Image Source: Wikipedia

World War I was devastating because offensive technology had superseded defensive ones, leading to catastrophic death rates. Britain was especially vulnerable since it depended on shipping, something the Germans threatened with their submarines.

Although hydrophones and depth charges helped turn the tide in Britain’s favor, there was one other thing that did the trick – art. More specifically, modern art, which also helped the Allies win WWII.

Image Source: <http://www.moma.org/collection/works/80430>

When Cubism was first developed in the early 20th century, most critics hated it. Cubists take an object and present it in abstract form to give it greater depth and texture. Pablo Picasso’s 1910 “Girl with a Mandolin” is a perfect example of Cubism and explains why so many were outraged by it, given their preference for traditional Classical Realism.

But while critics were busy lambasting this new art, WWI broke out in Europe. German submarines began sinking ships around British waters, not because they hated Cubism, as well, but because they were trying to choke off Britain’s supply lines.

In 1914, British zoologist John Graham Kerr wrote to Winston Churchill (then the First Lord of the Admiralty) to suggest a unique way of protecting ships. To understand his idea, you first have to understand how submarine warfare worked back then.

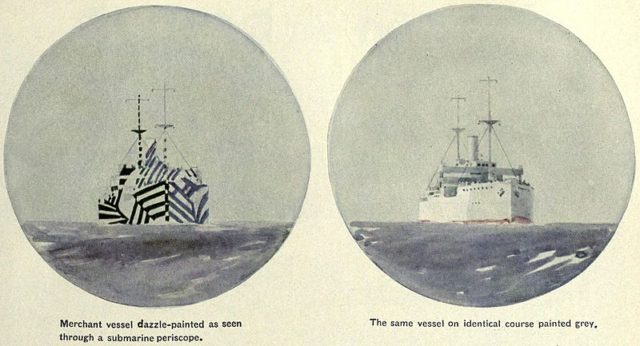

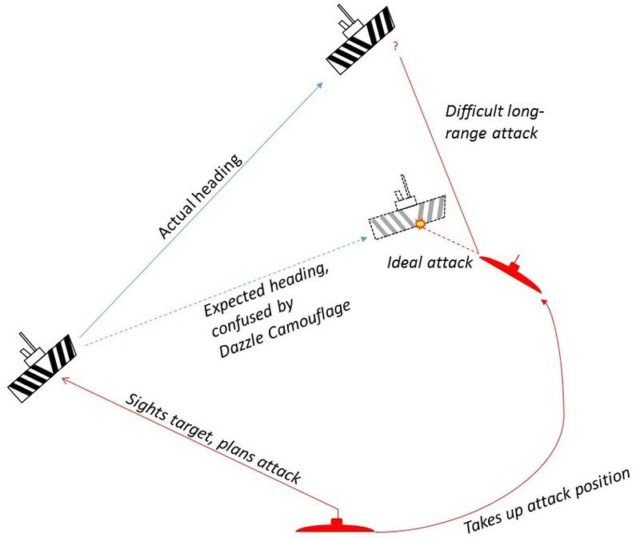

The technology was new and very primitive, so torpedoes could only be fired using line-of-sight. But since water slows torpedoes down, gunners had to compute: (1) their target’s speed, (2) its direction, and (3) their distance from it.

Image Source: Ian Alexander CC BY-SA 4.0

And all this had to be done from the limited visual that a periscope provided. Once they got all that, they had to fire ahead of the ship and hope the two met. Fire at the ship, itself, and the thing would have moved on because the British weren’t stupid – the moment they set sail, it was at full speed in an attempt to avoid German U-boats.

Kerr suggested using camouflage to hide ships. Though a great idea, it can’t be done because the sea, sky, and weather always changes, as does the water level around a ship. The Admiralty therefore continued painting their vessels a single color to the delight of the Germans who kept sinking them.

Image Source: <http://www.flashpointmag.com/blast_dazzleships_wadsworth.htm>

Enter Abbot Handerson Thayer. An American artist, he said pretty much the same thing that Kerr did… which was why Churchill ignored him, as well. Unlike Kerr, however, Thayer wasn’t about to take “no” for an answer, so he braved a trip to Britain and demonstrated his theories on a nationwide tour.

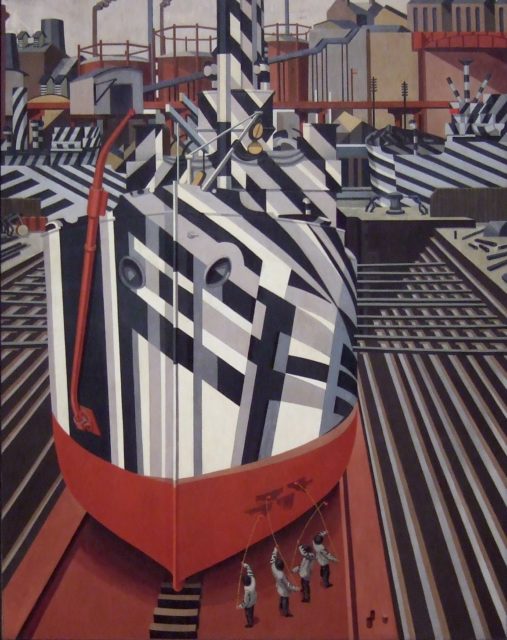

Norman Wilkinson, a marine artist with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, attended one of Thayer’s presentations and was convinced. Because while Kerr sought to conceal, Thayer sought to confuse.

