FROM HISTORIES OF THE NORMANDY LANDINGS PREPARED BY THE ARMY HISTORICAL DIVISION. – By W. C. HEINZ

Thank you to our friends at OldMagazineArticles.com for the use of this article

It was about ten o’clock in the morning when we reached the crossroad just west of Formigny. The mist was still blowing inland off the Channel, coming across the green fields and between the trees.

Ten years had passed since the American had been here, but he remembered the crossroad very well — the calvary on the one corner and the battle monuments on the three others — and he turned his small gray Peugeot to the right and drove down the narrow, winding blacktop, hemmed in between the thick bulk of the hedgerows, until it widened out where the new road curves through the center of Vierville-sur-mer.

“The Vierville church,” he said now, measuring the words and standing there and looking up. “A lot of Americans who landed on the beach will remember the Vierville church.”

Next to the church is the walled graveyard, built up above the surface of the road. The church itself is gutted still, the roof gone and only a few fragments of stained glass still sticking in the windows, but from the front a new steeple points up into the sky.

“The Vierville church,” he said again. “Bud, that was one of the old landmarks we studied a lot in England before the invasion. We studied it over and over.”

The boy said nothing. He is fourteen years old now, named after his father, and has brown, slightly wavy hair and blue eyes. He was wearing crepe-soled shoes and blue jeans, a blue plaid shirt and a red corduroy jacket, and all of his memories of the war are involved with the small white house with the big mulberry tree in the back yard on South Bridge Street in Brady, Texas.

There was a hut in the tree, and the small boy would play there and, in the mornings, he would stand in the front yard and watch the trucks filled with German Prisoners heading out to the farms. In the late afternoons, he would see them come back, and he remembers the machine guns on the trucks and the Germans neither laughing nor shouting but just standing in the trucks as they went by. Now the boy looked up at the steeple.

“You haven’t any idea how that old church used to worry us,” his father said.

“Why’?” the boy said.

“Because of the observation it gave the Germans,” his father said, “The Channel is only about a half mile down the road here, and the Germans used all these church steeples for observation. That’s why we had to shoot the steeple down.”

Postgraduate Work in trenchdigging

In 1932, James Earl Rudder had received his academic degree and his commission as a second lieutenant, Infantry Reserve. He had played center for Malty Dell, but that first summer, at the height of the depression, he dug ditches. From 1933 to 1938 he coached football and taught at Brady High School. He was coaching at John Tarleton College in Stephenville, Texas, when he went on active duty in 1941 at Fort Sam Houston.

“It’s a funny thing,” Rudder said. “We shoot down the steeple, and that’s the first thing the French build back, even before they build the church.”

He drove through the small intersection of the town. Two houses away from one corner two workmen were just starting to put back the stones that had lain in a pile for 10 years, and as the car went by they stopped. turning to watch it, Then Rudder drove down a slight slope that bent around to the left between hedgerows, and as the car came out of the curve, still on the slope, you could see a large new yellow fieldstone house, still not completed, and, straight ahead, the gray-blue waters and the mist above them.

“There’s your English Channel, Bud,” he said.

“There?” the boy said.

“That’s right, and that’s where we came in, the men who didn’t hit the cliff. A lot of American soldiers came up this road we’re on now, because it was the main exit road for everybody who came in on this end of the beach.”

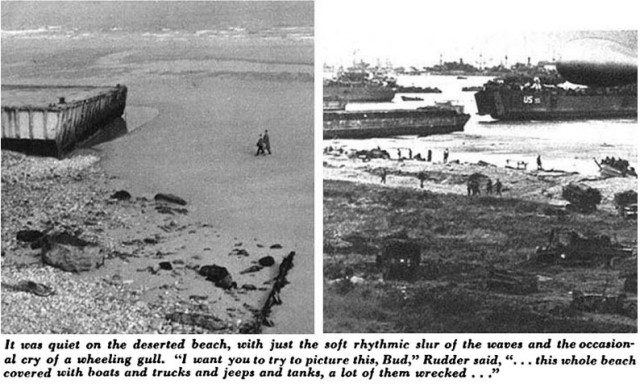

The car was stopped in the middle of the sloping road, and the man and the boy just sat there, looking down across the top of the two German concrete emplacements and at the tilted hulk of a hollow concrete floating pier that had been driven by a storm onto the shore. Then Rudder released the brake and the car rolled down the road toward the emplacements and then stopped on a wide, sweeping curve.

“And there’s Omaha Beach.”

