Amid the chaos and perilous landscapes of German-occupied France, one remarkable woman emerged as a symbol of unwavering courage and indomitable spirit during World War II: Nancy Wake. As a Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent, she infiltrated enemy lines, becoming one of the most decorated female agents of the conflict. Known as “the white mouse,” she played a pivotal role in the fight against Germany.

Nancy Wake’s early life

Nancy Wake was born on August 30, 1912 in New Zealand. Her parents and siblings moved to Australia when she was only two, where she attended school until she was 16. She decided to run away to become a nurse. Rather than stay in Australia, she traveled to New York City, followed by London, where she went on to work as a journalist.

It was while in this position that Wake watched the rise of the new German government in the 1930s. She was working in Paris, reporting on European news, and saw firsthand the way Jewish people, in particular, were being treated.

In 1939, Wake married Henri Edmond Fiocca and the two moved to Marseille, France. They were living there when the Germans invaded during the early stages of the Second World War.

Joining the Pat O’Leary Line

Nancy Wake served in uniform as an ambulance driver before France fell to the Germans. When it did, she continued to fight for her new home by joining the Pat O’Leary Line, one of the country’s many Resistance organizations. They evacuated Allied airmen who were shot down to Marseille, where Wake lived. From there, the pilots were shepherded to Spain, then Gibraltar and, finally, back to the United Kingdom.

The Pat O’Leary Line operated very successfully for some time, although the job was made infinitely more difficult by the German occupation of Vichy France. Nonetheless, Wake was credited with saving hundreds of Allied men in the three years she worked with the Resistance, helping them navigate the route from France into Spain.

In 1943, the Germans were made aware of Wake’s role and sought to capture her, putting a five million Franc bounty on her head. The Germans were unsuccessful in capturing her, giving Wake the nickname “la souris blanche” – or “the white mouse” – for how easily she evaded them.

Traveling to the United Kingdom

Nancy Wake decided it would be best to flee the country, making her way to the UK. She followed the same route into Spain that she’d used for the Allied soldiers and airmen. Wake was briefly captured while in Toulouse, but was bailed out by the head of the Pat O’Leary Line. He made up a story that she was his mistress, trying to keep their affair from her husband. It worked, and Wake was able to escape the country.

Her husband stayed behind and was tragically captured by the Gestapo, who tortured him for information on his wife. When he refused to give it up, he was executed. Wake didn’t find out about this until the war was over.

Work as a Special Operations Executive (SOE) operative

When Nancy Wake arrived in England, she was accepted for SOE agent training. Reports from this time were very complimentary – even Vera Atkins, a high-ranking female agent, said Wake was “a real Australian bombshell. Tremendous vitality, flashing eyes. Everything she did, she did well.” Other reports said she “put the men to shame by her cheerful spirit and strength of character.”

After completing her training, Wake was sent back to France, along with a group of other agents, to help coordinate Resistance fighters in advance of D-Day. Her main role was to organize parachute drops for arms and other equipment in the Auvergne region.

After the successful Allied invasion, Wake’s role changed and she was involved in combat against German troops fighting in the area. She recalled one of her more impressive feats, traveling over 300 miles on a bike and by foot to get a message to another SOE operative.

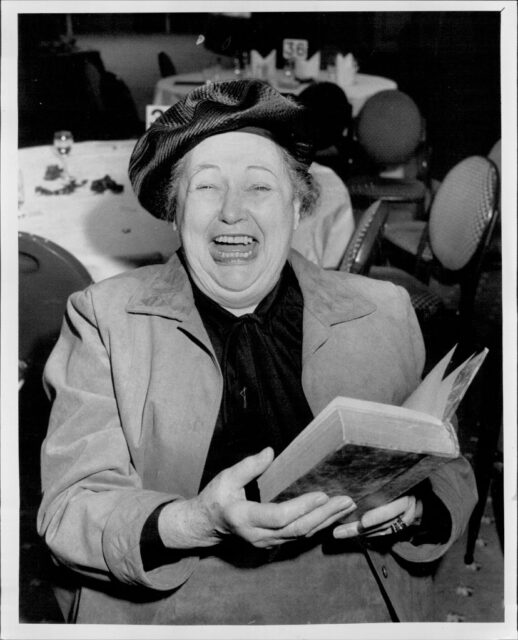

Nancy Wake had a colorful personality

Supposedly, Nancy Wake also killed an SS guard during a raid in a surprising way. She once said in a TV interview, “They’d taught this judo-chop stuff with the flat of the hand at SOE, and I practiced away at it. But this was the only time I used it – whack – and it killed him all right.”

Safe to say, Wake was an extravagant figure, as remembered by those who served alongside her in the SOE and the Resistance. On one occasion, her parachute got stuck in a tree, prompting another member to proclaim his hope that all trees bear such beautiful fruit. Her response? “Don’t give me that French s**t.”

Maj. John Farmer, in charge of Wake’s Resistance circuit, noted her uncanny ability to drink her comrades under the table on more than one occasion, saying, “I had never seen anyone drink like that.” Another SOE agent remembered her as “the most feminine woman I know until the fighting starts. Then she is like five men.”

After finding out her husband was dead, Wake declared, “In my opinion, the only good German was a dead German, and the deader, the better. I killed a lot of Germans, and I am only sorry I didn’t kill more.”

Nancy Wake’s life after World War II

When World War II came to an end, Nancy returned home, where she grieved the loss of her husband, blaming herself. In the years that followed, she became one of the most decorated women to have fought for the Allies. She was given the New Zealand Badge in Gold, the British George Medal, the French Croix de Guerre with two Palms and a Star, and the American Medal of Freedom with Bronze Palm, to name a few.

The only medal Wake refused was the Companion of the Order of Australia because she felt her country hadn’t appreciated her war efforts enough. In response, she told them to “stick their medals where the monkey stuck his nuts.” She eventually changed her tune and accepted the award. Wake made the decision to sell every medal she was given, as “there was no point in keeping them, I’ll probably go to h**l and they’d melt anyway.”

More from us: USS California (BB-44): The Battleship That Survived Pearl Harbor and a Kamikaze Strike

This legendary war hero died on August 7, 2011, at the age of 98.