Image Source: Wikipedia

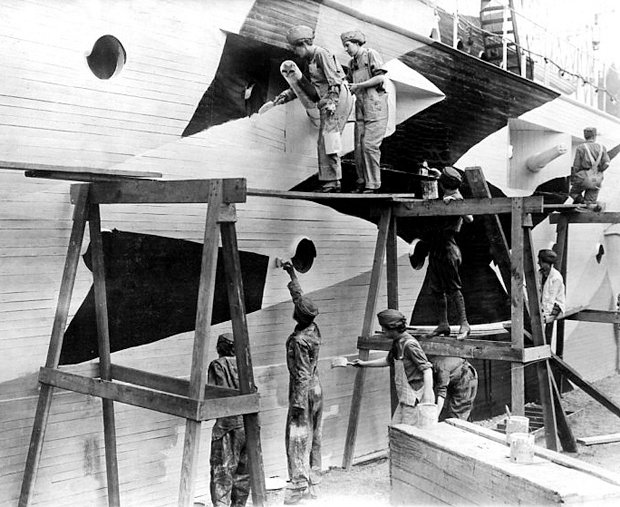

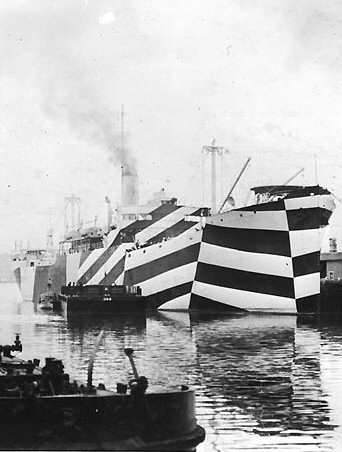

Painting a ship so one can’t tell where the front, side, or back is made it harder for a submariner to: (1) gauge its direction, (2) its speed, and (3) how far away it was. In an era before guided missiles, a gunner’s chances of hitting a moving target depended on a combination of luck and skill.

Thanks to Wilkinson, the dazzle-ship was invented. It’s believed that their zebra-like exterior may have thrown an experienced gunner’s aim off by up to 55°, giving dazzle-ships a fighting chance.

Image Source: Matěj Baťha CC BY-SA 2.5

British artist Edward Wadsworth oversaw the painting of over 2,000 ships, making sure that each one was unique to prevent the enemy from identifying the different classes. When Picasso saw them, he claimed credit for having invented the idea behind them.

The Americans were sucked into WWI because the Germans weren’t discriminating about who they sank. As such, it didn’t take the US long to get dazzle-ships of their own.

Image Source: <http://gizmodo.com/the-forgotten-history-of-how-modern-art-helped-win-worl-1002161699>

Though WWI ended, Cubism did not. It affected fashion, décor, and even architecture. Governments became fascinated with the idea of manipulating human perception to deceive the enemy or hide things in plain sight.

After their disastrous losses on the Western Front, the French gave up their blue coats and red trousers in favor of grayish horizon-blues. Still, it wasn’t enough. Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola, a French painter who was influenced by Post-Impressionism (a rejection of Classical Realism) and Cubism, was tasked with creating a camouflage unit, something other countries took up.

Image Source: <http://gizmodo.com/the-forgotten-history-of-how-modern-art-helped-win-worl-1002161699>

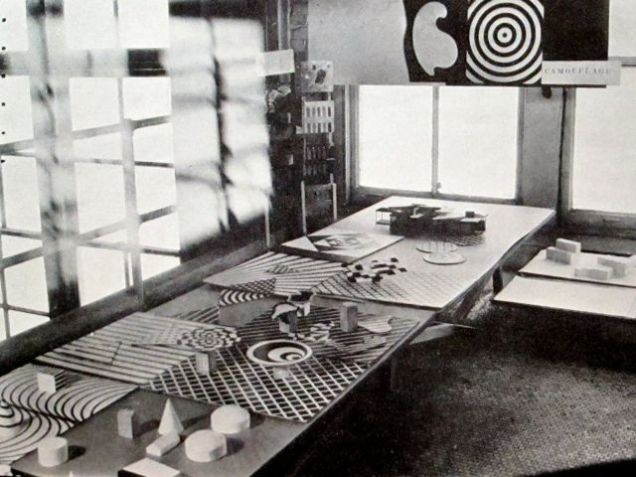

Advances in radar technology rendered dazzle-ships useless when WWII broke out, but not their basis. Abstraction, Cubism, and Realism contributed to better camouflage uniforms, but artists had another challenge to deal with – the development of infrared for aerial reconnaissance.