He had known it was there, he said later, but still it came as a surprise. There it was; three and a half miles of deserted crescent, curving eastward, the blue-gray waters of the Channel on the left, the white waves rolling up onto the stretch of smooth sand. “What’s this gun here?” the boy said, the car was parked now on the rise behind the two concrete emplacements. The boy had run around to the front of the first of them, and was looking at the long, rusting barrel that pointed down the beach.

“That’s an old 88,” Rudder said. “You can see how it was set here to cover the beach.”

“I wish we could go in this blockhouse,” the boy said, “but there’s this screen over the front of it.”

“You can see they had direct hits from the Navy on it,” his father said, “but they never could get that gun. That’s why the soldiers had to come in and take it,” The boy had run now to the second emplacement, and his father walked after him. The father was wearing black shoes, gray sharkskin trousers. a reddish plaid shirt, a mixed-tan

“You can get in, and there’s a big machine gun here, that was covering the beach, too,” the father said and then he swept his hand below, “And right over there is where Frank Corder got hit. They were trying to make it up here.”

Frank Corder was a young captain from Rock Springs, Texas, who had joined the Rangers late, Rudder had hand-picked the Second Ranger Battalion at Camp Forrest, Tennessee, in July of 1943, The battalion had shipped to England in December of that year, and it was a month later, when he was in Northern Ireland recruiting volunteers to be used as a reserve after the invasion, that he signed up Corder, whom he had met before. After the war, he and Corder went into the general appliance and tire business in Brady. Now Corder has three children and is a livestock dealer. “He lost his left eye and some of his teeth on this beach,” Rudder said. “He still gets some pain, on and off, but I’ll never forget one day I was trying to take him on a livestock deal, the way you will, and be squinted at me and he said ‘Colonel, remember this. I’ve still got one good eye,’ ”

Where the sand ends at the top of the beach the white, smooth, egg-shaped stones begin. There used to be about 50 feet of them, but now the French have built a six-foot, sloping concrete and fieldstone sea wall that covers most of them. On top of the sea wall there is a curbed sidewalk, and a two-lane roadway that runs the length of the beach for the convenience of sight-seers.

“What’s this?” the boy said. “A gas mask?” They had walked along the sidewalk and then down one of the flights of stairs leading to the beach. They had crossed the stones and Rudder was just standing, looking east along the sand, when the boy ran up to him with the olive-drab rubber facepiece in his hand.

“An old American gas mask,” Rudder said turning it over in his hands. “The old canister gas mask. I didn’t think you’d find anything here.” He turned now, and started to walk slowly back toward the two concrete gun emplacements, Then he stopped, and with the toe of his right shoe he started to scuff into the smooth, tight sand, “Can you imagine,” he said, “some poor American kid trying to find cover in this?”

“It sure is pretty now, with the waves and everything,” the boy said. “You’d never think there was any fighting here,” The late-morning sun had finally started to eat through the haze, and you could begin to feel its warmth. It was quiet on the deserted beach. with just the soft rhythmic slur of the waves and the Occasional cry of a wheeling gull.

“I want you to try to picture this. Bud,” Rudder said, turning again to look along the length of the beach and sweeping it with his right arm, “A lot of American boys died here.”

“Yes, sir,” the boy said.

“You’ve got to picture this whole beach covered with all kinds of equipment, with boats and trucks and jeeps and tanks, a lot of them wrecked, and with American soldiers, and the Germans firing into them from the high ground and a smoke haze over everything.”

Rudder paused, and then said to the boy,”You remember General Cota, Bud?”

“Yes, sir.”

Major General Norman D. Cota, of Philadelphia, was assistant commander of the 29th Infantry Division and took the 116th Regiment into Omaha on the right flank of the 1st Infantry Division. Later he became commander of the 28th Infantry Division. and Rudder led the 109th Regiment, under Cota, through the Bulge and on to Germany.

“Here’s where he did his good work, getting the boys up off the beach,” Rudder said. “A lot of them just froze from the horror of it, and he got them up.”

“Is he the one gave me that toy watch?” the boy said.

“His wife gave it to you.”

“I remember.”

They walked along the beach together, not saying anything, the boy swinging the mask at his side and watching the white waves slush up on the sand. Then the father turned back toward the smooth white stones at the foot of the sea wall and the boy followed him. When Rudder reached the stones he kneeled down. With one hand he began to pore among them, to the smaller stones underneath. “Here,” he said, handing three or four to the boy. “Put these in your pocket.”

War Souvenirs for Corder’s Children

The boy, kneeling beside his father, took the stones and looked at them. Then he looked at his father. “Why take them back to Buddy and Mary Glen?” he said, speaking of Corder’s children.

“These stones are off the beach where their daddy was hit, they might want them.”

