World War II produced a number of heroes, particularly within the US military. A total of 473 service members were presented with the Medal of Honor, the country’s highest decoration for acts of valor and selflessness in combat. US Marine Mitchell Paige was one of the individuals to receive the award, and upon his death in 2003 was the last surviving recipient from the Guadalcanal Campaign.

Mitchell Paige’s entry into the US Marine Corps

Mitchell Paige was born on August 31, 1918 in Charleroi, Pennsylvania. From a young age, he had a high respect for the military and looked forward to watching veterans from the First World War march in his town’s annual Armistice Day parade. Given this, it’s no surprised that he enlisted in the US Marine Corps the minute he turned 18, hitchhiking to the station in Baltimore, Maryland, some 200 miles away.

After completing basic training at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, Paige was transferred to Quantico, Virginia to serve with Company H, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division. He later served as a gunner aboard the USS Wyoming (BB-32) while the vessel took part in maneuvers off the coast of California. Paige continued in this role until February 1937, when he was transferred to Mare Island Navy Yard for guard duty and, later, to Cavite in the Philippine Islands.

From October 1938 to September 1939, Paige guarded American property in China, after which he returned to the US for guard duty at both the Brooklyn and Philadelphia Navy Yards. He rejoined the 5th Marine Regiment in September 1940 for maneuvers in Cuba, Puerto Rico and Guantanamo Bay, before being sent back to the US to help in the construction of what later became Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune.

Manning four machine guns on Guadalcanal

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Mitchell Paige was set to Apia, British Samoa with the 7th Marine Regiment. By September the following year, he and his comrades landed on Guadalcanal to participate in the American forces’ first major land offensive against the Japanese.

“By the time I got to Guadalcanal, I’d been a machine-gunner for six years,” he later recounted when speaking with the Marine Corps Association. “I was a platoon sergeant, and I required every Marine in my platoon to be able to fieldstrip the water-cooled machine gun, the 1903 Springfield rifle and the .45-caliber pistol. They could do it blindfolded; take it apart and put it back together. Every man.”

On October 26, 1942, during the Battle for Henderson Field, Paige and his men were positioned on a saddle hill, between the F and G companies of 2nd Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment. At around 2:00 AM, he heard Japanese soldiers speaking around one hundred yards away, which prompted him to ready his men for the impending attack. It was then that artillery fired from Japanese-manned howitzers began to bombard their position.

Faced with an estimated 2,700 Japanese soldiers, Paige’s platoon of 33 quickly became overrun. Determined to defend the ridge, he solely operated the company’s four machine guns, calling for reinforcements in the process. When the guns were destroyed, he led a bayonet charge against the remaining Japanese soldiers, despite not having enough men to successfully pull off the move. Luckily, the enemy didn’t realize this and was driven off.

“I was so wound up at this point, I couldn’t stop,” he recalled. “I yelled back to the riflemen, ‘Fix bayonets; follow me.’ I threw two belts of ammo over my shoulders, unclamped the machine gun, picked it up and cradled it in my arms after loading it.”

