Manila, within the boundaries of what used to be Fort William McKinley. Spanning 152 acres, it’s home to 17,206 gravesites, including the aforementioned 16,859 American dead from WWII. War dead from other Allied countries were also laid to rest here, as were the bodies of over 3,000 unknowns.

The Manila American Cemetery features gravestones in the shape of crosses, which are made from marble. At the center of the site sits the chapel, a white masonry building with sculptures and 25 mosaic maps, which trace the achievements of the American forces throughout the Pacific Theater.

Beyond the white crosses lie the Tablets of the Missing, inscribed with over 36,000 names. Those who have since been identified have had rosettes placed beside their names, indicating they’ve since been given back their identities.

Final resting place of the Sullivan Brothers

The majority of servicemen buried at the Manila American Cemetery either lost their lives during the Battle of the Philippines in 1941-42 or while fighting on New Guinea. Buried among the fallen are 23 recipients of the Medal of Honor.

The Sullivan Brothers, whose deaths influenced to the creation of the Sole Survivor Policy, are memorialized at the site. The five enlisted in the US Navy in January 1942, on one condition: they be allowed to serve together. They were subsequently assigned to the light cruiser USS Juneau (CL-52), which participated in a number of naval battles during the Guadalcanal Campaign.

On November 13, 1942, during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Juneau was struck by a Japanese torpedo and forced to withdraw. Later that day, she was hit again, this time by a torpedo fired from the Japanese submarine I-26. The impact led to an explosion, which subsequently sunk the light cruiser.

While the majority of the onboard died in the initial blast, 100 survived. Sadly, due to shark attacks and exposure to the elements, only 10 of that total wound up being rescued. Among the crewmen to perish that day were the “Fighting Sullivan Brothers,” who are remembered as national heroes.

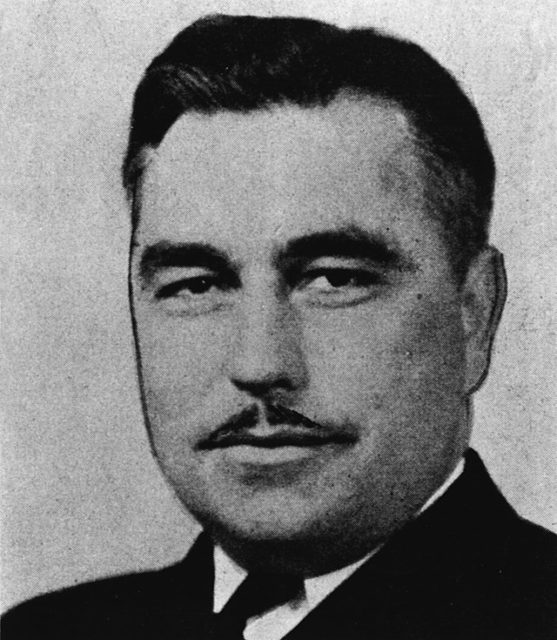

Ernest E. Evans is listed on the Tablets of the Missing

Medal of Honor recipient Ernest Edwin Evans is listed on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery. He was posthumously awarded the decoration for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as commanding officer of the USS Johnston in action against major units of the enemy Japanese fleet during the battle off Samar on 25 October 1944.”

Having served with the US Navy for a number of years, Evans was placed in charge of the USS Johnston (DD-557), a Fletcher-class destroyer, during her deployment to the Pacific Theater. Early into his command, in May 1944, he was awarded the Bronze Star for the sinking of Japanese submarine I-176.

Evans was a key player in the Battle off Samar, one of the major offensives during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. He outmaneuvered the enemy throughout the engagement, and provided selfless and unwavering support for his men, even as Johnston suffered hit after hit from the Japanese.

More from us: Henry Fonda Served In the US Navy During WWII – He Didn’t Want to ‘Be a Fake In a War Studio’

No one’s exactly sure how Evans perished during the Battle off Samar. All that’s known of his final moments is that he lived long enough to give the order to abandon ship before Johnston sunk below the water on October 25, 1944.