We left the beach and drove back through Vierville and then turned right and followed the black top coastal road west toward Grandcamp-les-Bains. Looking down from the crest of the road we recognized the town at once, the red-tiled roofs that many an American Navy man will remember when he thinks of the little fishing and bathing community of a couple of hundred houses that stood, by a miracle of war, almost untouched between Omaha Beach and Utah Beach.

We drove through the narrow, cobblestoned street, to the rectangular quay west of the town. In the basin below the quay the black-bodied fishing boats, side by side, were rising slowly with the tide, and on some of them nets were drying, strung from their masts and booms. On the quay, a half-dozen fishermen were standing, and they turned and looked at us when we drove up and stopped the car, “But it is not necessary to go by boat,” one of them said, when I told them what we wanted to do.

“I know,” I said.

“It is very easy to go with your car,” he said, standing there on the quay in the sunlight and pointing. “You drive here through the village and five kilometers on the left you will see the road.”

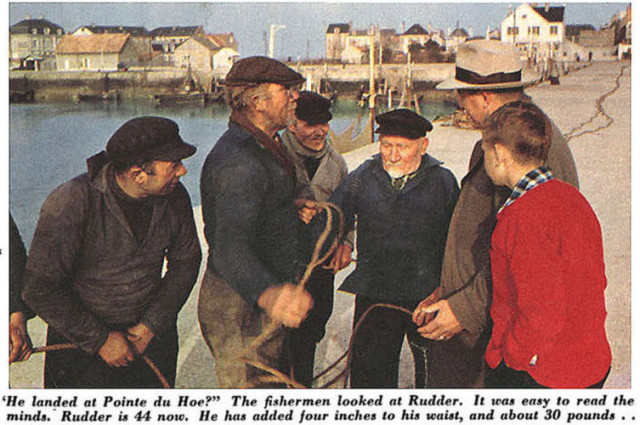

“But you do not understand,” I said. “The day of the invasion, this gentleman, here, was a colonel of the American Rangers. He was the first American to land at Pointe du Hoc.”

“He landed at Pointe du Hoc?”

“Yes.”

“He mounted the cliff?”

“Yes.” They looked at one another and then at Rudder. It was easy to read their minds. Rudder is forty-four years old now, his brown hair is graying at the temples. He has added four inches around the waist and about 30 pounds, and he was standing now, his topcoat open, trying to understand some of this.

“It was very difficult and very dangerous what he did,”one of them said.

That is how we got the boat, an old, dirty-green, 20-foot launch with the engine in the middle only partly housed, and the oily water slopping in the pit. There were three Frenchmen in it — the old man with the week’s growth of gray beard who owns it and the two younger ones — and they sat in silence together near the tiller and when, now and then, we looked back at them they would smile and nod their heads.

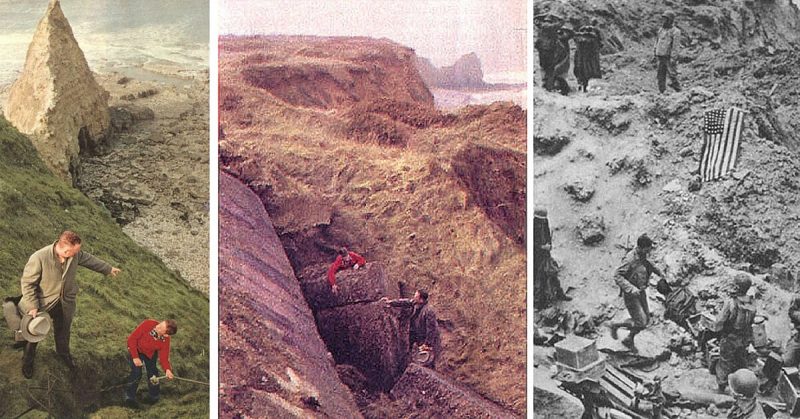

The sun was bright now, so the Channel was very blue around us, and when we had passed beyond the breakwater the old man turned east. Now we could see it unfold, the sharp nose sticking way out into the Channel and, beyond the nose, the dark cliffs rising 75 to 100 feet straight up from the narrow beach. “There it is.” Rudder said quietly, leaning with his elbows on the waist-high forward deck, with his son beside him. “Pointe du Hoc.”

He had heard of Pointe du Hoc for the first time five months before the invasion, in a second-floor room in London behind a whitestone front, with the blackout drapes drawn and four of them standing there with the maps and photos on the table. Rudder and Max Schneider, a colonel out of Iowa who had trained the First Ranger Battalion, had come up by train from Elude, in Cornwall, and they got their D-day assignment from Truman Thorson, the tall, thin-checked colonel out of Birmingham. Alabama, who was 0-3 for First Army, and from the officer who was Thorson’s assistant. “When we got a look at it,” Rudder said. “Max just whistled once through his teeth. He had a way of doing that. He’d made three landings already, but I was just a country boy coaching football a year and a half before. It would almost knock you out of your boots.”