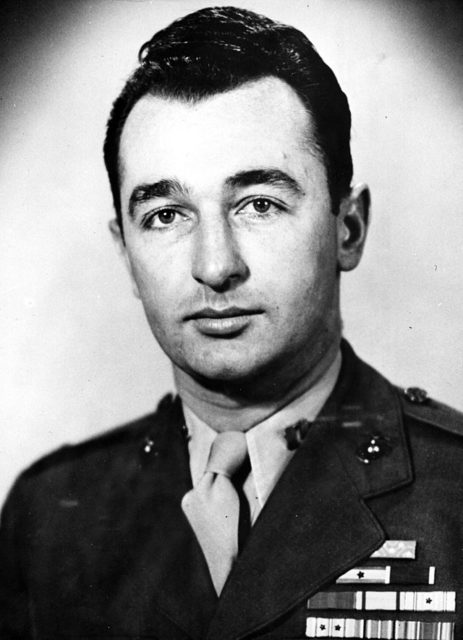

Mitchell Paige was presented with the Medal of Honor

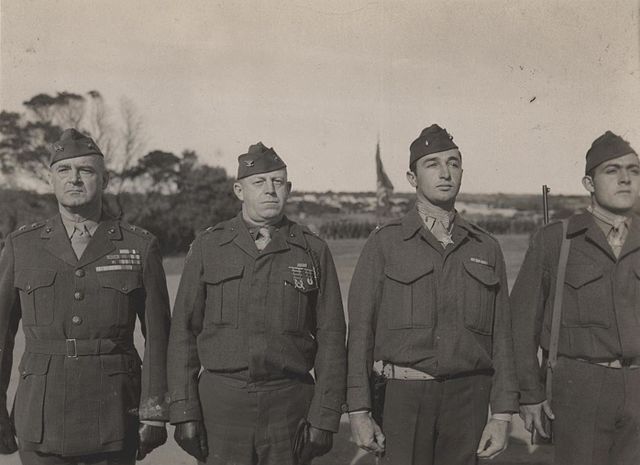

Mitchell Paige remained on Guadalcanal until January 1943, at which point the now-second lieutenant was sent to Melbourne, Australia with the 1st Marine Division. While there, he was presented with the Medal of Honor by Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, who told him that he was “the first enlisted Marine in my division to be awarded this medal.” According to SFGate, Paige responded by saying, “This Medal of Honor belongs to all 33 men in my platoon on Guadalcanal.”

In September 1943, the Marine left for New Guinea with his division, where he and his comrades joined the US Sixth Army for the Battle of Cape Gloucester. The 1st Marine Division left for the Russell Islands in Pavuvu in May the next year, with Paige later sent back to the United States and assigned duty at Camp Lejeune.

While stationed in the US, Paige reached the rank of captain, after which he was promoted to the position of Tactical Training Officer at Camp Calvin B. Matthews and, later, as a recruit training officer at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego.

Remaining in the United States during the Korean War

When the Second World War came to an end, Mitchell Paige was placed on inactive duty, only to be reactivated four years later at the onset of the Korean War. He never saw service overseas during the conflict, and was instead ferried between the many Marine Corps installations across the US.

Between 1950-57, Paige held such positions as the Plans and Operations Officer of the 2nd Recruit Training Battalion at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot; division recruiting officer with the 2nd Marine Division at Camp Lejeune; and as the officer in charge at the Division Non-Commissioned Officers School with Sub-Unit #2, Headquarters Company, Headquarters Battalion, 3rd Marine Division in San Francisco – and that’s only scratching the surface of all he was tasked with doing during this time.

In May 1959, the now-lieutenant colonel joined the US Army Language School in California, where he remained until he was ordered to the Marine Barracks, US Naval Station, San Diego to take the role of executive officer. Just a few months later, he was placed on the Marine Corps Disability Retired List, effectively ending his military career, and promoted to the rank of colonel for being specially commended for performance of duty in combat.

Over his decades in the Marine Corps, Paige was the recipient of a number of awards. Along with the Medal of Honor, he received the Purple Heart, the American Defense Medal with one Bronze Star, the Presidential Unit Citation, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two Bronze Stars and the China Service Medal, among other decorations.

Mitchell Paige protected the integrity of the MoH until his death

Despite not serving with the military during the Vietnam War, Mitchell Paige worked as an advisor during the testing of high-powered rockets. In 1975, he wrote and published his memoir, titled A Marine Named Mitch: An Autobiography Of Mitchell Paige, Colonel, U.S. Marine Corps Retired, after some encouragement from actor and fellow Marine, Lee Marvin. It was a hit within the Marine Corps, with the branch making it a part of its Professional Reading Program.

That wasn’t the only time Paige would enter the spotlight. In 1998, he was the model for the Marine Corps figure in a series of G.I. Joe action figures honoring recipients of the Medal of Honor from each branch of the military.

Being a Medal of Honor recipient, Paige was dedicated to protecting the meaning behind the award. During his later years, he teamed up with the FBI to identify imposters selling and/or wearing the medals, and even successfully lobbied for an increase in the penalties for doing so. Speaking with Newsday about the experience, he said, “I couldn’t arrest these guys before I got together with the FBI, but I scared the hell out of them and even got some of the medals back.”

More from us: Al Schmid: The US Marine Who Continued to Man His Machine Gun After Taking a Grenade to the Face

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

On November 15, 2003, Mitchell Paige passed away from congestive heart failure at his home in La Quinta, California. The 85-year-old was buried at Riverside National Cemetery with full military honors.

Today, the museum at Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Twentynine Palms is dedicated to Paige. Additionally, the Eldrid World War II Museum in Pennsylvania has an exhibit for the Marine, named “Mitchell Paige Hall,” which features his Medal of Honor and other memorabilia he donated prior to his death.