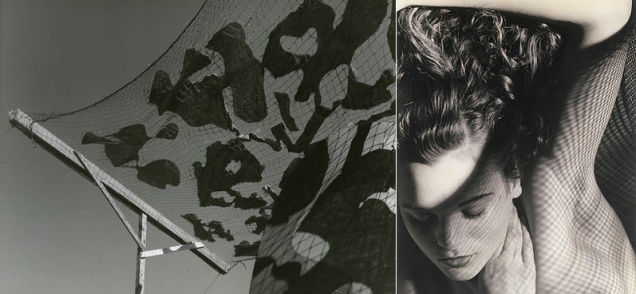

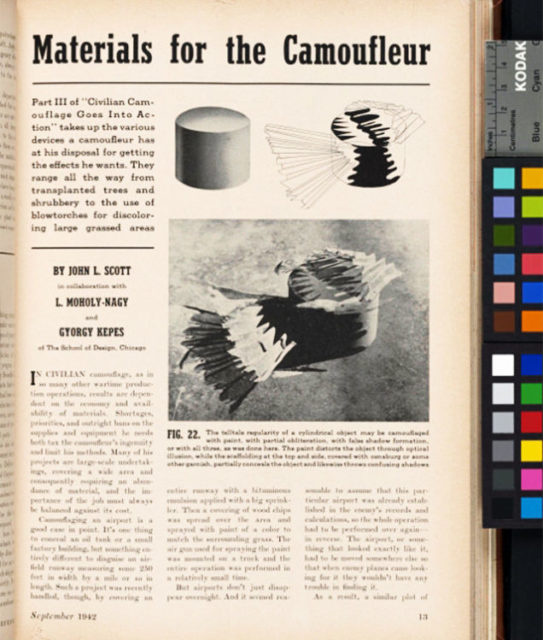

Max Dupain (an Australian photographer and Surrealist) found himself working with the likes of Roland Penrose (a British Surrealist), László Moholy-Nagy (a Hungarian-American painter and photographer), and others.

Image Source: <http://gizmodo.com/the-forgotten-history-of-how-modern-art-helped-win-worl-1002161699>

Dupain had experimented with black-and-white pictures of people, his most famous being “Jean with Wire Mesh.” Though nothing spectacular by today’s standards, it had a profound impact on photography because of the way it gave the model a diaphanous look. Thanks to Dupain, the modern netting used to hide planes and bunkers on the ground was born.

Moholy-Nagy, who had studied at the Bauhaus (an arts and crafts school in Germany) before fleeing to the US, was famous for his kinetic sculptures and paintings which play with the eye. He later taught at Chicago’s School of Design and was tasked with camouflaging Chicago after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Penrose was tasked with the same for Britain, using nets and colored cloth to hide airfields and military bases.

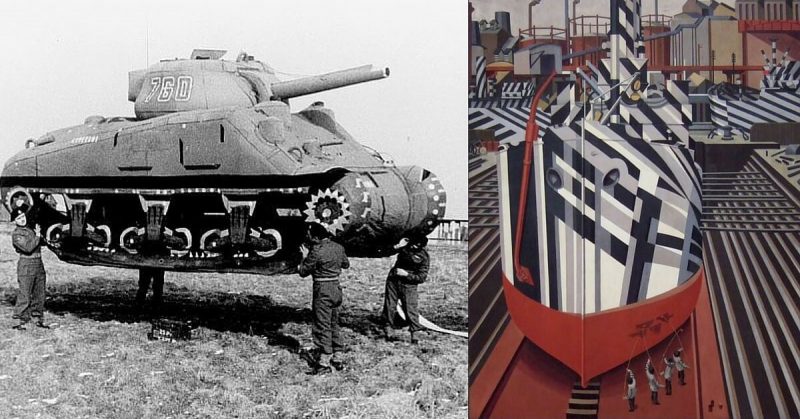

Artists were recruited into the 603rd Camouflage Engineers, also called the Ghost Army. These used props, sound, and fake radio signals to fool the Germans into believing the Allies were where they weren’t. Most were from the art schools of Philadelphia and New York, and included the likes of fashion designer Bill Blass, painter and sculptor Ellsworth Kelly, and photographer Art Kane.

Lest you think it was all about deception, however, modern art has also been used for propaganda. In 1995, the CIA admitted that it hired Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko to counteract Soviet-style Social Realism during the Cold War.

Image Source: Utilisateur:Ratigan CC BY-SA 3.0

Little is known about this because of both sides. On the one hand, governments want their techniques and operations kept secret. On the other, artists would rather not be associated with the establishment.

However you may feel about modern art, consider how different our world might have been had the Nazis won WWII. Think about that the next time you look at an art piece!

Image Source: Wikipedia