The German Strong Point Had to Be Taken

The cliffs rise as high as a nine-story office building, from atop them Germans had observation of the whole channel and had mounted and were casemate guns capable of firing onto both Omaha and Utah Beaches. It was the Germans’ strongest point and it had to be taken. It was what General Omar N. Bradley was later to describe as the most difficult assignment he had ever given a soldier in his military career, Rudder and Schneider took the assignment back to Rude, put a 24-hour guard on the door and at night would get out the maps and the pictures and study them. Every time the Germans dug another trench or set another minefield the P-38 reconnaissance planes, skimming over the cliffs, got pictures of it.

The French brought back samples of the soil and the cliffs, and Rudder, in England, held the dirt in his hands and finally made the decision to scale the cliffs.

“Do you think we’ll be able to climb it?” the boy said now. The two of them, the father and the son, were leaning forward and studying the shaded face of the cliff. The old Frenchman was still taking the boat parallel to it about a quarter mile out, waiting for us to tell him to turn it in.

“No, son,” Rudder said. “We won’t.”

“But you climbed it before.”

“I was younger then, son, and we trained for it.

“We had the special equipment, too,” In the months before the invasion they had found, at Swanage, on the south coast of England, cliffs of almost exactly the same height and composition, and they climbed these, sometimes three times a day. They had ropes, affixed to steel grapnels to be propelled to the cliff top by rockets, and they also carried four-foot sections of tubular steel ladders and had mounted, on four DIJKWs, 100- foot extension ladders borrowed from the London Fire Department.

“It wasn’t a nice day like this, was it?” the boy said.

“it was a good deal colder and rougher,” his father said, “and early in the morning.”

Disasters of a Landing Operation

It had been 4:05 in the morning and still dark when the Rangers loaded into the British 1.CAs from the Amsterdam and the Ben Machree. They were 10 miles from shore and there were 225 of them and they had to start bailing with their helmets almost immediately. Twenty-one men from D Company had to he rescued by launch. One supply craft sank with only one survivor, and another threw its packs overboard to stay afloat.

“Can you imagine anybody going up that thing?” Rudder asked.

“It’s twice as high as I thought,” the boy said.

Lieutenant General Clarence R. Huebner, of New York. commanding the 1st Division and mounting the Omaha assault, had forbidden Rudder to lead the three companies of Rangers in.

“We’re not going to risk getting you knocked out in the first round,” Huebner had said.

“I’m sorry to have to disobey you, sir,” Rudder had replied. “but if I don’t take it, it may not go.”

Now the two younger Frenchmen moved forward quickly between us and. as the boat scraped down, they were in the water. They had on black knee-hoots and together they pulled the launch another couple of feet up onto the stones. Then they motioned, laughing, and one took the boy on his shoulders and the other took the father. And that is the way Rudder went in the second time, his topcoat open, his hat knocked back on his head and the Frenchmen staggering a little under the weight of the 230 pounds.

“This is what we hoped to land in,” Rudder said, looking down at the stony beach where the Frenchmen had deposited him, “but what we got was bomb holes and muck.”

The heavy bombers had plastered the cliff, and the near misses had torn the beach open. Most of the Rangers debarked up to their shoulders in mud and water. The DUKWs with the ladders foundered and were useless. Most of the rocket-propelled ropes were so heavy from the wetting that the grapnels failed to carry to the clifftop.

“Right here,” Rudder said, “is where Trevor touched down next to me. He was a British commando colonel, Travis H. Trevor, who volunteered to give us a hand and he just stepped out, right here, when a bullet hit his helmet and drove him to his knees, I helped him up and the blood was starting to trickle down his forehead, but he was a great big, black-haired son of a gun — one of those stanch Britishers — and he just looked up at the top of the cliff and he said: ‘The dirty *******.’ Fifteen men were lost on the narrow strip of stones. Some of the wounded crawled from the Crater line to the base of the cliff.

“Hey. Daddy!” the boy called. “Come here.”

Between two large boulders against the base of the cliff the boy had found a hollow shaft of rusted metal protruding from among the smaller stones. He had started to scoop the stones away with his hands, and now one of the Frenchmen got down on his knees and we watched him dig until, smile ing, he got up and handed it to us.

“A grapnel,” Rudder said, taking it. “One of the grapnels.”

There was the hollow shaft, about six inches long and an inch and a half in diameter, and then, at the head of it, the six bent prongs, petal-like. It was about the size and shape of a small boat anchor. As Rudder held it and turned it over, the rust flaked into his hands.

