Both a recognized poet and a fearful warrior, Musa Calil won the highest Soviet literary prize as well as the Hero of the Soviet Union award. Both the awards were given posthumously, as the Nazis executed Calil in 1944.

His contribution to the Soviet war effort against the Nazis on the Eastern Front became something of a legend. He was captured by the Nazis, pressed into service with a collaborationist legion, only to organize a massive defection by his entire unit which joined the Belarus partisans, and ultimately the Red Army.

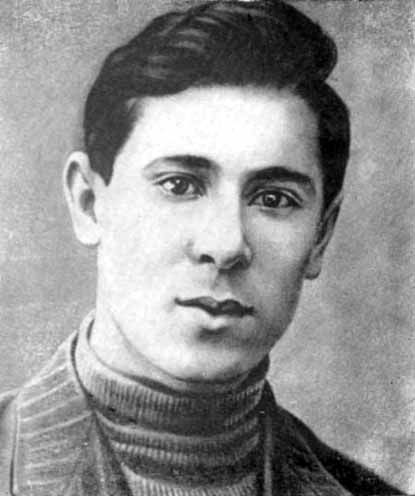

Musa Calil (Jalil in English) was born in Mustafino, a village in Orenburg Governorate. He was of Tatar descent, a Turkic people that widely adopted the Muslim religion. He was schooled in the Madrasa in Orenburg, where he became acquainted with traditional Turkic poetry and its authentic rhythm called the Aruz wezni.

He became a Bolshevik activist in 1919. He joined an underground cell of Komsomol, the Bolshevik youth organization, in Orenburg, which was at the time still under royalist control. Working in clandestine conditions during the Russian Civil War, he obtained training as a propaganda officer, where he used his writing skills in the service of the revolution.

He rose through the ranks in the Komsomol and moved to Moscow, where he was influenced by the poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky, the famous Russian futurist writer. He attended the University in Moscow and became a respected intellectual whose poetry was acknowledged by the people, as he wrote about the struggle of the Soviet common man.

The commencement of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the USSR began in 1941. Calil joined the ranks of the Red Army, but his talents were seen as too valuable to be squandered on the frontlines. He was appointed as a war correspondent, working to boost the morale of both the army and the people.

Witnessing the horrors of the Eastern Front left the young poet scarred. During the months he spent as a correspondent, Calil wrote poetry in which he meditated on subjects such as the effect war has on ordinary people.

In June 1942 the unit to which Calil was attached got caught in an encirclement during a failed attempt to break the siege of Leningrad. Musa Calil was lucky enough to get captured. He was sent to various POW camps for Soviet prisoners. He spent time in Stalag-340 in Daugavpils, Latvia, and Spandau, before he was transferred to Nazi-occupied Poland, to the Deblin stronghold.

There the Germans organized auxiliary units from the prisoners. Anti-Soviet sentiment was on the rise among the Russian prisoners. The Nazi regime had collaborators in the occupied territories of the USSR. The option to organize such units was realistic as the prisoners were disgruntled with the Soviet leadership and the general lack of essential supplies during wartime.

Musa Calil was appointed to serve with the Volga-Tatar Legion, due to his ethnic background. He used an alias name, Gumeroff, as he would have been executed if the Germans had learned of his real identity. An execution of a poet held great symbolic potential, for he was the one who drove the morale of his countrymen.

Calil held his cover intact and managed to infiltrate the Wehrmacht propaganda unit, which printed out anti-Soviet posters and leaflets. Around the printing presses of the Reich, he started to rally conspirators.

He was determined to undermine the German authority within the Legion and stage a coup when an opportunity occurred.

He wrote and printed pamphlets right in front of the watchful eye of the Germans. Agitation was Calil’s specialty, and he won the hearts of his countrymen through careful planning and inspirational speeches he held in secrecy. It was a very risky endeavor as he could easily have been betrayed. When the Volga-Tatar Legion was sent to the Eastern Front, they mutinied and executed their commanding officers. They then defected to the Belarus partisans who were under the direct control of the Red Army.

Then the Volga-Tatar Legion was sent to the Eastern Front, where they mutinied and executed their commanding officers. They then defected to the Belarus partisans who were under the direct control of the Red Army.

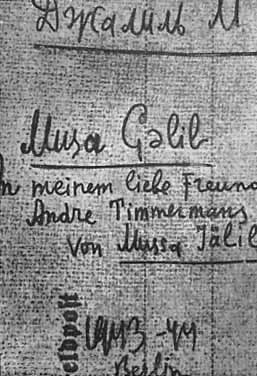

Calil’s plan had worked, but he was discovered and arrested by the Gestapo together with twelve of his comrades on August 10, 1943. The poet was sent to the Moabit prison in Berlin where he briefly shared a cell with a Belgian resistance fighter called André Timmermans.

His execution was prolonged, and he wrote poetry to keep his mind from the reality. Musa Calil compiled his verses in two notebooks, both of which were miraculously preserved by his friends.

He was finally executed on August 25, 1944, by guillotine.

Calil’s Belgian cellmate saved one notebook that made it back to the Soviet Union. The other was preserved together with the writings of another imprisoned poet of Tatar descent. Ğabbas Şäripov and Niğmät Teregulov were responsible for the safekeeping of the other notebook, but they were imprisoned after the war, as they were accused of treason.

Calil was also charged with treason after the war as his work in creating the mutiny by the Legion was unknown to the Soviet authorities.

It was not until 1953 that the Moabit Notebooks were published after the Tatar writers together with the Tatarstan department of security urged an investigation which revealed Calil’s underground activity during his capture.

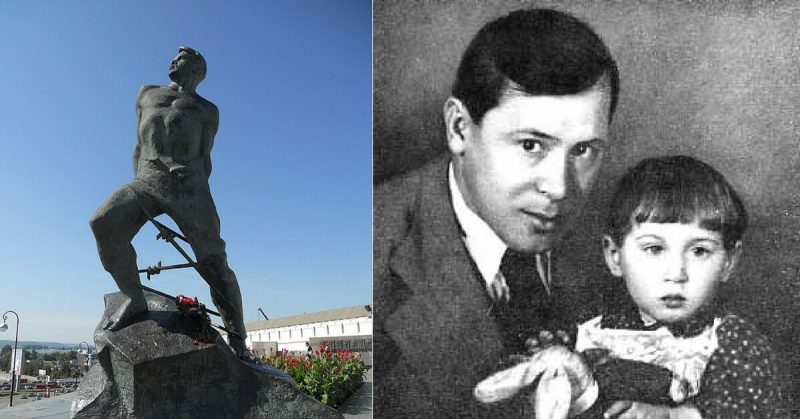

A Russian translation was published, and his poetry was acknowledged. As well as the awards that were given to him posthumously, a number gestures were made to honor the heroic poet. They include several monuments in Kazan, Orenburg and Moscow, an opera about his life, and a library that bears his name in Romania. There is even a small planet that was named after him by the Soviet astronomer Tamara Mikhailovna Smirnova who discovered it in 1972.