“This is amazing.” he said, shaking his head. “After ten years you can walk back here and find one of the grapnels on the ground.”

“Can we take it home?” the boy said.

“Certainty we’ll take it home,” Rudder said, “This must be the last of those grapnels.” He handed it to the Frenchman and pointed to the boat. The Frenchman nodded and ran to the boat and put it in. and now the boy was gone again and the father stood looking up at the top of the cliff, and the jagged dark line against the sky.

“Will you tell me how we did this?” he said. “Anybody would be a fool to try this. It was crazy then, and it’s crazy now,”

When the naval fire had lifted from the clifftop the Germans had conic out of their holes and trenches and concrete emplacements and, in addition to using small arms, they had dropped grenades on the heads of the Americans. In less than five minutes, however, the first Ranger had scaled the cliff, and within 30 minutes the whole force, minus casualties. had reached the top.

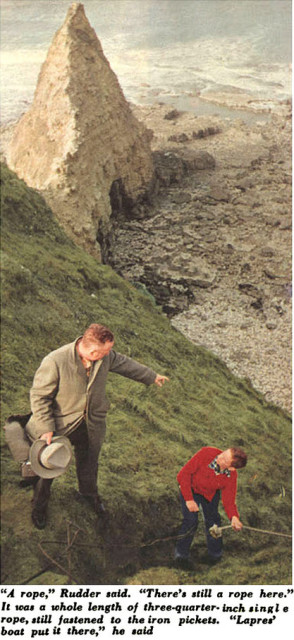

“M’sieur!” It was one of the two younger Frenchmen who had walked ahead of us, west along the small beach. He was standing now, calling and waving to us, close to where the nose of the point knifes into the Channel. “Regardez, M‘sieur!”

“A rope.” Rudder said. “There’s still a rope here.”

It was a whole length of three-quarter-inch single rope. It had taken on the mustard color of the clay that had washed down around it, and it hung there on the serpentine curve of the slope, still fastened to the iron pickets driven every ten feet into the cliff, its end flapping loose about six feet from the ground.

“Lapres’ boat put it there,” Rudder said.

Lieutenant Theodore E. Lapres, Jr., was from Philadelphia, and, about three weeks later, he lost a foot outside of Beaumont. just west of Cherbourg, Twice the rope had been cut that first day, and two men were hit getting it up there.

“M‘sieur?” the Frenchman said. He was pulling at the loose end and waving it as if to detach it, laughing at Rudder.

“No,” Rudder said, shaking his head.

“Can we climb it, Daddy?” asked the boy, who had run up to us now.

“No,” Rudder said, shaking his head.

“Why?”

“Because,” Rudder said, “we’re not going to get you hurt, son, on this cliff …”

Further Study of the Rusted Grapnel

On the way back to Grandcamp the sea was running with us, so it took us less than a half hour. Once, Rudder noticed the rusted grapnel lying on the floor of the launch and picked it up and looked at it closely again and shook his head. Then he put it carefully back on the floor of the boat.

“Grappin!” the same young Frenchman said, nodding, then he laughed and, with his hands and by shaking his body, he made the motions of climbing a rope. “A good souvenir.”

When we got back to the quay there was a small group waiting for us, a half-dozen fishermen and a thin dark-haired, middle-aged man from the Information Bureau of town. With him was a younger man, in his mid-thirties, and they wanted to know if they could show us the ground where the fighting had taken place at the top of the cliff.

“They can show us if they want to,” Rudder said smiling, “but I know it better than I know the palm my hand.”

The Rangers, fighting until relief could come up from Omaha, had been isolated on the cliff top for two days and two nights. About a half mile of flat, pastured tableland had spread back from the V edge of the cliff to the road that runs east and west between Vierville and Grandcamp, but when the Rangers had reached the top they found it an erupted wasteland of dirt and mud made unrecognizable by the heavy preparatory bombing from the air and the heavy shelling from the sea.

“Now you stay close to us, Bud,” Rudder said. “Don’t go running off.”

“I just want to see,” the boy said.

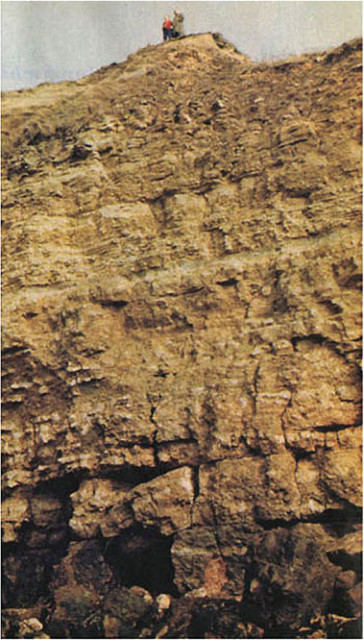

Rudder had parked the Peugeot on a small patch of level grass at the end of the hedgerowed lane that runs from the blacktop out toward the point of the cliff. We had started along a path between the shoulder-high growth of dark-green thorn bushes with the stalks of small, tight yellow flowers that the French call ajonc and the British call gorse.

“There wasn’t this growth here then,” Rudder said. “It was all just ripped-open dirt.”

The bomb and shell holes, one opening into another and some of them thirty feet across and ten feet deep, were grown with grass now, and Rudder picked a path between them. Then he came upon the concrete blockhouse, standing dome-roofed about eight feet above the ground, open toward the Channel, and its floor strewn with concrete rubble. He looked at it a moment, then called the boy.

“Bud,” he said, “come back here. I want you to see this.”

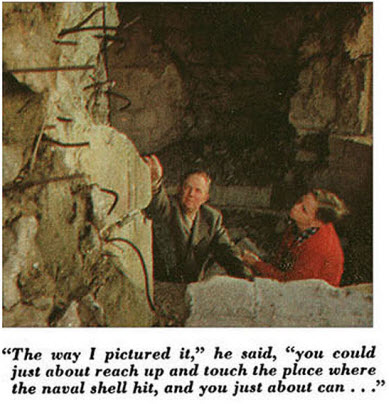

He walked down the two steps among the pieces of broken concrete, and the boy followed him. Then Rudder turned around.

Men Who Died at the Blockhouse

“This is where the shell hit,” he said, pointing up just above his head to a broken section of the corner where two rusted reinforcing rods protruded. “They say it wasn’t from one of our ships, but when you look at the direction, it had to be.

“The artillery captain,” he said, “a nice-looking, black-haired boy — I wish I could remember his name — was killed right here. The Navy lieutenant, who was spotting with us, fell right here.” He pointed. “It knocked me over right here.”

He pulled back the right sleeve of his topcoat, unbuttoned his shirt cuff, and exposed his forearm and the small red welt on it.

“Right under that,” Rudder said, “is a piece of the concrete from right here.”

“The colonel was wounded here?” the older of the two Frenchmen said.

“You carry it around in you for ten years,” Rudder said, “and you bring it right back where it came from.”

“I thought you had two pieces in there,” the boy said, looking at his father’s arm.

“I’ve thought about this a lot,” Rudder said. “I mean, you wonder how close it really was, if it was as close as it seemed and how a man could live. The way I pictured it, you could just about reach up and touch the place where the shell hit, and you just about can.”

The boy had found an old red-handled American toothbrush in the dust and broken concrete on the floor. He handed it to his father and his father looked at it and tossed it on the ground.

“Come around here with me,” he said to the boy.

They walked around to the east of the blockhouse. The shelling had ripped half the concrete off the side, exposing horizontal rows of reinforcing rods. Rudder climbed up onto the second one and the boy climbed up beside him, where they could both look toward the lane.

“Earlier that morning we were right here,” the father said. “The Navy lieutenant was on my right, where you are, the artillery captain was on my left and we were trying to direct fire over there when I got shot in the leg.”

“Where was the German?” the boy said, turning.

“I don’t know,” Rudder said.

The first time the boy had ever seen the bullet wound had been in the little house on South Bridge Street, sitting one night in the parlor. His grandmother was there and his uncle and his aunt and his sister and his two cousins. Someone had asked about the wound and his father had rolled up the left pant leg and there, just above the knee, was the pink scar where the bullet had gone in and, on the other side, the pink scar where it had come out. It had been a clean penetration, and so it had not looked like much of a wound to the boy.

“This way, Bud,” Rudder said now, calling again to the boy.

The boy had run ahead, running along the ridges between the bomb craters. There would be times when he would disappear completely in the growth, and then you would see his red corduroy jacket.

“I just want to see the CP,” the boy said, coming back out of breath.

“You’ll see it,” Rudder said. “Just be patient.”

“I think it’s over there,” the boy said, pointing over the rough ground and the green growth.

“You stick with me, son,” Rudder said, “and you won’t have to worry about where things are.”

“But I can find it,” the boy said.

“I’ll find it,” Rudder said. “I’ve been here before.”

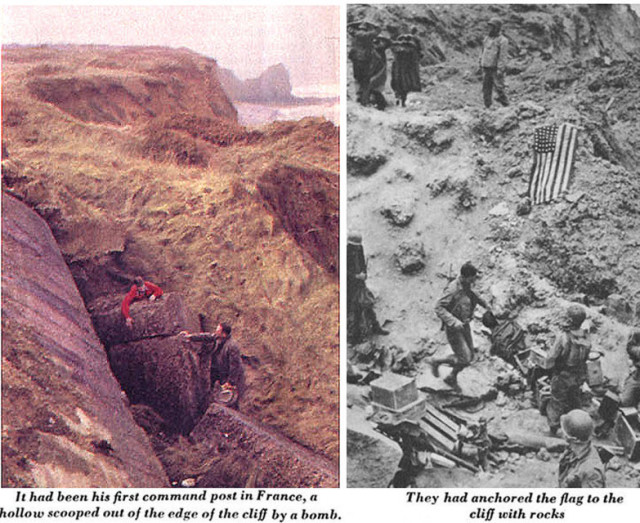

He walked as directly to it as you could, considering the turbulence of the ground. It had been his first command post in France, a hollow scooped out of the edge of the cliff by a bomb, and it was from here that he had sent out his first message: “Praise the Lord,” the code meaning: “Rangers up cliff.”

“Need ammunition and reinforcements,” he had sent out later. “Many casualties.”

“No reinforcements available,” was the answer that had come back.

Now he stood in the middle of it, and the boy was at the edge, peering down where his father had once ropeclimbed, down the sheer drop of about ninety feet, with the narrow stony beach below.

“Bud!”

“Yes?”

“Look, son. I want you to keep away from that edge.”

“I’m just looking.”

“You could fall off there, and I’d have to go home and face your mother.”

“Is that where our flag was?” the boy said.

“No,” Rudder said, pointing. “It was right over here.” They had anchored the American flag to the cliff with rocks. When the relief had come on D plus two the tankers had presumed that the Rangers had been annihilated, and so they had started to fire onto the point. He had waved the flag on a stick and the firing had stopped, and now the flag is in the wooden box in the den of the white limestone house in Brady.

Along with the flag are the two German revolvers, the two German chrome-plated 2-mm shells, the two German knives, the French beret and the D.S.C., the Silver Star, the Bronze Star with cluster, the Purple Heart with cluster, the Croix de Guerre, and the Legion d’Honneur.

“Mommy finally got a box with a glass in front and put the medals in it and hung it on the wall,” the boy had said one night. “Then it fell off the wall and broke to pieces, and after Mommy went to all that trouble Daddy just laughed.”

Rudder climbed up now on one side of the scooped earth. He walked around to the side of the buried blockhouse.

The Freckle-Faced Little Prisoner

“We got our first German prisoner right here,” he said. “He was a little freckle-faced kid who looked like an American, and we were so proud of him, because when you’re trying to get your first prisoner, it’s like diving for pearls.

“Then I had a feeling there were more of them, and I told the Rangers to lead this kid ahead of them. They just started him around this corner when the Germans opened up out of the entrance and he fell dead, right here, face down with his hands still clasped on the top of his head.”

“How many were in there?” the boy said.

“We killed one and got seven or eight out,” Rudder said. “It was right here, too, that we left the artillery captain, lying right here on a litter when we took off on D plus two.”

“We can go down in here,” the boy said, calling up from down inside the entrance. “It’s open and we might find something in here.”

“He was only about twenty-five years old,” Rudder said. “I’m sorry I’ve forgotten his name.”

We walked back to the car and drove out the lane that leads off the point and then down another lane where Leonard G. Lomell, of Toms River, New Jersey, then a sergeant and later commissioned in the field, and Staff Sergeant Jack E. Kuhn, of Altoona, Pennsylvania, had found the big guns, hidden behind a hedgerow and set up to fire onto Utah Beach. The Americans had bashed in the sights and had blown the recoil mechanisms and the barrels with thermite grenades.

Now you could still see the gun pits dug into the drainage ditch along the hedgerow, almost covered with creeping vines. We walked down the green lane and then walked left along another hedgerow and then down across a hundred yards of field that, in season, would be a field of wheat.

“I want you to picture this, son,” Rudder said.

The field was covered with a lush green, ankle-high growth of winter rye and clover. At the foot of the field was a mortared stone wall, about eighteen inches thick and four feet high.

“This is where Sergeant Petty had his squad, Bud,” Rudder said, stopping where a rough opening still gaped in the top of the wall. “From here they could look right down into this valley.”

“Was there any fighting here?” the boy said.

“There was a lot of fighting here, son,” Rudder said. “That first night the Germans attacked right through that orchard there, and got around behind Petty, who was way out here.”

An Eager Candidate for the Rangers

Sergeant William Petty had come from Cohutta, Georgia. He was a pale-faced, unimposing kid with slide blond hair and no upper teeth, and he kept coming to Rudder during the heat of that summer of ’43 in Tennessee. Rudder had turned him down twice and then, when he had gone over to screen the 80th Division volunteers, Petty was in the front line.

“I thought I discouraged you, Petty,” Rudder had said.

“Please sir,” Petty had said. “I’ll look better when I get my teeth.”

“All right,” Rudder had said. “If you want the Rangers that bad, I’ll take you.”

Petty was made a Browning automatic rifleman. “When he got up to platoon sergeant he asked Rudder if he could still carry the heavy BAR. He carried it up the cliff and killed, they figured afterward, about thirty Germans with it, and there are many among the Rangers who today still say that Petty saved their lives.

“These were brave men, here,” Rudder said now to the

The boy had thrown his leg over the wall and was looking at the hole that Petty and his men had knocked into the top of the wall to give them a better field of fire for the BAR. He nodded his head.

“You have to remember, son, that it was pitch dark and they didn’t know how many Germans there were or where they were.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You remember how you used to feel when you had to go to the henhouse at night at the ranch?”

“Yes, sir.”

Rudder turned around and looked back up the slope of the green field. With the toe of his right shoe he made a pass at the rye and clover.

“If I had this kind of cover at home,” he said, “I’d sure put some sheep on it.”

He finished with his piece of ground. It was late afternoon and we drove back, through that crossroad outside Formigny and east to Bayeux. That night we sat in the small linoleumed lobby of the Lion d’Or waiting for the BBC news on the small radio standing on the radiator cover. The boy had gone up to bed.

“You wonder so long,” Rudder said, “what it would be like to come back. Then you come back and it’s hard to know what you feel.”

We were alone in the lobby except for the woman in the black dress leaning on the desk with her elbows and watching us and then turning her eyes down when we happened to look at her.

“It was hard to believe when it was going on,” Rudder said. “It’s even harder to believe now.”

When Rudder had come back from the war he had lost himself in his family and his work. There were the two children before he went to war—the boy and Margaret Ann, who is now twelve—and three after the war—Linda, who is seven, Jane, five, and Robert, born last April. There is the office at the Brady Aviation Plant of the Intercontinental Manufacturing Company, Inc., where he is vice president. He is on the State Democratic Committee and the State Board of Welfare, and for six years was mayor of Brady.

“You think of the wonderful kids you had with you,” he said. “You think that if you could have men like that around you in a peacetime world, men as devoted as that, there wouldn’t be anything you couldn’t accomplish.”

“What about Bud?” I said, after a while. “What do you suppose he thinks of all this?”

“It’s hard to say,” Rudder said. “I kinda hope he’ll think a lot about it in years to come.”

I thought of the younger of the two Frenchmen from Grandcamp, watching the boy on the top of the point. The Frenchman had been unable to understand what the boy or his father was saying, but he was able to comprehend it, nevertheless.

“The father, he tries to explain to the boy,” the Frenchman had said, “but the boy, he looks for souvenirs.”

“Yes,” I had said. “He was four years old at the time of the war.”

“It is like it was with me,” the Frenchman had said. “When I was young my father would tell me about his war, the war of ’14. I could not understand. Then came the war of ’40 and ’44. After that I understood war. I understood my war, and I understood the war of my father.”

The next morning we had breakfast in the new hotel in Carentan, where, right next to the bar, there is a frosted wall light with the Screaming Eagle patch of the 101st Airborne painted on it. We had lunch in Saint-Lô, that was dust ten years ago and against which, ten years ago, we measured all destruction from then on. That afternoon we drove south and then, finally, east toward Paris through the winding, climbing country of the Falaise gap, where the Americans and the British had slaughtered most of what was left of the German Army that had tried to hold Normandy. It was about midafternoon, and we had just passed through Argentan, when the boy spoke up from the backseat.

“What did we do with the grapnel, Daddy?” he asked.

“I’m afraid,” his father said, “that we forgot it. We left it in the boat.”

“But we were going to take it home,” the boy said, “for a souvenir.”

“I’m sorry, son,” his father said, “but we just forgot it.”

I thought about the grapnel, lying in the bottom of the boat. We had paid the old man well for his boat and so, I supposed, he would leave it there for a while, thinking that we might still come back. Then one day, I imagined, he would be hurrying forward to check his lines or to catch the engine before it coughed out, and his foot or his pant leg would become entangled in the grapnel. Then he would stop and pick it up and look at it and think of us. Finally he would shrug his shoulders and then, taking a last look at it, he would drop it overboard. The sun would be shining, as I imagined it, and the grapnel would sink through the blue waters to the bottom of the English Channel.

It was the last of the grapnels and it had taken ten years for it to find its place, so that would be the end of it all.